News

The link between Jews, magic, and mysticism

JORDAN MOSHE

To what extent does Judaism believe in magic? Do Jews hold by sorcery, and if we do, how does it work?

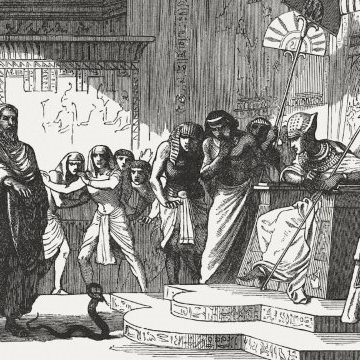

The Torah contains multiple mentions of sorcery, which seems to suggest a belief in magic. In Exodus, Moshe and Aharon perform extraordinary feats, and bring the ten plagues. Pharaoh’s magicians imitate some of these supernatural acts, transforming their staves into snakes, and summoning frogs.

Later, a number of verses in the Torah explicitly prohibit magic and sorcery: “You shall not allow a sorceress to live”; and “There shall not be found among you … a soothsayer, a diviner of times, one who interprets omens, or a sorcerer, or a charmer, or a necromancer. For whoever does these things is an abomination to G-d.”

The supernatural but divinely-powered actions of the Israelites are feted, but the magic of others (derived from a source beyond G-d) is disparaged. Many Torah authorities seem to believe that magic does in fact exist, and echo the negative sentiments expressed against practicing it. “He who practices magic will be harassed by magic,” wrote the third century sage, Levi, and the Sefer Chassidim warns that a “magician will come to no good”. Ramban agrees, saying that G-d created “spiritual” forces through which the natural world can be manipulated, but cautions that if one subverts the system by using this supernatural world, he is going against the will of G-d.

The rabbis in the Talmud echo the distinction, speaking against foreign magic which is not divine, but narrating stories of magical feats brought about by Torah learning and G-d. Talk of encounters with demons, reversing the flow of a river, and stopping houses from collapsing through supernatural powers occupy the narrative often. Consequently, Jews continued to be associated with magical practices by the broader world. In the Middle Ages, Christian beliefs about Jewish magic resulted in persecution. Called allies of Satan, Jews were charged with performing black magic, and it made them targets of the Inquisition. Certain Jewish customs, like washing hands upon returning from a cemetery, aroused suspicion and provoked violence, leading some to abandon certain religious practices and customs.

Some have suggested that this was the result of the Jewish propensity for science and medicine, areas often looked at with suspicion in the Medieval era. Jews were generally more effective medical practitioners because of their wide knowledge of languages, and their scientific arts made them superior “magicians” to some. The triumphs of Jewish medicine enhanced Jews’ reputation for sorcery, and though many non-Jews were known to call on these “sorcerers” to help them, some continued to treat them with suspicion and animosity.

The mysticism of the Kabbalah complicated this reality even further. Scholars have suggested that medieval Jews considered certain magical customs to be legitimate and embraced them because they were divine. The Kabbalah of the 13th century offered mystical values of Hebrew letters and esoteric formulae for coming closer to G-d, expressed through meditation and name-recitation – easily considered incantations and spells.

Another example derived from the Kabbalah and with roots in even earlier texts is a “Jewish amulet”. The Shulchan Aruch (code of Jewish law) rules that it is permitted to heal with an amulet, and to carry one for protection. Among the best-known amulets in our tradition is the mezuzah affixed to our doorposts, and the hamsa, a palm-shaped charm with an eye embedded in it. Like the red string you might have seen people wearing around their wrists, the latter was and continues to be used to ward off the ayin hara (evil eye), a superstition which claims that a person or supernatural being can harm a person by looking at them.

Jews have even been said to have a penchant for exorcism. The second century Christian scholar, Origen, credits us with a talent for exorcising demonic forces, and indeed, the first allusion to exorcism appears in the Tanach in the narratives of David. The Midrash outlines various procedures for expelling demons, and the famed Dead Sea Scrolls include several incantations, mostly for the banishment of disease-causing demons. Many exorcisms were public spectacles, often performed in a shul or requiring the presence of a minyan (prayer quorum).

Accounts and even videos of Jewish exorcisms continue to circulate today, and people said to be possessed by malevolent spirits still seek out personalities versed in mysticism to banish them. Other traditions of magic with which Jews have been associated continue to linger, though some in more modern manifestations.

Writer Ted Merwin says that it has been estimated that about 20% of American magicians are Jewish, including illusionist David Blaine. Others include Israeli mentalist Uri Geller, and even older examples like famed escapist Harry Houdini (born Erik Weisz, the son of a Hungarian rabbi), 19th-century French sleight-of-hand artist Alexander Herrmann, and the 20th-century Polish-American illusionist Max Malini (born Max Katz Breit), who performed for four different presidents at the White House.

Whether bringing plagues or escaping from boxes underwater, Jews continue to have an interesting relationship with magic. Distinguishing forbidden sorcery from esoteric religious practice has been a challenge throughout Jewish history, but ultimately, magic seems to have a place in our tradition and heritage.