News

Albania’s righteous Muslims testimony to the power of good

MIRAH LANGER

So generous was the care that the country showed to Jews in this dark period, it was essentially the only country in Europe that had more Jews after the war than before. This is what Gershman wants the world to know through his work.

Gershman’s views are contained in a documentary about his work screened at the opening of an exhibition of his photographs at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre in Parktown, Johannesburg, last week.

In it, Gershman expresses the urgency of his photographic project. “[The Albanian rescuers] risked everything, [yet] they are forgotten. If I get a remnant of a story, it has to live as a remnant of the goodness of people. We owe it to these people.”

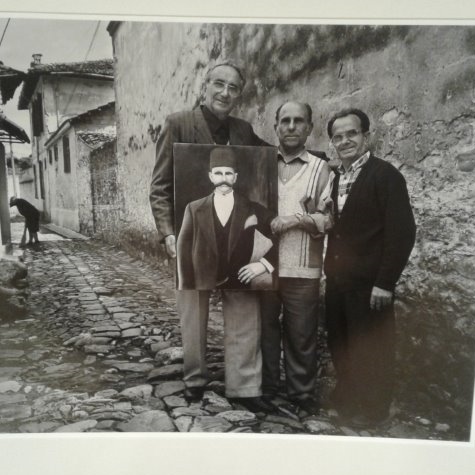

The exhibition consists of black and white photographs of various Albanians – mostly Muslim and some Christian – who themselves or through family members helped to rescue and protect Jewish people under the Nazi regime. The photographs have been supplied by Yad Vashem.

Prior to the screening, the holocaust centre’s education specialist, Rene Pozniak, gave context to the story of Albania during World War II.

By the time Hitler came to power, Albania had about 800 000 people – “only about 200 of whom were Jewish”.

Then, as Hitler tightened his grip across Europe, about 600 to 1 000 Jews sought refuge in Albania.

“What is remarkable is that the Albanian people defied the orders from Nazi Germany to give up lists of all [the country’s] Jews.”

Furthermore, it was not only ordinary Albanians who protected Jews. “There were even government agencies that gave false papers to Jews so that they could mingle and be protected”, said Pozniak.

“Albania was a beacon of light in a very dark continent.”

The exhibition and documentary are both titled Besa, which refers to a code of honour in Albania whereby a promise made becomes a righteous obligation for life and across generations.

Sadik Kalaja, one of the rescuers photographed, defines the code as an “order” he was taught by his father that “if there is a knock on the door, take responsibility”.

Brothers Hamid Veseli and Xhemal Veseli expand on the faith that led their parents to protect Jews: “Our parents were devout Muslims, and believed as we do that every knock on the door is a welcome from G-d.”

One of the rescuers photographed, Kujtim Chiveja, describes in her caption how her father, Qani, described it is a privilege to have helped Jews. “it gave him joy to put into practice his Islamic faith,” she says.

Other Albanian rescuers speak of hiding Jewish women behind traditionally Muslim veils, and forging passports to change their names to those which sounded more Islamic.

In the documentary accompanying the exhibition, Albanian Muslim Rexhep Hoxha explains how a pledge his father made to a Jewish family he sheltered during World War II became a Besa passed on for generations.

Hoxha describes how when he was a teenager, his father, Rifat, told him of a couple, Nissim and Sara Aladjem, as well as their small son, Aron, who had fled from Bulgaria to Albania, and were taken in by his family.

Hoxha’s grandfather, a Muslim cleric, and his wife, moved out of their room in order to house the Jewish family, who were total strangers the Hoxha family had found wandering the streets.

When the Aladjems decided to flee before the end of the war, as the Nazis tightened their grip on the main centres of Albania, they left behind three books in Hebrew and therefore indecipherable to the Hoxhas.

“They are beautiful and full of mystery,” muses Hoxha in the documentary. Sixty six years later, he holds them with reverence, and keeps them in a box he made in woodwork class as a teenager.

Nissim promised to return for them after liberation, fearing that if they were caught with them before then, their Jewish identity would be discovered.

“I am trusting you to keep them safe. Protect them as if they were your own eyes,” Hoxha’s father recalled Nissim telling him.

Hoxha said that his father regarded the promise as sacred. When Nissim and his family never returned and Hoxha’s father grew older, he passed on the Besa on to his son.

It is Hoxha’s journey to fulfil this promise that forms the core of the documentary. It led him to Israel to return the books – discovered to be Machzors for Pesach – to their rightful owner, Aron, now an elderly man with a son of his own.

Hoxha’s story is just one of the exceptional stories that are revealed behind Gershman’s portraits of ordinary heroism.

A Jewish survivor, Johanna Neumann, who speaks in the documentary, is at pains to remind the world how rare it was that even government officials, as well as the king of Albania at the time, King Zog I, actively refused to collaborate with the Nazis against Jews.

“Everyone knew we were Jews, and no-one ever made an issue of it or denounced us,” she says.

Gershman, too, lauds the choice made by the tiny country. “There was a collective agreement to save people while the rest of Europe was turning its back. This little country doing what it did – it has something to teach the world.

“It reminds us that there are far more good people in the world than bad people.”

Ultimately, declares Gershman, “What I have learned about Albania is that your greatest export is not fish; it is not metal, it is Besa.”

Gershman’s own mission, he says, “is to counter the paranoia about Islam that is dominating the West”.

“The common humanity that we all share is my battle, and I am fighting it with my camera,” he says.