Lifestyle

The inside out world of photographer Roger Ballen

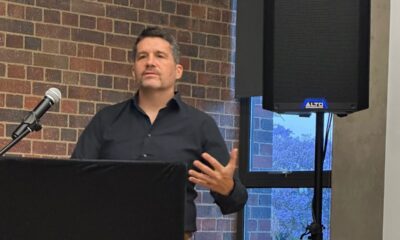

Internationally acclaimed Jewish photographer Roger Ballen recently spoke at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre about his 40 years in the industry. The SA Jewish Report caught up with him.

You’re originally a geologist from the United States. What brought you to South Africa 40 years ago?

In 1982, I found myself in South Africa working in mineral exploration, travelling across vast expanses of the countryside. But though my profession provided me with a living, there were questions about my existence that it didn’t begin to answer. I needed to use the camera to excavate layers of my inner life.

In common with my work, peering below the earth’s surface for hidden treasure, I began to do the same with the people and places I photographed, trying to pierce their outer layer to reveal their elemental selves. During these travels in the South African countryside, perhaps because I was an outsider or because I felt compatible with isolated places, I was drawn to the unique aesthetic of the dorps or small towns.

What drew you to photography?

I bought my first camera, a Mamiya, when I was 13. My mother was then, in the early 1960s, working for Magnum (a top international photo agency) for some years. Through her, I was exposed to the work of many photographers, some of them now considered historically important. In this milieu, there was a complete belief in the value of photography, particularly its ability to convey meaning in a socio-documentary context. The Magnum photographers were my idols, my heroes. My mother hung their photographs all over the walls of our suburban house in Rye, New York. I ended up assimilating their images, and by the time I went out to take photographs seriously, at around 18, I had a clear idea of the level I was aiming at.

Which award means the most to you and why?

The Photographer of the Year Award at the Arles Festival in France in 2001. This was my first big award, and it gave me the confidence to dedicate more of my time to photography.

Describe how your art has changed over the years.

From 2003 onwards, I felt that there was no need to place real people in the theatre I was creating. I wanted to eliminate any and all items that could be seen to relate to culture, society, economics, and identifiable locales, and to create purely psychological images. At the same time, portraiture disappeared from my photography, as it was clear to me that I couldn’t make the transition to another aesthetic as long as viewers were focusing on the state of the human subjects in the image to the exclusion of all other aspects.

What does the term “Ballenesque” mean?

Beginning around 2002, the human face started to disappear in my imagery, replaced by broken body parts, drawings, animals, and objects. As a result, the images started to express a more complex reality that became more difficult to define and which could be best described as Ballenesque. I became increasingly involved in video, installations, collage, and painting. My goal was – and still is – to produce parallel art forms that expand and enhance one another to generate a wider, more encompassing aesthetic.

For this reason, I tend to regard my photographs as a kind of psychological projection rather than a truthful documentation of reality. My express intention, particularly as my work has evolved, has been not to create pictorial realms that mirror the world as we see it, but to create images that externalise scenes of the mind itself.

In press photography, it’s that decisive moment that photographers look for. Is this integrated into your work?

I believe the so-called “decisive moment” is the most important aesthetic concept that separates photography from other art forms. Hardly an image of mine over five decades doesn’t take this concept into account.

What do you look for in a subject?

My subjects vary from people to animals, drawings to objects. Everything in my photograph is a subject working towards a greater meaning.

You often use animals where humans would be, and vice versa. What are you saying here?

An animal is truth, a reflection of purity. I’m intrigued by animal psychology. If you want to try to understand the deeper parts of human behaviour, sometimes a good place to start is with the animal. Each species of animal brings with it its own mythology, and when you bring that mythology into a photograph, it offers unlimited possibilities for creating deeper meaning relevant to the human condition.

You use a lot of mystery and the unexplained in your work. How do you do this, and why?

It’s my hope that my images will assist people to better integrate their various states of mind. In other words, I hope that my photographs can break through layers of mental repression and allow different sides of people people’s minds to communicate with each other. It’s my belief that unless a substantial proportion of humanity is able to unshackle mental repression, the condition of the species won’t improve substantially.

On the other hand, my photographs need to be enigmatic. When you ponder the nature of life and death, you begin to understand what enigma is. If I produce pictures that have an enigma, then perhaps they make a profound statement.

Describe your background and the importance of Judaism and the Jewish community in your life?

I was born in New York City to Jewish parents whose family originated from Russia. My grandparents never lost their Jewish identity, and passed it on to their children. Our family adopted the reform Jewish faith, and I and my sisters had Bnotmitzvah. My two children, Paul and Amanda, as well as my wife are very conscious of their Jewish identity. Paul and Amanda were educated at King David Victory Park. We’re all proud of our Jewish heritage.

Why hold this event at the Holocaust & Genocide Centre?

The goal of my images is to help viewers make peace with their inner self, and to work through layers of repression. Ultimately, the Holocaust was the result of individual failure to come to terms with deficiencies.

You built an arts centre up the road from the Holocaust Centre. Tell us about it.

About 10m up Jan Smuts Avenue from the Holocaust Centre, I built The Inside Out Centre for the Arts, which will open in 2023. It will host exhibitions and educational events that will focus on psychological relevance to Africa and the South African community and have some relationship to my aesthetic.