Featured Item

The day Mandela came to shul

It was no ordinary shul brocha on the Shabbat when Nelson Mandela came to Marais Road Shul and had a cup of rooibos tea. Yet, beyond the charm of the event, it had profound resonance in shaping the connection between the iconic statesman and the South African Jewish community.

In honour of Mandela Day, Ann Harris, who was there with her late husband, the former South African Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris; former Israeli ambassador Dr Alon Liel; and David Gordon, the current president of the Green and Sea Point Hebrew Congregation, reminisced about the event with the SA Jewish Report.

On the first weekend after the democratic elections, Mandela decided to “pay his respects” to various places of worship, recalls Harris. On Friday, he went to mosque, and on Sunday, to a number of different churches, but Saturday was earmarked for a shul visit, and Marais Road was chosen because of its expansive size.

Congregants had never been more punctual than on that day, says Gordon. “I think, for the first time, everybody was there by 08:15 in the morning! Normally people stroll in five minutes before the brocha,” he laughs.

The atmosphere was exhilarating. “There were literally throngs of people out on the pavement waiting to come into shul. It was packed, and there was an absolute buzz in the air. People would keep going in and out all the time – everyone was checking – has he come yet? Has the car arrived? Everyone knew a little bit of news – ‘Now he’s on his way’; ‘He’s 10 minutes away’; ‘He’s five minutes away.’”

“We had davened, leined and finished the service when Mandela and his party arrived,” remembers Harris, telling how the shul congregants then cleared some of the area downstairs for Mandela and the group accompanying him.

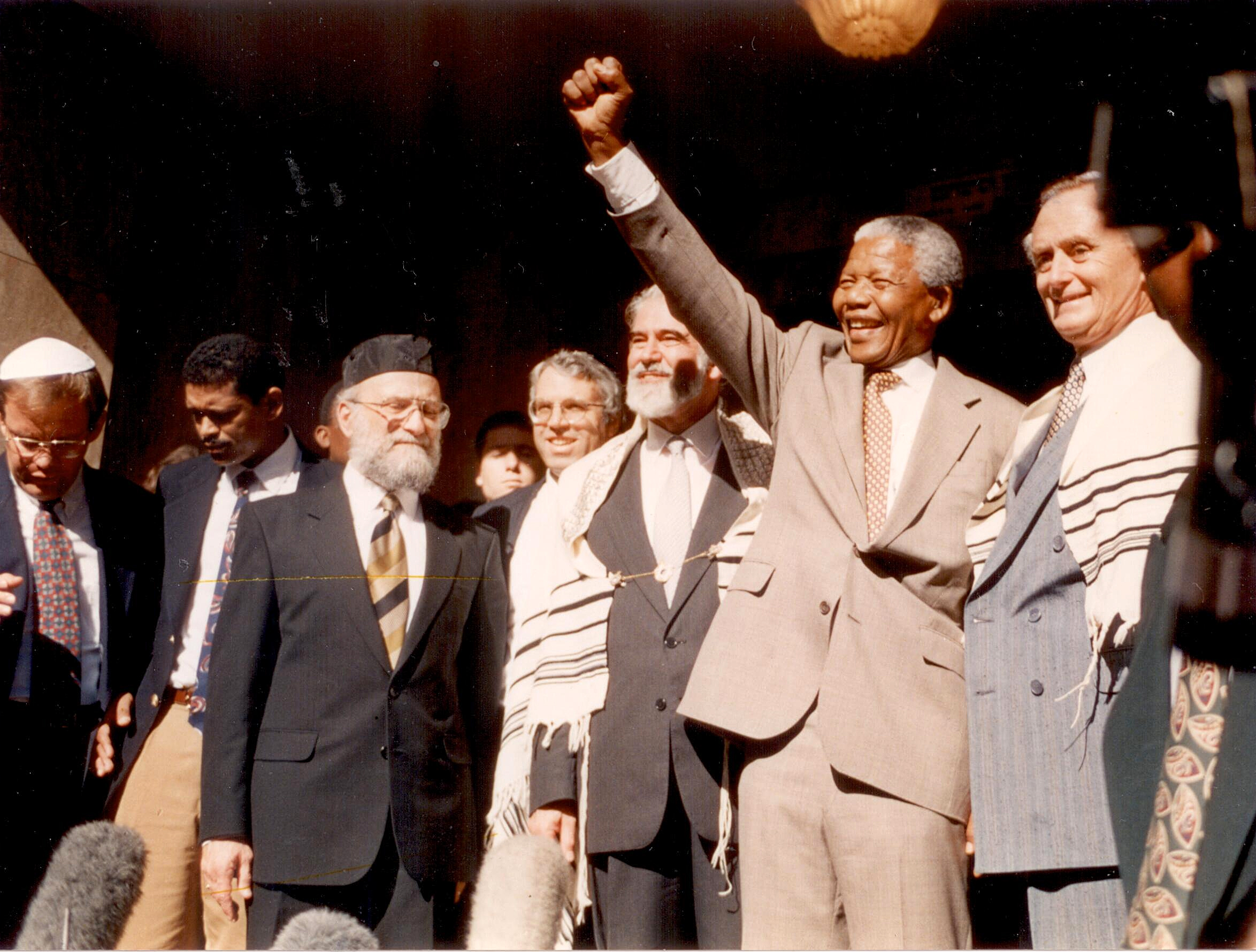

“He walked in with Chief Rabbi Harris, Rabbi Jack Steinhorn, Ambassador Liel, and Mervyn Smith, then the national chairperson of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies,” recalls Gordon. “Everyone stood and clapped. He was regal and exceptionally humble. He shook people’s hands and asked them how they were. He took his time, not rushing up to the pulpit. He acknowledged the people upstairs, and went to speak to elderly people in the front row.”

Various communal leaders gave speeches, and then Mandela began his address. “He opened by saying ‘Shabbat Shalom’,” which delighted the crowd, says Gordon.

Liel says during Mandela’s speech there was one moment that he – and the crowd – found particularly striking. “He was calling all the white people who had left South Africa for ideological reasons to come back to the country now that it was democratic.” However, Mandela added in a caveat, saying that this was “except for the Jews who had gone to Israel because they went to their homeland”.

“I was surprised he had such a sentence,” muses Liel. He later discovered that Mandela had taken up the suggestion of another community leader to add in this acknowledgement of the special relationship of the Jewish community across the two nations.

Liel recalls how after his speech, Mandela went outside to address the media gathered there. “He gave another short speech, and then he raised his fist.” It was a moment of political and diplomatic genius, he notes. “It was so clever of him to use his fist. It was the symbol of the struggle, and behind him was Cyril Harris, Smith, and myself. By doing so, he [essentially] recruited us to the struggle.”

Liel, who would later accompany Mandela on a visit to Israel, said that in every encounter with him, Mandela’s presence was that of a “giant of a man”.

Harris, remembers a distinctive moment during the time when the party stood outside the shul. “Mervyn Smith pointed out to him that we could even see Robben Island from the steps across the bay.”

The visit made headlines in Jewish publications overseas. At the time, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency quoted Smith as describing the event as the “peak in Jewry’s relationship with the new South Africa” and that “the determination of South Africans from all walks of life to make the transition work was never more manifest”. Smith, who died in 2014, played a key role in driving Jewish communal support of the country’s democratic project.

Gordon recalls that on the day of the visit, even after having taken all the obligatory media photographs, Mandela continued his stay by attending the brocha taking place, as usual, in the hall.

Ann Harris says she asked Mandela if she could get him anything to eat or drink, to which he replied, “I would love a cup of tea, but you know how I like my tea.” Indeed, she did, she says, adding, with a laugh, that it was a concoction she considered rather horrible. “Half a cup of milk with a rooibos tea bag stuck in, and then filled up with hot water. I mean, I quite like rooibos tea, but not like that!”

Central to any anecdotes from those who attended that day is Mandela’s personal interest in the people there, chatting to everyone from the cleaners to the rabbis.

Yet, Harris says, this was his usual modus operandi. “Even when he came to visit Afrika Tikkun [a non-profit organisation co-founded by the late chief rabbi], many times, you never knew where he was because he was so busy introducing himself, chatting to everyone, and talking to the children. You could never have a fixed programme because he wanted to meet everyone.”