Featured Item

Documents found in armchair show role of ‘ordinary Nazis’

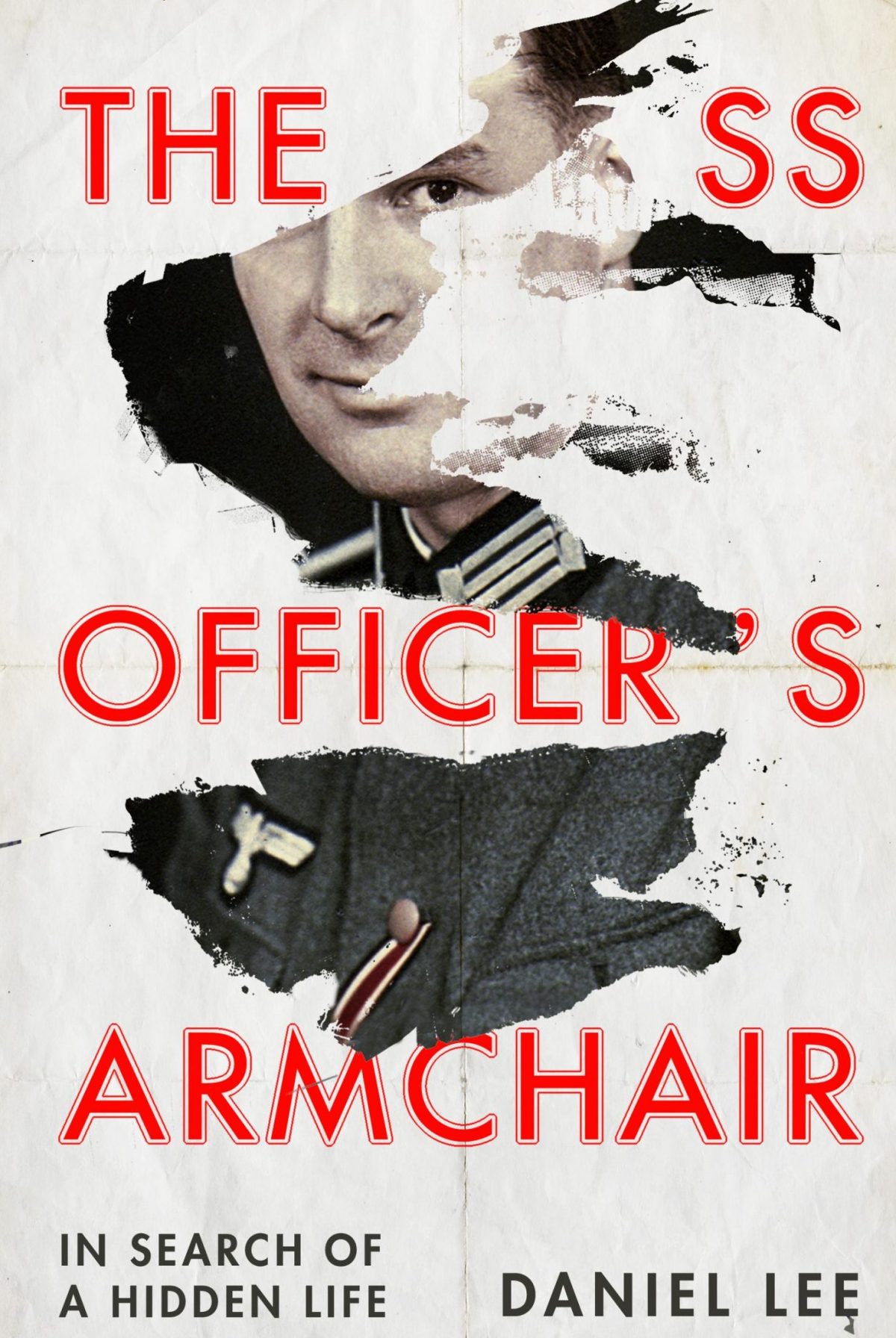

A new non-fiction book, described as a detective story and a thriller, explores the life and motivation of a low-ranking SS Nazi officer, whose name would never be known if his papers weren’t found hidden in the upholstery of an armchair decades after the Holocaust.

Dr Daniel Lee, the author of The SS Officer’s Armchair: In Search of a Hidden Life, spoke to Tali Nates, the director of the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre, in a webinar hosted by Limmud South Africa and the SA Jewish Report on the evening of Saturday, 22 August.

“We know about the so-called ‘desk killers’ [like Adolf Eichmann], the Einsatzgruppen [the mobile killing units who rounded up and shot Jews as the German army advanced east], and the camp commanders, but we don’t know many of the ‘ordinary Nazis’ whose names you might not find on Google, but who played just as an important part in the Final Solution,” said Nates in introducing the book, which centres on the previously unknown story of Dr Robert Griesinger.

An historian of World War II, Lee explained how the story “literally came out of the woodwork” when he was living in Florence. A stranger who became aware of his profession, asked for his help in finding out more about swastika-covered documents that her mother had discovered sewn into her old armchair when she took it to be re-upholstered.

The woman wasn’t a relative of Griesinger, and had bought the armchair many years previously. But when he began to find out more, Lee managed to find a number of Griesinger’s family members, who had no idea of their relative’s Nazi past.

Lee said Griesinger was ordinary in every way, and would have been lost to the annals of history had these documents not been discovered. “He was a typical SS member who came from a very middle class family, had a university education, and was Protestant. He ticked all the boxes of what an SS member should be.”

But when Lee dug deeper, he found that Griesinger didn’t have deep roots in Germany, but his family had lived in New Orleans in the deep south of America for a number of generations. With in-depth research that brought late family members to life, he demonstrates that Griesinger could have inherited his white-supremacist ideas from his grandmother, whom he adored, and who had grown up with enslaved people in her household.

The family returned to Germany only in the late 19th century, and Griesinger was born in Stuttgart in 1906, in the middle of the “war youth” generation that grew up with the defeat of Germany in World War I as a defining factor of their identity. “I managed to find his mother’s diary who wrote every day and collected photos and newspapers,” which showed how “this generation witnessed the absolute collapse of the values and certainties of their parents’ world.”

Lee traces how Griesinger went on to study law, eventually working as a public servant for the Gestapo in enforcing the Nazi state’s racist laws. “Griesinger’s work at the Gestapo rendered him a significant link in the chain of the Nazi police state,” he wrote. He worked in Stuttgart’s Gestapo “Hotel Silber”, where just a few floors below his feet, so-called enemies of the state were interrogated and tortured.

His career flourished as a lawyer and public servant. “He joined a group of lawyers who wore ordinary suits, not SS uniforms. He wasn’t going out and rounding up Jews, but he was responsible, and knew what was going on as he sat at his desk,” said Lee.

His career peaked at his posting in Prague in the ministry of economics and labour. “It was his dream come true to go to Prague. His kids went to the best schools, and they got the best rations. But his work put him in charge of Czech workers being sent to forced labour camps in terribly debilitating conditions. In 1943 in Prague, most Jews were incarcerated or sent to concentration camps. Of those that were still there, they were also sent to do forced labour under his auspices.”

How did the documents end up in the armchair? When Lee tracked down the late SS officer’s daughter, Barbara, she surmised that as a German in Prague in May 1945, he was under no illusion about the dangers he faced.

“Barbara described a scene in which a scared and frantic Robert, wanting to hide his identity papers, somehow opened the cushion and placed the documents inside,” he writes. He had reason to be frightened, as Lee looks into what his fate might have been at the end of the war.

Lee spoke about how he found that when Griesinger was newly married, he lived right next door to a Jewish couple, the Rothschilds. In the book, he recounts this Jewish couple’s astounding story, and finds their granddaughter, who says her grandparents would have lived a religious Jewish life – right across the wall from Griesinger’s home. Lee surmises that the couples probably interacted on a regular basis, and wonders how Griesinger separated this reality from his Nazi worldview. Mrs Rothschild, who survived the Holocaust, lived in London and “died in Wembley in 1983, the same part of London and in the same year in which I was born,” writes the author.

He recounted how he found another personal coincidence in his research. Although he tries to keep a personal distance from his work, he was startled to find that in July 1941, Griesinger’s Wehrmacht unit happened to pass through the shtetl that his maternal grandmother’s father came from in Ukraine. The SS officer had been called up to serve in August 1939. “For a fleeting moment in July 1941, Griesinger looked out on the district of Tarashcha, and experienced the same sights and sounds that for centuries had given familiarity to my ancestors’ everyday lives,” he writes.

The book also explores multiple issues arising from World War II and the Holocaust, such as the “wall of silence” that faced the next generation who asked questions about their parents’ role in those events. It examines the little-known fact that the Wehrmacht played a role in killing Jews, even though for decades after the war, historians and the German public believed it wasn’t involved in these mass murders. It questions our sometimes one-dimensional ideas of figures and organisations during that period.

In telling this story, Lee demonstrates that, “We still know far too little about how low-ranking officials experienced the 1930s and 1940s, and Griesinger’s life helps us to understand why Nazi rule was possible. Ordinary Nazis such as Robert Griesinger entered into loving personal relationships and made professional decisions to better themselves and their families. Men like Griesinger effortlessly switched from being kind, gentle, and funny to displaying cold-blooded cunning and indifference,” he writes.

Lee said that the research for the book took him five to six years. “I was never clear what I was after. There were so many threads and possibilities.” Indeed, the book spans way beyond Griesinger’s story, weaving in multiple fascinating narratives that demonstrate the impact one person’s life can have on the world.