Featured Item

Racism education ‘starts with parents’

JORDAN MOSHE

After choosing to broach the subject, Kirkel decided to share her experience with other parents grappling with the question of whether to discuss racism with their young children.

“White people in South Africa are scared to talk about racism, especially with our children,” she said in a webinar on Thursday last week. “It’s difficult, uncomfortable, and actually often deemed unnecessary. But we all know racism is very much alive in our country today, we’re just afraid to discuss it.”

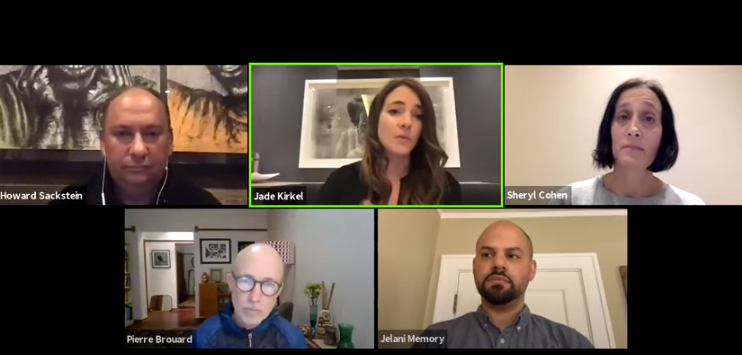

Psychologists, authors, and academics were among those who weighed in on the panel discussion chaired by Kirkel and Howard Sackstein, the chairperson of the SA Jewish Report.

“We’re coming to understand that it’s not enough to say that we don’t have a racist home, we actually have to teach our children consciously to be non-racist and to recognise the importance of race,” said Pierre Brouard, clinical psychologist and professor at the University of Pretoria.

“Race isn’t a biological truth but a sociological truth. However, to say to people of colour that race isn’t biological can be a form of gaslighting because we’re saying that their experiences aren’t real, when of course they are. It’s a real tension.”

Brouard believes that no one is born racist, that we learn about race through what we observe and what’s going on around us.

“As a species, we are wired to notice difference, and many parents will say that their kids talk about how other people look,” he said. “It’s what we do with that information about difference that makes a difference.”

Educational psychologist Sheryl Cohen agrees. “Children are born with a capacity to see difference, and this is absolutely normal,” she said. “In fact, it’s desirable. Talking about difference and race is as tricky for parents as not talking about it, but we need to raise the issue.”

Cohen said that the job of parents, adults, and educators was to help children to develop an integrated sense of self. “As children grow, they integrate an experience of good and bad,” she said. “We see children learn that people can be good and bad, and we aim to help them to develop an integrated sense of other and thereby develop an integrated sense of self. When they do that, they are developing a good model for growing up outside a racist perspective.”

Brouard said that key to addressing racism in children is to address racist attitudes in their parents, unconscious though they may be.

“I’m a product of apartheid, and though I consider myself ‘woke’ and I’m doing my own work around race, I can’t say I believe I don’t have a racist bone in my body,” he said. “It’s more important for me to say that because I was steeped in that system, I’m unconsciously racist at certain times, and my work is to undo that.

“Children learn racist ideas from their parents. People might think they aren’t racist, but if you participated in racial ideas in a particular way then I’d say you might be racist. Admitting it is the first step towards changing it.”

In his work, Brouard has often heard white people say that they are proudly colour-blind, and raise their children to be that way.

“My response to that is that you aren’t recognising the histories that people of different colours bring to their own story, histories of hurt, and histories of harm,” he said. “When you talk about colour blindness, what you’re saying is, ‘I don’t recognise those histories of discrimination that you or your people have experienced.’

“Colour is a reality. It’s a part of all our lives. It’s much more important to be colour sensitive in noticing difference without attributing negativity to those differences but seeing them as important.”

Admission by parents that they are slightly racist is an encouraging and important step, said Brouard.

“You can’t change something you can’t acknowledge,” he said. “That’s a lot of the work we have to do as white people: being able to say ‘yes, I have racism in me, and it’s something I’m working on’. We need to find opportunities where it can come to our awareness, and only then can we start to change.”

Jelani Memory, an American author of a children’s book about racism, and the founder of the A Kid’s Book About series, said his own experience with his children informed his approach to the subject.

The best advice he can give parents is to take the decision to talk about racism with their children.

“Just do it,” said Memory. “I can promise you that you won’t get everything right, you won’t cover everything, and won’t get it all done in one conversation. But the acknowledgement for all parents is to realise the likelihood that the biggest barrier between them and the kids’ learning is actually themselves.

“Muster up the courage to dive into the conversation, and know it’s just the first of many. Go on the journey with your kids, and learn with them. Plant the seed, and don’t wait until you are ‘graduate level’ to do it, because it may be too late.

“Decide to have the conversation, and find the tools along the way to do that.”

Memory said parents are afraid that opening the discussion will have an adverse effect on their children, encouraging racist attitudes.

“There’s an inherent fear that we will sully our kids, put them on the wrong track, or somehow teach them how to be racist. You’re not going to injure or derail your kid’s development when they’re five years old.

He concluded, “Be appropriate, pay attention to their developmental level, but don’t be afraid of breaking their innocence. We teach them not to hit, to share. Why not teach them another fundamental thing?”