Featured Item

How to touch ‘every thread in the weave’ of SA’s Giant Flag

As South Africa is plunged into darkness thanks to Eskom’s extensive loadshedding, one project in the middle of the desert may light the way.

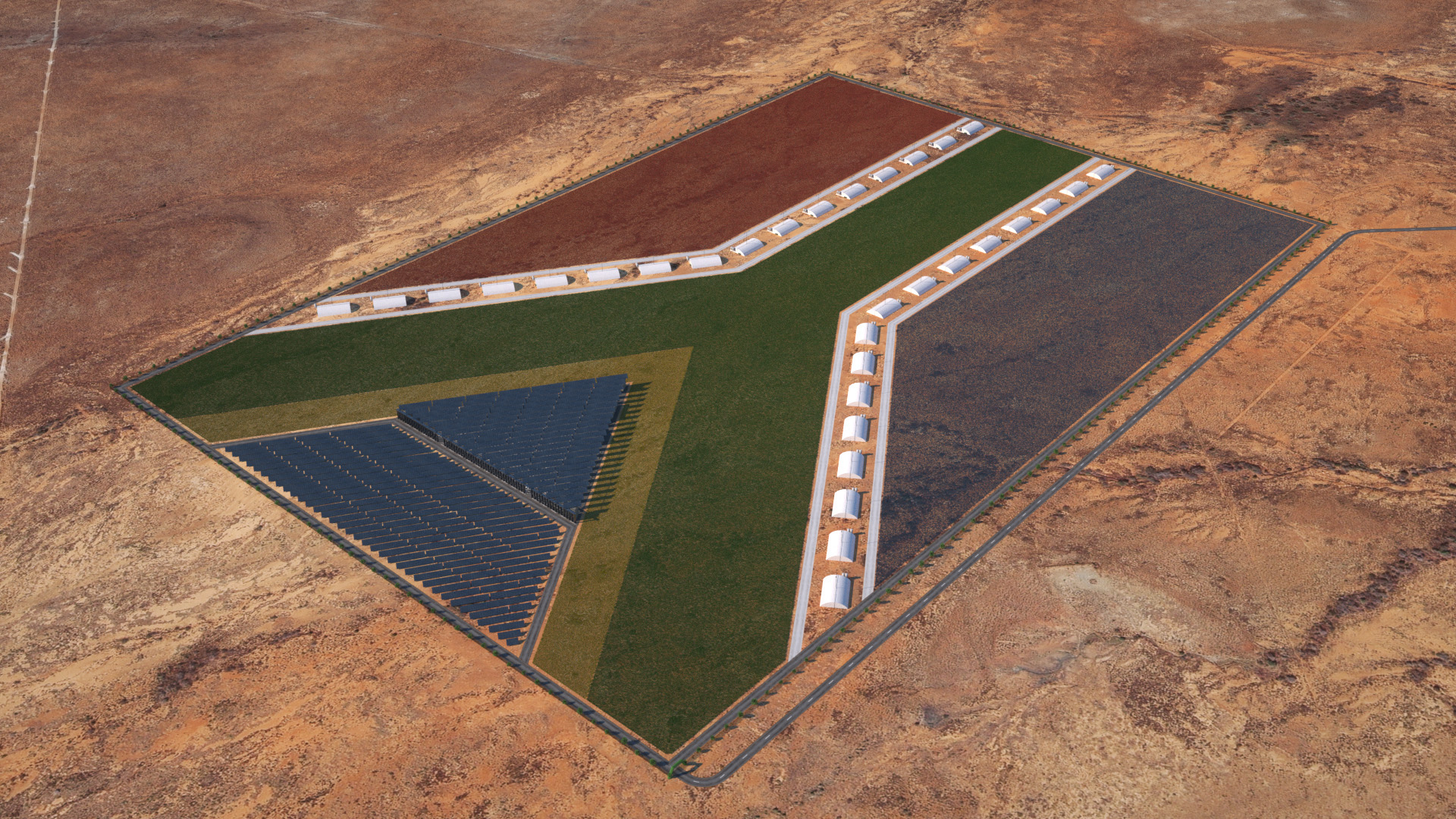

Guy Lieberman’s Giant Flag has been named by CNN as “one of 10 ideas to change the world”. He and his team have been working towards building a flag — viewable from space – made up of tens of thousands of desert plants, greenhouses, a tourism precinct and a 20-megawatt solar field in the Camdeboo region of the Karoo on the outskirts of Graaff-Reinet.

Through the creation and maintenance of the Giant Flag, the project envisions creating hundreds of “green-collar” jobs, with women constituting a majority of the labour force. The solar panels in the black, blue and red part of the flag are the heart of the project, and will have the ability to provide power to the equivalent of 20 000 homes.

Lieberman made aliya from Johannesburg, some years ago but remains closely connected to South Africa, especially through this project. “South Africa has the ideal landscape and climate for renewable energy projects like the Giant Flag,” he says. “These could provide a local source of power to smaller towns and even cities. Not to oversimplify things, but it takes a blend of political will, technical repair and economic impetus to get us to that point. The country has all the natural resources required as well as all the need in the world to motivate for this to happen.”

When he started the project in 2014, “the vision didn’t even include solar power”, recalls Lieberman. “At that initial stage it was only plants in the colours of the flag. But within the first year, it dawned on me that converting the black triangle to solar power would give the project the necessary economic grounding it needs.

“However, the Independent Power Producers [IPP] industry and national regulation at the time weren’t ready for small projects like ours to enter the grid easily. Now the regulation is there, but technical problems in being able to access the grid is the primary hold up.”

At this point, the solar panels aren’t generating electricity because the project has been delayed by various obstructions. “Most of these have been external, and most of them we’ve overcome. Initially, it was the high barrier to entry for IPPs to enter the market. That eventually opened up. The issue we’re facing now is the fact that the Eskom grid cannot receive power from IPPs due to technical problems on the line.”

They are planning to generate 20MW of electricity, “a substantial increase on our initial figure”, Lieberman says. “Once the generation allowance for IPPs leapt from 1MW to 100MW, it suddenly made the Giant Flag a viable project in the eyes of solar developers,” says Lieberman. “Because we had already secured so many of the necessary authorisations and approvals and were essentially considered “shovel ready”, we were approached by several renewable energy operators to collaborate with them.

“We ultimately partnered with a solar developer who proposed a generous and socially sensitive economic model. The Giant Flag Trust is a nonprofit organisation, with a deep focus on addressing the socioeconomic realities of the communities in and surrounding Graaff-Reinet. The income from solar would provide an economic baseline upon which to build out the rest of the project — the greenhouses, tourism precinct and plantations.”

Asked what the electricity will be used for, Lieberman says, “There are two strategies here. One, to provide power to the Dr Beyers Naudé local municipality. Or, wheeling it through the national grid to qualified ‘offtakers’ — large energy users anywhere in South Africa who want to use renewable energy to power their facilities without the bother or expense of adding their own solar installations on their buildings. These could be banks, supermarkets, office blocks, hotels, malls, factories, universities or similar institutions.

“The local municipality would have been ideal, but like many smaller municipalities across South Africa, the economic realities, including pre-existing and substantial indebtedness to Eskom, complicated things. This is unfortunate because if it was possible to proceed with the municipality, we would have had a great story of a local solar field empowering a small Karoo town.”

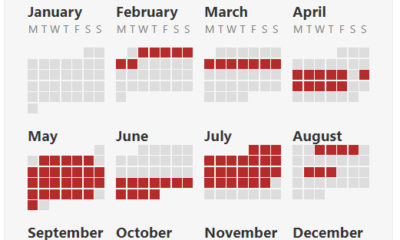

Lieberman says that as a whole, the Giant Flag project has experienced a mix of progress and setbacks over the past year. “The pause in operations and the holding pattern while we wait for approval to access the grid is tough to maintain. So much rests on the success of the solar project. I last visited in March this year, but I’m in daily contact with my colleagues on the ground there.

“One of the most beautiful aspects of the project has been the local people that I get to work with,” he says. “Our board meetings are literally the vision of a unified South Africa. We have the former ANC mayor of the municipality; the current municipal chief financial officer; the Democratic Alliance shadow minister for public works; and, until he died tragically from COVID-19, Moyikwa Sisulu [Walter Sisulu’s grandson]. Our staff includes a black woman Economic Freedom Fighters activist and an Afrikaans administrator. And then there’s me, the only Jew at the table. We’re all very close! Almost every time we gather, the meetings end in eruptions of laughter.”

When asked how the Jewish community can support the project, Lieberman says, “We’ve established that our current obstacle is grid access. What might be helpful is to prepare for when this obstacle is removed and the gates to the grid are open. At that stage, perhaps the opportunity would be for those who deal with the kind of hardware we would need to consider how they might assist, in-kind. Solar panel providers, manufacturers of transformers, high-grade fencing, building materials, security and communications technology – these are the kinds of things the project will ultimately need. If we can lower the hard costs of the build, we can ultimately increase the benefits for the local community.”

At such dark times in South Africa – literally – he says, “My sense is that now is the time to double down and ‘give hard’. Do whatever you can to shift the small details consistently, to attend to the problems that are in front of you and that you can address. We’re particularly good at that. It trickles upward. Invest your energy in the rare beauty of the place, engage it, and appreciate it. This cannot be overstated. Travel locally, spend money there. Rediscover why you’re in South Africa. Enjoy the South Africans around you. This can happen regardless of how Eskom is behaving.”

To the South African Jewish community, he says, “For well over 100 years, the Jewish community has participated in the creation of the South African fabric. We’ve touched every thread in the weave. There’s significance in acknowledging this because the reality is that this hasn’t changed. It will be this way for as long as a Jewish community exists in South Africa.”