OpEds

Can we bring the pandemic under control?

One and a half years into the COVID-19 pandemic may be a suitable time to look back, and try to visualise possible future scenarios. The world has experienced its most traumatic pandemic since the 1918/1919 influenza pandemic. As of 11 July, just more than four million individuals have reportedly succumbed to the virus globally, 187 million cases have been reported, about 10% of whom may go on to develop lasting symptoms, some with disabling consequences.

South Africa is experiencing its worst outbreak of COVID-19, driven by the rapidly spreading Delta (B.1.617.2) variant, low vaccine coverage, and also the winter season. In contrast, many high-income countries in the northern hemisphere are now starting to lift COVID-19 restrictions to gradually return to a pre-COVID-19 life.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the family of coronaviruses received relatively little attention from medical virologists. Two outbreaks of serious coronavirus disease, in 2003 and 2012, in the Far East and the Middle East respectively, were easily contained. When, in December 2019, an unusual cluster of pneumonia cases was reported in the city of Wuhan, China, it hardly merited much international attention.

The feeling was that this outbreak would go the same way as the previous two coronavirus outbreaks. However, the explosive global spread and uncanny property of the virus to mutate and generate numerous variants from the original ancestral strain took the scientific world by surprise.

The southern tip of the African continent lamentably had the added misfortune of being dominated by the most sinister of these variants, the Beta variant (501Y.v2/ B.1.351) – the “South African” variant. As a result, only two vaccines with evidence of satisfactory activity against the variant – the Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer vaccines – could be used in the country.

The unpredictable evolution of the virus continues to spawn new variants. The most recent variant of concern, the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant, has rapidly encircled the world, nearly displacing all other variants. Its contagiousness is estimated to be more than double that of the original ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain. Countries hitherto able to control the epidemic with extensive vaccination are now experiencing major upsurges. Fortunately, being more sensitive to vaccine-induced immunity, serious disease and hospitalisation has been reduced to only a fraction of previous rates.

Virologists remain puzzled by the virus’ ability to mutate so rapidly and acquire sinister properties so readily. In mid-2021, science still lacks the ability to predict the advent of new variants.

Effective COVID-19 vaccines have been developed at unprecedented speed, utilising new platforms. They have certainly shown their value in markedly reducing serious disease and hospitalisation, even though rates of milder infection are only modestly reduced. Similarly, virus transmission between people is also reduced but not eliminated, and the virus, particularly variants such as Delta, will still continue to circulate, even in highly vaccinated populations.

Will the next generation of COVID-19 vaccines provide greater effectiveness in not only reducing clinical cases but also preventing transmission? Extensive research into vaccines administered other than by injection, for example, by spraying into the nose, or taken orally, may not only be much easier and cheaper to administer, but could also provide more effective immune protection directly at the site where the virus enters into the body, and reduce transmission.

The novelty of the COVID-19 pandemic has also caught the sociological, behavioural, and communication sciences by surprise. Much still needs to be learnt. The crisis of a severe pandemic engenders in society a drive to search for explanations which may be beyond the rational. Comfort and reassurance may be sought in conspiracy theories or miracle cures. Blame is a common sociological response. There is an urgent need to develop more effective communication tools to instil responsibility in the risk takers, especially younger folk who may feel less vulnerable.

Mass immunisation of adults is another voyage in uncharted waters. Anxiety and suspicion of the new, rapidly developed COVID-19 vaccines has provided fertile ground for both a sizeable anti-vaccination lobby as well as an even larger vaccine-hesitant population. This is a further challenge to communication science.

So, what could a future scenario look like? Eradication? Control? Containment? Eradication of the SARS-CoV-2 virus isn’t a realistic possibility – only one virus has, as yet, been eradicated – smallpox. Regional elimination, as, for example, in the case of measles and polio, also seems unrealistic given the rapid global spread of the virus. Containment would appear to be the most realistic vision for the future.

The devastation SARS-CoV-2 has wrought on the world is consistent with it being a virgin-soil epidemic. In other words, a totally susceptible human host at the mercy of a virus introduced into the human population from a wild-animal reservoir.

Over the past one and a half years, population immunity has progressively built up from individuals recovering from infection (natural immunity), together with vaccine-induced immunity. While the threshold value for herd immunity can be calculated theoretically, the advent of new variants and the unreliable durability of immunity have confounded the ability to arrive at a precise figure.

What can be hoped for in a future scenario is a coronavirus behaving similarly to the four endemic coronaviruses which have long been in the human population. They cause mild upper respiratory infections such as the common cold every winter. In a future world, perhaps in a year or two, with COVID-19 no longer being a virgin-soil epidemic, SARS-CoV-2 could ultimately also become an endemic infection causing recurrent tolerable mild illness such as the common cold. In other words, it could become merely a fifth endemic coronavirus.

But, what of the threat of new viruses potentially being introduced from the wild-animal reservoir into humans and causing similar devastation? For this reason, scientific pursuit to understand how SARS-CoV-2 arose in China and then crossed the species barrier to establish itself so effectively in humans isn’t merely of scientific or political interest.

It’s also of great public-health importance to forestall a future COVID-19-type pandemic. It could provide direction to interrupt the pathway of transmission of exotic viruses from wild-animal reservoirs to humans.

If, indeed, it’s shown to have been a laboratory escape, it re-emphasises the imperative for greater biosecurity measures to prevent the escape of these dangerous organisms from laboratories.

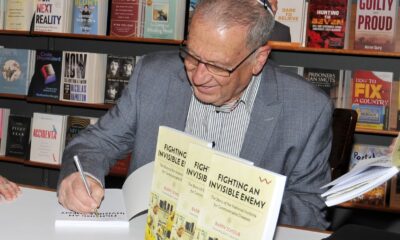

- Barry Schoub is professor emeritus of virology at the University of the Witwatersrand, and was the founding director of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases. He chairs the Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19 Vaccines. This article is written in his private capacity. He’s not a member of the health department, and receives no remuneration for his advisory services to the department. He reports no conflicts of interest.