News

Jozi’s tree-lined streets may look stark in future

JORDAN MOSHE

The polyphagous shot hole borer, or borer beetle, first garnered attention in 2008 after infesting avocado orchards in Israel, and was later found burrowing into millions of trees in California in the United States. Now facing the largest invasion by surface area to date, South Africa has come under attack and seems powerless to do anything about it.

But if radical action isn’t taken soon, walking down tree-lined streets in any of the big cities on Shabbos (or anytime) is going to be far less enjoyable as most of the trees may be gone.

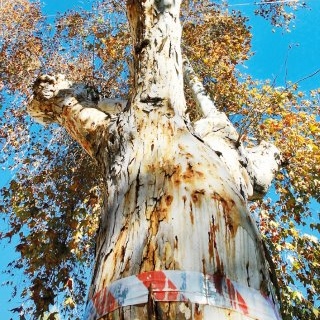

Johannesburg residents have in recent weeks taken to marking dead or dying trees with red paint or plastic ribbons, and created social media groups to discuss the issue.

Experts have said that at the current rate of infestation, the pest is likely to drastically reduce the green canopy of Johannesburg, with some tree experts saying that as much as 30% of all its trees could die. It could also affect the avocado, macadamia, wine, fruit and nut industries.

According to entomology expert Professor Marcus Byrne of the University of the Witwatersrand, the beetle was first spotted in South Africa in 2017 by Dr Trudy Paap in the KwaZulu-Natal National Botanical Garden in Pietermaritzburg. “She detected them during routine inspections of sentinel trees – exotic trees used for precisely the purpose of picking up alien pests entering South Africa,” he says.

Byrne explains that the insect is of South-East Asian origin, and since its detection has been found in Pietermaritzburg, Durban, Knysna, the Northern Cape, and Johannesburg (including Soweto). It is likely to be in many other urban centres by now.

Johannesburg has been hardest hit, however, as its avenues are lined with as many as 10 million primarily exotic trees, most of which were planted during the gold rush. The city also boasts numerous parks as well as countless large properties dotted with trees, creating a vibrant industry of gardeners, tree fellers, and tree surgeons.

Regarding the signs of infestation and its effects, Byrne says it depends on the species of tree. “Infestations on many tree species are obvious, as small sugar ‘volcanoes’, which are cones of sap, exude out of a tiny hole in the tree. Other trees just show damp spots that may have a hole associated with them. Other species sometimes have patches of sawdust-like material sticking out from the bark, which is the faeces of the beetle along with ground-up wood ejected from the tunnels that the beetle bores into the tree.”

As dire as the situation is, there are currently no solutions available. Byrne says no insecticides are registered for use against the beetle, and even if there were, applying them to a whole tree is a mammoth task that carries the serious side-effect of contamination of the rest of the environment around the tree.

He adds that, given that insects pollinate our food crops and trees turn carbon dioxide into oxygen, we shouldn’t contemplate spraying urban trees with poisons. “Drenching the poison into the tree’s root system, or injecting it into its tissue, also carries collateral effects to the environment,” he says. “Also, the beetle and its associated fungus (the real pest, as that is what makes the tree sick) are deep inside tiny tunnels in the wood of the tree. Getting an insecticide to penetrate into all of those tunnels is very ambitious and highly unlikely over the total surface area of a large tree.”

There are also no preventative measures that can be taken to guard against infestation, and all one can do at the moment is assess which tree species are infected or susceptible, and the extent of the problem. “We need to develop legislation to ban the movement of infested wood to prevent the spread of the problem,” says Byrne. “The infested wood must not be transported anywhere to avoid spreading the insect and its fungus. Destroying the tree might not be necessary, because the tree might be able to resist the attack on its own. Wait and see – and monitor the rest – is the best policy. Dead trees should be felled and chipped small, or burned on site.”

If no lasting solution is found, the worst outcome would be a profound change in the appearance and ambience of Johannesburg, and it could be worth considering planting more trees in the near future.

“Our 10 million trees provide shade and humidity, along with their obvious aesthetic features such as flowers and foliage,” says Byrne. “Forward planning by replanting with resistant, preferably indigenous trees in spots where susceptible trees are lost is worth considering already. We know species such as Chinese maple are very susceptible and likely to die, so they could have a replacement species growing in place.”

Byrne says the best outcome would be if a native parasitic insect adopts the beetle as a new host, bringing its numbers down to trivial levels. However, he says, it is more likely that South Africa will need to import a parasitic organism to combat the beetle, such as a tiny wasp, fly or worm that uses the beetle as its host.

“This type of biological control can be very successful and South Africa has a great deal of expertise in this field,” he says. “An alternative biocontrol agent could be a fungus that attacks the pest fungus. This line of defence is obviously the best option, but it will take time and money to do the research.”