Featured Item

Kyiv atrocities raise ghost of Babyn Yar

Imagine having your house blown up, civilians killed in your neighbourhood, and the organisation you work for attacked.

Russian soldiers made this the reality of the Ukrainian-based Ruslan Kavatsiuk, the deputy director of the recently attacked Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center in Kyiv.

“I learned yesterday evening that my house was blown up and burnt down with everything we own, including the car,” said Kavatsiuk on 30 March 2022.

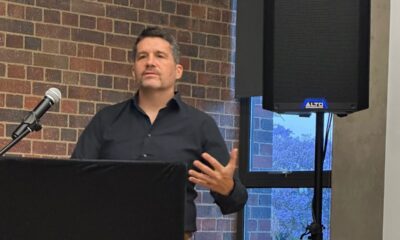

He was speaking at a webinar titled, “Voices from the front line: the relevance of Holocaust sites in the war against Ukraine”, organised by the Base and the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre.

“It’s clear that Russians cannot win this war militarily against armed forces in Ukraine,” said Kavatsiuk. “Now they attack civilians, like in my hometown, right next to Kyiv. Russians have killed many civilians. Civilians were killed in their cars. Sometimes only women were in the cars with children trying to leave the place of occupation.”

Kavatsiuk said Ukraine wasn’t very different to other countries in central Eastern Europe. “It’s a democratic country of 40 million people, and by territory, a little bit larger than France. Yet, our democratic country was attacked full scale by the Russian Federation.”

He said the last time Ukraine was bombarded this way was in World War II. “Right now, Russia is repeating that under a false, historical, so-to-say narrative that Ukrainians are some kind of Nazis and Russians are some kind of liberators of the free world and free people.”

All Holocaust institutions view this narrative as misleading and false, said Kavatsiuk.

The Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center has shifted from memorialisation and education to activism in the weeks since Ukraine was invaded. The same can be said for two Polish organisations – the Galicia Jewish Museum in Kraków and the Taube Centre for Jewish Life & Learning Foundation in Warsaw.

“We’ve seen crying people, we’ve seen tears, we’ve seen the emotions of our Ukrainian colleagues who had families back in Ukraine,” said Jakub Nowakowski, the director of the Galicia Jewish Museum, which has four Ukrainian employees, one of whom is fighting against the Russians.

“Because of those connections, those friends, those colleagues, it was natural that we needed to help them,” said Nowakowski. “We started helping their families. We started to do whatever we could right away, whether it was collecting medicine or food supplies. Colleagues of ours still have their families in Ukraine. We’ve been able to send those products and supplies directly to the people in need.”

On 28 March, the museum opened a day care centre run by Ukrainian refugees. “Since then, we’ve been bringing kids to the centre,” said Nowakowski. “They come from all of Ukraine and from very different backgrounds. Some come from cities, some come from villages, some have beautiful houses. All of them miss their fathers who are fighting. All of them miss their homes.”

Nowakowski emphasised the danger of being indifferent. “We just try to do whatever we can to help.”

For many decades, the Jews of Poland were on the receiving end of relief, said Helise Lieberman, the director of the Taube Centre for Jewish Life & Learning Foundation. “We’re now the ones responsible for giving. There has been a transformation, which we need to live up to. That includes how we educate, memorialise, incorporate, integrate, challenge narratives, make the world open up beyond the headlines and beyond those big letters at the top of your internet feed. What we’re seeing is that there’s evil and there’s good. We would all like to be in a place where we do good.”

After Russia invaded Ukraine, the Taube Centre quickly joined the Warsaw Jewish community to create a crisis-management team. It brought together all the Jewish organisations in Warsaw and tasked a group of people with responding as quickly as possible.

“We’re working with international organisations and our partners like Galicia Jewish Museum, and those in Warsaw and around the country,” said Lieberman. “We’re also supporting the JCC [Jewish Community Center], thinking of children’s programmes. We’re working to bring much-needed goods to places that aren’t near major cities. They have little access.”

The Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center is situated at the biggest mass grave of World War II. There, Nazi SS Squads carried out massacres in the early 1940s, beginning with the killing of more than 33 000 Jews in September 1941.

At some point thereafter, the site faded into oblivion. “The Soviet Union tried to erase the memory of Babyn Yar and the Jews who were killed there,” said Kavatsiuk. “It’s now a place of memory, of memory of about two and a half million Eastern European Jews who were killed.”

This summer, the centre planned to open the first museum in Babyn Yar. It would tell the story of the September 1941 massacre.

“Unfortunately, due to the attack in Kyiv, we have now had to suspend our plans to open that museum space,” said Kavatsiuk. “Some of the men in our team are now serving in the armed forces. Two of our historians were from Kharkiv. Their houses were blown up like mine. Now, one of them is in Germany, the other west of Ukraine. They continue their research, and we continue to research the names of the victims. We have established a humanitarian project to help Holocaust survivors, evacuate some of them, and help them with medicine, food, and water. In Kyiv in the area next to Babyn Yar, we established a programme to help disabled and elderly people.”