World

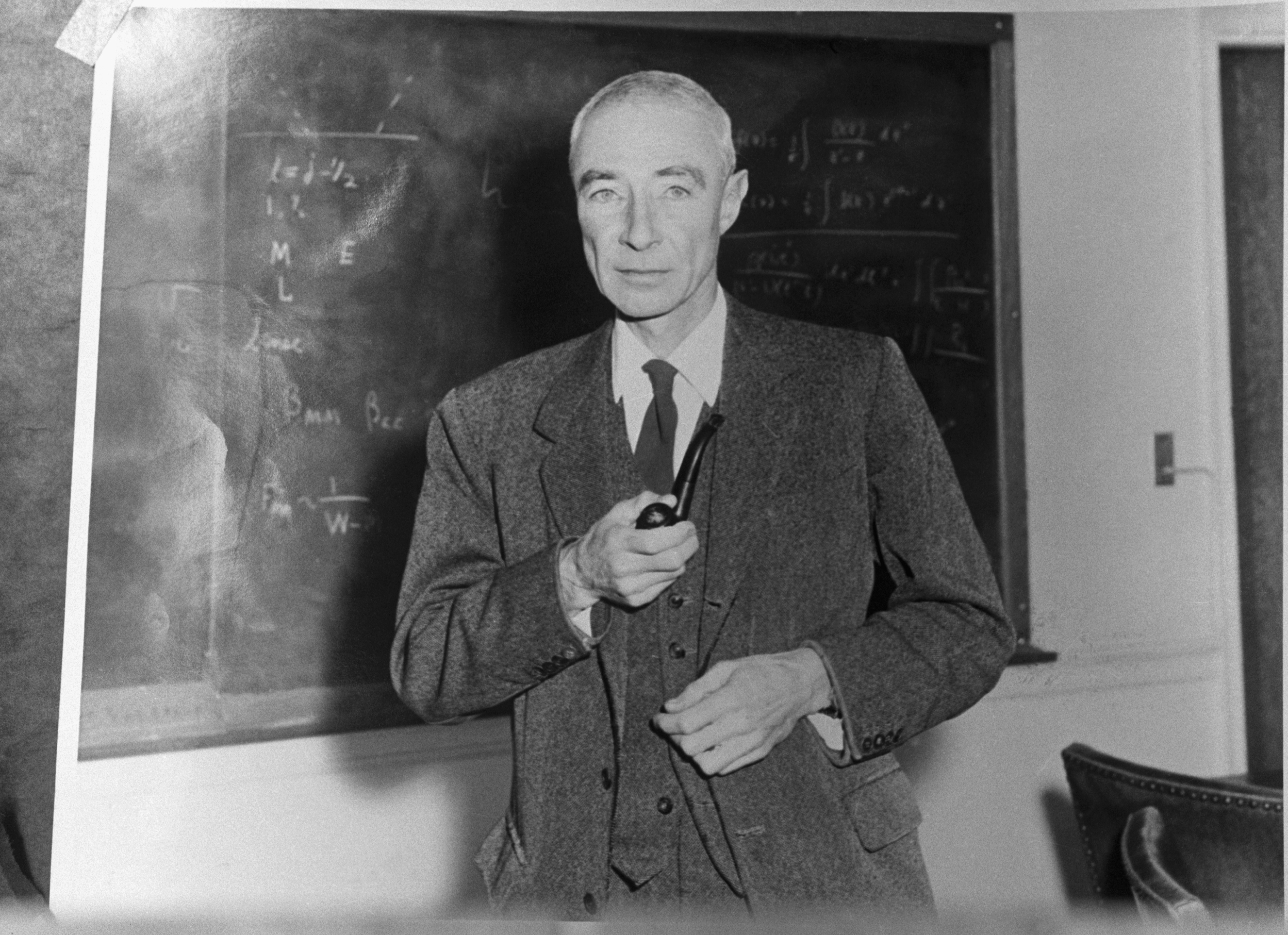

The Jewish story behind Oppenheimer

JTA- Friday wasn’t just “Barbie” release day – moviegoers also filled theatres across the United States to see Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer biopic.

Many hope it will answer a question that has long divided Americans and the country’s understanding of its history: who exactly was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb?

Oppenheimer’s name has become “a metaphor for mass death beneath a mushroom cloud”, in the words of Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, whose 2005 book, American Prometheus, was adapted into Nolan’s film. But to fully understand the physicist, biographers have looked for clues in his belief system – an ethical code grounded in science and rationality, a fiery sense of justice, and a lifelong ambivalence toward his own Jewish heritage.

Oppenheimer was born in 1904 to German Jewish parents rapidly rising into Manhattan’s upper class. His father, Julius Oppenheimer, came from the German town of Hanau and arrived in New York as a teenager – without money or a word of English – to help relatives run a small textile import business. He worked his way up to full partner, won a reputation as a cultured fabrics trader, and fell in love with Ella Friedman, a painter whose German-Jewish family had settled in Baltimore in the 1840s.

Their secular household embraced American society. The Oppenheimers never went to a synagogue or had a Barmitzvah for their son. Instead, they aligned themselves with the Ethical Culture Society, an offshoot of Reform Judaism that rejected religious creed in favour of secular humanism and rationalism.

Although his parents were first and second-generation German immigrants, Oppenheimer always insisted that he didn’t speak German, according to Ray Monk, the author of Robert Oppenheimer: A Life Inside the Center. He also maintained that the “J” in “J. Robert Oppenheimer” stood for nothing at all, even though his birth certificate read “Julius Robert Oppenheimer”.

“To the outside world, he was always known as a German Jew, and he always insisted that he was neither German nor Jewish,” Monk told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “But it affected his relationship with the world that that is how he was perceived.”

Oppenheimer’s academic brilliance became a flimsy shield against the antisemitism that orbited his life. He entered Harvard just as the university moved toward a quota system over concerns about the number of Jews being admitted.

After earning a bachelor’s degree from Harvard in 1925, he conducted research at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and completed his PhD at Göttingen University – in pre-Nazi Germany – under Max Born, a pioneer of quantum mechanics. Before he got to Cambridge, though, a Harvard professor wrote him a recommendation that captured the institutionalised prejudice in academia: “Oppenheimer is a Jew, but entirely without the usual qualifications.”

Oppenheimer returned from Europe to teach physics at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California at Berkeley. While at Berkeley, he tried to secure a position for his colleague, Robert Serber, and was rebuffed by his department head, Raymond Birge, who said, “One Jew in the department is enough.” He didn’t push back on the decision, later hiring Serber to work on the Manhattan Project.

Until the 1930s, Oppenheimer was resolutely indifferent to politics. Though he studied Sanskrit along with science and read classics, novels, and poetry, he took no interest in current affairs. But a profound shift occurred in Oppenheimer during the mid-1930s as he watched family, friends, and great scientific minds crushed under the tides of Nazism in Germany and the economic collapse at home.

“I had a continuing, smouldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany,” he said in his testimony before the 1954 United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) hearing, which would end with him losing his security clearance over past associations with communists and support for left-wing causes “I had relatives there, and was later to help in extricating them and bringing them to this country. I saw what the Depression was doing to my students, and through them, l began to understand how deeply political and economic events could affect men’s lives.”

In addition to rescuing family members, while teaching at Berkeley, he earmarked 3% of his salary to help Jewish scientists escape Nazi Germany. By World War II, his drive to defeat Germany would propel him to direct the Manhattan Project – the top-secret development of an American atomic bomb – at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

He was an unlikely candidate for the post. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had already marked him as politically suspect for communist sympathies. He was a theoretical scientist, not an applied scientist with experience in leading a laboratory. He wasn’t yet 40 years old. But Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Groves chose Oppenheimer as the Manhattan Project’s director in 1942 partly because he showed a burning sense of imperative.

“Oppenheimer said to Groves, ‘Look, the Nazis will have their own bomb project and it will be led by Heisenberg, who’s one of the leading nuclear physicists in the world. We need to move, and we need to move quickly,’” said Monk.

Other prominent Jewish scientists felt compelled to join. Six of the project’s eight leaders were Jewish, along with a significant number of Jewish technicians, scientists, and soldiers up and down the ranks, some of them refugees from Europe.

Although two atomic bombs ultimately dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not Germany – Germany had already surrendered by then – Oppenheimer was hailed as a hero for his role in ending World War II.

But only nine years later, he was humiliated before the AEC and stripped of his security clearance. Lewis Strauss, the chairperson of the AEC, became suspicious of Oppenheimer for opposing the development of a hydrogen bomb. Oppenheimer pressed for international control of nuclear weapons, believing the purpose of the atomic weapon was to end all war.

Strauss also developed a personal hatred for Oppenheimer, who could be arrogant and supercilious. They came from very different Jewish backgrounds: Strauss was a committed Reform Jew with modest origins who worked as a traveling shoe salesman instead of going to college. He identified closely with his faith, and served as the president of New York’s Temple Emanu-El from 1938 to 1948.

In the film, Strauss is portrayed as having secretly orchestrated Oppenheimer’s downfall at the hands of the AEC in part by collaborating with Hungarian-Jewish physicist Edward Teller, who agreed with Strauss on the necessity of the hydrogen bomb.

Bird writes an account of Oppenheimer running into Albert Einstein, one of the most famous Jewish figures of the 20th century, shortly before the 1954 hearing. The two were friends and colleagues at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study.

According to Bird, Einstein urged his friend not to go before the AEC. He said Oppenheimer had already done his duty for America, and if the country repaid him with a witch hunt, he “should turn his back on her”.

Oppenheimer’s secretary, Verna Hobson, who witnessed the conversation, said he couldn’t be dissuaded. “He loved America,” she said, “and this love was as deep as his love of science.”

Einstein responded by calling Oppenheimer a “narr” or “fool” in Yiddish.