News

Dutch resistance – a tale of dedication and deception

MIRAH LANGER

“To avoid being easily caught, [a] method was not to dress American crewmen up as peasants or farmers… but to dress them up as senior German army officers,” said Jos Scharrer at a recent talk on the Dutch resistance at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre in Parktown, Johannesburg.

“There is a simple reason for that. German soldiers were in awe of authority, so if a German officer stomped into a room, a normal German soldier would never tackle him, he would give a Nazi salute, and answer, ‘Yes, sir, no, sir’,” Scharrer said.

“As such, these American airmen were trained to walk around like German officers, with arrogant, insolent expressions, and they were given some basic German phrases, like ‘bitte’, ‘danke’, ‘jawohl’ and ‘ja natürlich’.”

“Quite extraordinarily, it was a highly successful operation,” said Scharrer, adding that, “In a nutshell, the Dutch resistance did two things very well: first, it was supremely good at hiding people, second, it knew how to operate escape routes.”

It was Henri Scharrer, a French-speaking journalist living in Holland at the time of World War I and an expert in this particular escape scheme, who was the personal link which kindled Jos Scharrer’s interest in the Dutch resistance.

Born in 1900 in Belgium, Henri was Scharrer’s father-in-law. Indeed, his courageous exploits – and tragic ending – shaped the life of his wife and children, including Richard Scharrer to whom Jos was previously married.

“I must be honest… I often thought my husband’s stories were a bit over-the-top, and that he was inclined to exaggerate, but there was no exaggeration about these resistance stories. They were all far, far worse than I had realised.”

Scharrer’s mission to uncover Henri’s story culminated in the publication of her book, The Dutch Resistance Revealed: The Inside Story of Courage & Betrayal.

The title of the book highlights the complexities of the underground in Holland, which was heavily infiltrated by double-agents. “Henri’s fate tells us not just of the incredible heroism of the resistance, it also reveals how dangerous Holland was due to the high number of pro-German supporters and collaborators.”

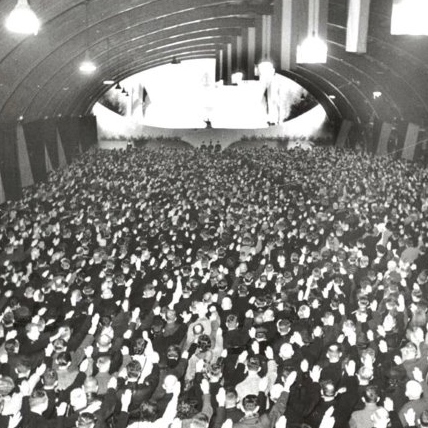

After all, Holland had a very strong pro-German sentiment. During the war, about 55 000 Dutch people joined the Waffen-SS, the Nazi’s armed wing, in Amsterdam. Furthermore, it is estimated that about 200 000 pro-Nazi Dutch assisted the Nazis in some manner. There was even an official group, the Henneicke Column, whose members were paid to report Jewish people in hiding. About 8 000 to 9 000 Jews were betrayed in this manner.

Yet, there were about 20 000 highly active Dutch resistance members. There are also estimates of between 60 000 to 200 000 ordinary Dutch people – including landlords, caretakers, and farmers – who assisted in hiding others, and helping those on the run.

Besides assisting the Allied crewmen to escape along various routes, “there were about 1 700 young Dutch people ‘Englandvaarders’ [English paddlers, as they were dubbed] who went on those escape routes and actually made it to London alive”.

Furthermore, many were helped in hiding. “They actually hid about 21 000 to 22 000 Jewish people in Amsterdam alone.”

21 Emmakade, Amstelveen, the ordinary brick house of the Scharrer family, would become one of these hiding places.

At the time of the German occupation of Holland on 10 May 1940, Scharrer had been working steadily as a political and economics journalist.

Yet, life soon became unsettled. Pockets of unrest broke out; new laws and regulations were implemented; and the small-scale rounding up of Jewish friends and neighbours culminated in the cordoning off of the Jewish quarter in Amsterdam, effectively turning it into a ghetto.

As a foreigner, Scharrer was fired from his job, and sent to Schoorl prison camp. He stayed there for five months. On his return, he committed himself to the resistance.

Scharrer become accomplished as a forger of exceptionally authentic-looking false documentation, as well as planning escape routes.

Yet, on 18 August 1944, Scharrer’s years of successful underground work were thwarted when he was arrested on a train after being found with two sets of papers on him. Once German officials realised that he was a key resistance fighter, they planned to use him as bait to nab his entire cell.

German collaborator William Pons was placed in jail with Scharrer. He managed to convince Scharrer that he was a fellow supporter, and that if Scharrer raised 9 000 guilders to pay an underground German agent, he could be released.

In his desperation, Scharrer wrote to his wife, Truus, asking her to arrange this sum.

On 29 August 1944, as she and three other resistance fighters gathered at a café to exchange the money with Pons – who had since been “released” from prison – they were ambushed and arrested.

Subsequently, Scharrer, and one of the other men who had been arrested, were moved to Vucht prison camp.

“On 6 September 1944, 300 prisoners [from Vucht, including Henri and his compatriot] were taken to the woods under armed guard. They were mowed down with machine guns.” Trucks were waiting. The bodies were loaded immediately, transported to crematoriums, and incinerated.

“They family never knew what happened; they just disappeared.”

Henri had been careful never to tell Truus specific information about the resistance and, as such, she was released after a few weeks. In the aftermath of Henri’s death, her sons recall that Truus was never the same, suffering from bouts of depression.

Scharrer’s death occurred in a country that had the highest per capita death rate of all the occupied territories.

In terms of the Jewish population, the statistics for Amsterdam reveal the stark tragedy. In 1941 in Amsterdam the Jewish population numbered 154 887 residents. In the 1954 census, between 23 000 and 24 000 Jewish people were documented as living in Amsterdam. “The reality lies in these horrific figures.”

Scharrer reflects on what many have said about the legacy of the Dutch Resistance: “Through the resistance’s work, its bravery, its courage, and the fact that so many lost their lives and were executed… the Dutch resistance saved the soul of the Dutch nation.”