Featured Item

The remarkable life of Sergio Bergman

Sergio Bergman, a qualified scientist, became the first rabbi appointed as a government minister in Argentina. He is a close friend of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, better known to the world as Pope Francis.

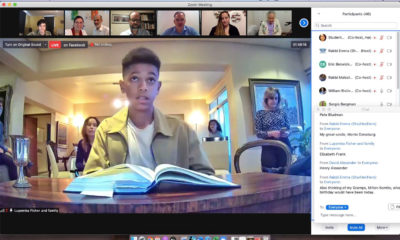

Rabbi Bergman, the president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ), was in Johannesburg as the guest of the South African Union for Progressive Judaism for its biennial conference, held over the weekend.

Bergman’s grandparents escaped the Holocaust, emigrating to Argentina in 1929 from Lodz in Poland. Bergman was born in Buenos Aires in 1962. He celebrated his Barmitzvah at the city’s Emanuel Reform Synagogue. Argentina, with about 250 000 Jews, houses the largest Jewish community in Latin America.

“We Jews are part of the Argentinian mosaic,” he said. “It’s a country built by emigrants who were welcomed from all over the world. We are a very creative and active community.”

But Argentina is a country of contrasts and contradictions, Bergman said. It offered refuge for Jews from war-torn Europe, but was also a safe haven for fleeing Nazis. “It’s a rich country full of poor people,” he said, endowed with natural resources but struggling to develop fully. “We need strong and active citizens, not just inhabitants.”

Bergman studied biochemistry and pharmacology, and worked in this field. “I loved my profession, but I had a vocation too. Something was calling me from when I was very young,” he said. He was a scientist by day and a student by night. He credits his wife, Gabriella, for encouraging him to pursue his rabbinical studies. He laughed as he explained how his father-in-law said that “becoming a rabbi isn’t a profession for a nice Jewish boy”.

“I went to Israel in the middle of the Gulf War in 1991,” Bergman said. “People told me I was crazy!” He studied at Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem on a scholarship, and went on to receive three master’s degrees, in education, Jewish Studies, and Hebrew literature from Israeli institutions.

Two deadly suicide bombings in Buenos Aires – of the Israeli Embassy in 1992 and the AMIA (Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina) Jewish Community Centre in 1994 – shaped Bergman’s life and strengthened his Jewish identity. He was supposed to have a meeting at AMIA on the Monday morning that it was attacked, but cancelled it as his third child, Talia, had just been born. “I then had to be at the morgue for people to identify the bodies. I will never forget this in my life.”

Young people in his community wanted to do something meaningful in the face of this horror. They pushed him to lead a weekly protest outside parliament, shaming the government with a timeline of how many weeks it was since these two bombings with no arrests. “I did this every Monday for two-and-a-half years,” said Bergman. “We started with 20 people and then it became mass public demonstrations. We blew a shofar in the public square. This made me into a social activist.”

Bergman was mentored by the future Pope Francis, forming a strong friendship with him after attending a meeting to confront Argentina’s political, economic, and social crisis in 2001. “He taught me to respect differences and serve society. That’s real power. He’s a master of communication through symbols.” Bergman still maintains correspondence with the pontiff, who likes to hand-write his letters but now dictates them to his secretary.

Bergman was the first rabbi elected as a congressman in the country, which he cites as evidence of the integration of the Jewish community into Argentine society. He then went on to serve as minister of the environment and sustainable development in President Mauricio Macri’s cabinet from 2015 to 2019. “We lost the next election, which wasn’t really my fault,” he joked mischievously.

“Being minister of environment was my most rabbinical work, the peak of my rabbinical career. I could put tikkun olam into action. I felt like Noah building his ark and being laughed at by his neighbours. The flood has now come.” He’s most proud that six national parks were proclaimed during his tenure.

Bergman now steers the WUPJ, “with 1 200 congregations in 50 countries and seven regions”.

“We seek to serve the Jewish people and humankind. We pioneered the empowerment of women, long before #MeToo. It’s 50 years since female rabbis were ordained in the United States. Now there are also many women in leadership positions in Jewish communities, even in Orthodox communities.”

We need to distinguish Jewish spirituality from politics, which is about power, Bergman said. “Orthodox Judaism doesn’t always respect and accept diversity,” he said, “I prefer not to use energy on internal divisions. I want to welcome those Jews who feel they don’t belong, they should come back home. I’m against assimilation, but I support integration. To ‘reform’ is an action, it’s an ongoing process.”

He said he was inspired by the stories of Jews in the struggle after visiting the Apartheid Museum. “I have learned a lot from this visit, from local leadership and the very welcoming community. We as Jews need to clearly define what value we can add to the world. Today, we need to be resilient, flexible, and open-minded, especially post-COVID-19. It’s a catalyst for change. It’s very Jewish, from every bad thing to make a good one. I feel at home here – South Africa is similar to South America.”

His key message is that Jewish South Africans have much to contribute to the wider society, and they should be proud of all aspects of their identity.