News

Proving one’s Lithuanian ancestry means access to an EU passport

MOIRA SCHNEIDER

While there are professional services one can utilise, Seeff chose to go through the process himself. However, he says, he won’t repeat the experience when he tries to get Lithuanian passports for the rest of his family as it was difficult.

“First of all, you need a lot of information from the department of home affairs that is often not easy to get hold of. The Lithuanian authorities are very specific in what they want – if you get it wrong, they just reject your application quickly.”

There is an application fee, as well as costs for translating documents into Lithuanian. Seeff estimates that taking on the process himself cost about R3 000, whereas using the services of a Lithuania-based agent could have cost him anything from about R15 000 for the first applicant, plus a further R8 000 per additional family member, along with a family success fee of R15 000 once citizenship had been granted.

An agent will research the archives in Lithuania to find the necessary documents, says Seeff. “The agent I know will only take on the case if she can find the documents – she won’t charge a fee and then say she can’t find any documents.”

He says there are no guarantees. Even if you have the right documents, the Lithuanian authorities could still reject the application.

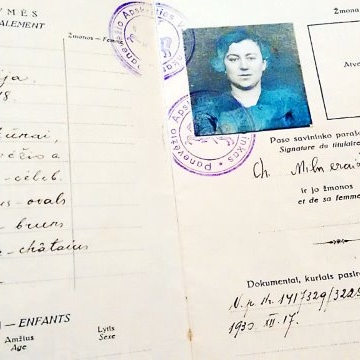

The starting point – being the reinstatement of citizenship – is that one’s ancestor has to qualify in terms of Lithuanian legislation, says Seeff. “In other words, they had to have been a Lithuanian citizen between the years 1918 and 1940 (the years during which it was a sovereign nation, not under Polish or Soviet control). So, they had to have been born there and lived in the country during those years.

“The best start would be a birth certificate. If you were born in Lithuania in 1900 and came to this country in 1914, then bad luck to you.”

There is, however, a “new hiccup” that was ruled on in a Lithuanian court case late last year. “If your ancestor did qualify by being born between those years, but took up South African citizenship before 1940, then you are disqualified because they would have had dual citizenship, which was not allowed.

“So, now you have to prove that your ancestor did not take up South African citizenship. If they did so after 1940, it wouldn’t be a problem.”

The case is being appealed, but currently the law stands.

Once you’re over the first hurdle of establishing citizenship, you have to prove your link to the individual concerned, says Seeff. “If your grandfather’s name was Chaim, for instance, and he was born in 1920, came to South Africa and didn’t take up citizenship, you have to prove how you are related to him.

“If his name on his birth certificate is Chaim and in South Africa it shows that his name was Hymie, you have to then prove that Hymie and Chaim are the same person. This can be hard to do. You’ll need an affidavit from the Yiddish authorities in Lithuania stating that Hymie is the English equivalent of Chaim.

“That’s where it helps to have an agent in Lithuania. If you’re lucky, on your South African naturalisation papers it will sometimes say: ‘Hymie, previously known as Chaim.’ In that case, you’re fine.

“After this you have to get your birth certificate, which will show who your father is. And then you have to get his birth certificate to show that his father was Chaim or Hymie, and prove the link along the way.

“If you’re going through the maternal side, you have to have marriage certificates to show the change of surname.”

All the documents have to be translated into Lithuanian by an official translator, and everything has to be certified as original by the home affairs department. The process is known as apostille.

Seeff estimates that working through an agent, the process should take a year.

A Johannesburg migration lawyer says he has come across a “sizeable minority of applicants who have been wrongly advised”. Sometimes applications have not been put together correctly, resulting in wasted costs or indefinite delays.

In one instance, he says, a family paid almost R15 000 to obtain archival records from Lithuania, when the process is, in fact, relatively simple and much cheaper to effect.

He cites another example of a client who unsuccessfully (and at great cost) used the services of an agency with no real knowledge of Lithuania’s legislation, but still offering Lithuanian citizenship application services.

“There have been instances where applicants have received unofficial letters congratulating them on becoming Lithuanian citizens, with no official proof of their applications having been successful,” says the lawyer.

“Unfortunately, these situations play out repeatedly and the best advice to applicants is: be cautious and make sufficient enquiries before embarking on the application process.”

Martynas Taujanskas, of the Lithuanian Embassy, concurs that the first thing to prove is that you’re the descendant of a Lithuanian citizen. “If you’re able to prove that your father, grandfather or great-grandfather was a Lithuanian citizen, then you would be eligible.”

If you’re unable to prove this, you can go to the Lithuanian archives and apply for the relevant documents. “Quite a few people don’t know that,” says Martynas Taujanskas. “They have 99% of the documents, going back centuries. If you meet the requirements, you become a citizen.”

The embassy reviews documents and then sends them to the migration department in Lithuania. Similarly, individuals can mail their documents directly to this department or work through agents in Lithuania.

While the reinstatement of one’s citizenship is the route most South Africans of Lithuanian extraction choose, there are other channels to obtaining Lithuanian citizenship.

Applications worldwide began in 1990, when Lithuanian independence was restored.

If individuals decide to apply for citizenship at the embassy, the consular fee is €50 (charged in rand, according to the exchange rate) for processing the documents. For documents couriered directly to the migration department in Lithuania, the cost is €41.

Should people choose to go to an intermediary, such as a lawyer or a company, to help with the application, the embassy will not interfere in the case of a dispute. “It’s a private contract between them and the intermediary,” he says. “We cannot recommend any intermediaries, translators or private enterprises.”

The bottom line is this, says Taujanskas: “If you meet the requirements, you become a citizen. If you don’t, you won’t.”

A complete list of the documents required appears on the embassy’s website. Log on to za.mfa.lt

Herb Klein

February 21, 2018 at 11:48 am

‘Thank you for your interesting article. My journey towards getting Lithuanian citizenship is a long one. Through the Montreal Jewish Geneological Society which I joined I met and spoke to world expert on most of these sorts of fields of study a Mr. Stanley Diamond. Further I consulted with Lithuania expert Howard Margol (now deceased). My father who was born in Lithuania in 1906 would have had to get what is called an external passport in order to be allowed to leave the country. This document was issued after the government was satisfied that the applicant had no criminal record or unpaid debts and had done whatever military duty was required.

Now it seems that between 1919 and 1940 the Lithuanian government of that time did not permit dual citizenship so if an immigrant was granted citizenship of his adopted country he automatically lost his birthright of Lithuanian citizenship.

In my current application I included my father’s British naturalization documents. Archive copy from Kew in London. Most of the names of Lithuanians changed when they were translated from the Yiddish. So not an exact match with the archive in Vilnius. An official archive document spelling out the name change history confirmed the data.

The man at the Pretoria Embassy refused to provide information or details of the Lithuanian government policy saying that it was not his job. He referred me to the application form and was impatient for me to leave.

So where does this leave applicants? It seems to me that Lithuania is reluctant to grant such citizenship rights. 95% of Jews in Lithuania who might have wanted to emigrate after 1940 were dead. I speculate that Lithuania is afraid that the descendants of those few Jews who left before the horrors may want to file applications for compensation of assets seized from those relatives who didn’t make it. Poland was recently faced with a similar situation.

I am told there is to be an election in Lithuania in 2019 and this citizenship issue may be tackled by aspirant politicians. Maybe finally then I can have success with my application for an EU passport.’

Ian

October 25, 2018 at 7:35 pm

‘Hi, thank you for this great article. My grand father was born in Lithuania in 1922 and I am trying to get Lithuanian citizenship. Could you please provide me the contact information of the agent you have been working with?

Thank you for your help,

Ian’

Aubrey Friedman

February 26, 2019 at 11:12 am

‘I am looking at getting a Lithuanian citizenship,I have the relevant documentation. Please advise who to contact ‘

Mandy

August 6, 2019 at 3:30 am

‘I am also looking for a contact based on my ancestry’