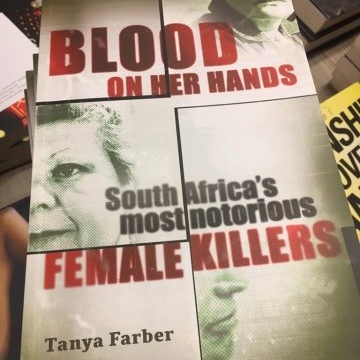

Featured Item

The fascination of the female serial killer

TALI FEINBERG

The book, Blood on Her Hands: South Africa’s Most Notorious Female Serial Killers, covers local women whose names have become famous: Dina Rodrigues, who murdered baby Jordan-Leigh Norton; Najwa Petersen who murdered her husband Taliep; and Phoenix Racing Cloud Theron, who killed her mother.

Then there are the ones we may not know so well, like Daisy de Melker, who killed her two husbands and children with poison in the 1930s; or Chane van Heerden, who butchered her victim in a way that plays out like a horror movie.

“My book features women who cannot on any level justify what they have done,” says Farber. “Someone said to me during the process that many women who kill do so for a good reason, and my response was that that isn’t always the case. I note in the book that I didn’t include women whose actions can be explained – like the mom who kills her tik-addicted son, or the desperate shack dweller who dumps her newborn baby in a bin. All the women in my book should be held entirely responsible for their crimes.”

The idea for the book surfaced when, as a science reporter at the Sunday Times, Farber read research on American serial killers, and what made women different from men. “From there, I wrote a newspaper feature, and it soon became clear that there was a whole book inside me,” she says.

She found it fascinating that generally speaking, women put a lot more effort into planning a murder than men, and their psychological makeup is far more interesting. “A lot of the research shows that women tend to kill for resources or for gain, and I speak about that a lot in the final chapter of the book, which is the insights and analysis chapter. Women are also more likely to have accomplices or to hire hit men. I think people are also more fascinated by them because of how statistically unusual they are, and because they subvert our stereotypical notions of women as nurturers who are more caring, and less prone to violent behaviour.”

Farber did not interview the women or their families, rather, it was a careful process of reconstructing the narrative of each story from written sources. “This included countless media reports, historical records, long court records, and affidavits not in the public domain. I did not, however, want it to be a dry account or for it to be written in a journalistic style. Instead, I would say it is narrative non-fiction in the sense that all the stories are true, but many parts of it are written using the same style that one would find in a novel. This was an amazing part of the process as it required climbing inside the mind of the “main character” in each story, and imagining what they might be thinking based on insights into their personality as it comes through in the records.”

Farber’s favourite story to write was the Daisy de Melker chapter. “It happened long enough ago for me not to be overwhelmed with sympathy for the people who died or whose lives were affected by the murders she committed. It was very interesting to look at South Africa’s history at that time, and imagine the world in which Daisy lived. Furthermore, of all the women in the book, she is the only one who worked alone and killed many people, and used poison as her weapon.

“By far the most harrowing was the Chane van Heerden chapter because of how she and her accomplice [her boyfriend] treated the body of their victim. Skinning, beheading, and dismembering a victim is a highly unusual crime, and writing that chapter gave me chills. It’s so hard to imagine someone wanting to do that to another human being, and yet, she had always been obsessed with skinning, and it felt as if she was born without a soul, in a sense.”

For her, the most difficult story to write was the chapter on Joey Haarhoff, who with Gert van Rooyen infamously kidnapped six girls in the 1980s. They killed themselves as the police closed in, taking the answers with them about what happened to those girls. “There were six victims, which meant that, in essence, six different stories had to be researched and written. They were all girls whose stories were written about so extensively in the mainstream media that doing the research was a painstaking experience,” says Farber.

“Also, I was a young girl of the same age as the victims in the late eighties when the crimes happened. I remember the absolute dread and fear of the time, and now, thirty years later, I am a mother of two girls who fall into the same age group as the victims and I cannot bear to think of what those parents went through. This was the chapter that literally gave me sleepless nights.”

Farber has recently begun to offer counselling services as a departure from her almost 20-years as a journalist, but the two are intertwined. “It was through my work as a journalist that I became aware of the huge need out there for counselling. There are so many people who need emotional support, but can’t necessarily afford private psychotherapy. I studied counselling, and have now set up my own after-hours service in which I do group counselling for people who are going through a similar issue or phase such as pregnancy, divorce, looking after an elderly parent, and so on.

“As a journalist, people tell me their stories, and it is important for me to be a good listener and to be highly empathetic. The three-year counselling programme has given me some extra tools to really hold someone in that moment when they are sharing a painful story with me.”

- “Blood on Her Hands: South Africa’s Most Notorious Female Serial Killers” is available at bookstores and on Amazon Kindle.