News

Looking back over 120 years of Zionism

MILTON SHAIN

Since the Six Day War the term Zionism has been mangled and abused and increasingly employed as a term of opprobrium. Yet its meaning is simple: the national liberation of the Jewish people in their historic homeland.

Within that framework debates have raged – a socialist utopia; a negation of the Diaspora; a bi-national state; both sides of the Jordan; post-Zionism and so forth. But the origins of Zionism as a movement are now quite clear. Nineteenth century emancipation had failed the Jews.

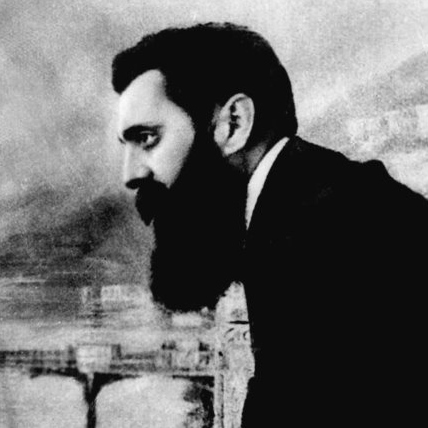

This was evident at the time Theodor Herzl convened the First World Zionist conference in Basel 120 years ago. By then medieval religious hatreds – rooted in Christianity – had mutated into secular forms of anti-Semitism.

Blood libels in central Europe, pogroms in Russia, the Dreyfus Affair in France, and race baiting in Germany and Austria, demonstrated Jewish vulnerability. Burgeoning nationalism, social Darwinism and scientific racism, reinforced the notion that Jews were immutably alien and rootless: a people apart.

Opponents of the Zionist idea believed atavistic hatreds would dissipate. Zionists, on the other hand, envisaged survival in terms of “auto-emancipation”, as Leo Pinsker put it.

Importantly, they wished to normalise the Jewish condition. Theirs was not a religious response, but rather a product of secularisation in the 19th century. Religious Jews for the most part abhorred the movement and only gradually came on board.

From the start, Arabs resented Jewish resettlement in Palestine, then under the Ottomans. Most refused to recognise the 1917 Balfour Declaration that promised Jews a National Home within British Mandate Palestine, and subsequently Arab leaders failed to reach a modus vivendi with their Zionist counterparts.

For Europe’s Jews, however, options were narrowing. Massacres in the Ukraine and the rise of Nazism threatened Jews, while exclusionary policies adopted by the “New World” (including South Africa) foreclosed emigration possibilities. Zionist ideologues had read the intellectual and political mood correctly.

In the wake of the Second World War and the destruction of European Jewry, a United Nations Special Commission on Palestine, recommended partition. During the UN vote in November 1947, those in favour knew they were supporting the creation of a Jewish state alongside an Arab/Palestinian state. It was both a reasonable and moral option.

While the Holocaust may have partly motivated some voting members, the idea of partition predated the mass killing of Europe’s Jews. It complied, moreover, with regnant notions of national self-determination. And Jews were considered a people in the national sense.

Zionist leaders accepted the UN decision. Today it is often forgotten that the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence did not determine that Israel was to be a Jewish state, but rather that the newly-created Jewish State was to be called Israel.

Hebrew would be the official language and the state’s symbols and public life Jewish in character.

Notwithstanding successive wars and a huge influx of poor – mainly Mizrachi – immigrants, as well as being in a festering if not explosive neighbourhood which for the most part has refused to recognise the Jewish State, Israel has survived and flourished.

Even Israel’s critics – those who frame the conflict between Jews and Arabs/Palestinians within the colonial settler paradigm, making much of the “second-class” status of Arab Israelis, or who question the possibility of a “Jewish State” being democratic – ought to acknowledge that Israel compares favourably with the “family of nations”.

To be sure, the Jewish character of Israel does not contradict the norms of democratic governance. A nation’s symbols need not be neutral as evident in the flags of many countries that bear the sign of the cross or the crescent. Furthermore, the adoption of a state religion is no exception. After all, apart from Lebanon, all Arab countries, have adopted Islam as a state religion.

Nor is the contentious “Law of Return” – seen by Israel’s critics as privileging Jews – unique. Many countries have similar legislation which favours national diasporas.

But only Israel is assailed in this regard.

When it comes to the treatment of its minority Arab population (within the Green Line), Israel is not perfect; but much has been corrected. Importantly the treatment of Arab Israelis compares favourably with the treatment of minorities in other liberal democracies.

States are never neutral. Turkey, for example, will always be identified with the Turkish language, its culture and its national identity. Put simply, Israel is not exceptional. Her less than perfect treatment of Israeli Arabs is certainly comparable to the treatment of minorities in many other respected countries.

Few know, for example, that Israel has a lower infant mortality rate among its minorities than France, Britain and other European countries.

The bottom line is that Israel’s Declaration of Independence declares all its citizens equal, without distinction of race. Activists (of whom there are many in Israel) highlight shortcomings and abuses.

Similar shortcomings and ambiguities exist in many other democracies. Israel is not alone. But the excoriation of Israel in world forums is unique.

Perhaps a withdrawal from the territories occupied in the Six Day War will lower the temperature. This is far from certain. The choices for Israel are not easy. But its vibrant democracy ensures dynamic engagement on all issues, including theocratic overreach, the gap between rich and poor, and even post-Zionism as an ideology. The Zionist forefathers would have expected nothing less.

Milton Shain is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Historical Studies and a former director of the Isaac and Jessie Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Cape Town.