News

On Yom Hashoah, remembering her father

MIRAH LANGER

That’s the line of yours that has been swirling around in my head again and again the last few weeks.

This April 2018, with what seems the astonishing amount of 37 years of life behind me now; this Yom Hashoah, more than a decade and a half after you shuffled off this mortal coil: I remember you.

I am almost entirely the last person on this planet who does so, but I do. And it matters.

After all, I am, as psychotherapist Dina Vardi termed it, your “memorial candle”. The child born after the Holocaust to a survivor who then bestows upon them the responsibility, the duty, the weight of the past.

As I grow up, it is to me, and really only to me, that you begin to speak, over and over; always trying to find a way to finish; always needing to start again.

I was far too young for you to impose that upon; that’s the truth. And I am eternally grateful that you did; that, too, is the truth.

I spent my whole life trying to figure out what to do with your story, how to finish it off when you could not – until I began to realise that that was never the point.

There is no end to the Holocaust experience. It exists in spite of time and out of it. It transforms, and transmutes: sometimes pulling us in, sometimes pushing us away; it remains malleable to meaning, open to engagement.

And so this Yom Hashoah, the story I choose to tell is of bravery.

There is no particular reason why you, my grandmother and aunt survived when others didn’t. There was nothing more noble or lovable or powerful in any of you that enabled you to live.

What does emerge, though, is that when it became clear that you were alive, then you made choices so fierce, and bold and courageous, that it is a little heart-breaking.

Oumi, my grandmother: I think about how she gets you out of Austria after the Anschluss; leaves her husband behind at a train station; extracts, out of what seems thin air, false German passports through which you are reborn without a yellow star; how she convinces the priests at a Roman Catholic school to take you and your sister in as their own.

And then how, for her, all of this is simply not enough…

Instead, after fighting for this safety, she chooses to endanger her children’s lives all over again; opening up her house to save in hiding whoever and however many she can.

Is more valiant humanitarianism possible?

I jump decades later.

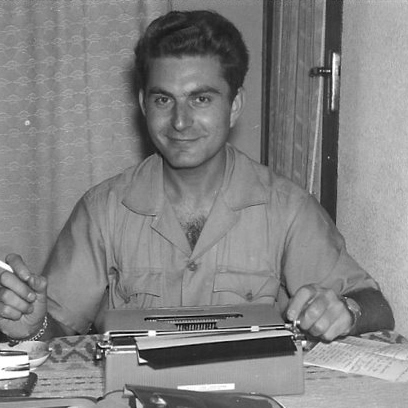

I think about your decision to become my father. Already behind you, you have an unfinished education, wasted talent, an abortive career, a previous failed marriage and a lost son – and then here you are at aged 49, willing to try again, to love again.

Now, as your story bleeds into mine, I begin to ruminate on who it is that I have become: A teacher at a Jewish school, working with 16 to 18-year-olds.

It is exactly the kind of school denied to you, and it is exactly students of the age that most represents the years stolen from you; students of the age that also defines the one time in my life which you, since you had no experience of it, made so impossibly difficult for me.

In between my students and my trying not to make each other crazy with the huge pressures and everyday irritations of being a classroom clan, I have such love for them.

They win your heart, my students – with the sweetness, the bittersweetness, of their youth; with the intensity with which they approach everything, unable yet to arrange a hierarchy of what is truly important – but mostly, mostly, with the endless scope and astounding angles of the questions that they keep throwing at the world – slowly coming to terms with the reality that the answers will not always instantly boomerang back.

This generation, in their own way, are so fiercely brave.

And so here today, as I sit here at my computer, in the last patches of muted autumn sunlight, all this tangles and tussles inside of me.