Lifestyle

Godwin writes about exile and goodbyes

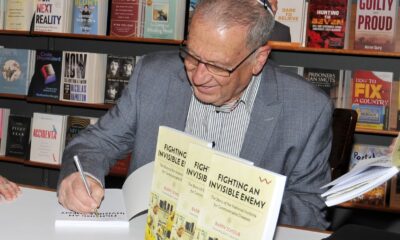

Zimbabwe-born author and journalist Peter Godwin has just brought out his latest book called Exit Wounds: A Story of Love, Loss and Occasional Wars. The SA Jewish Report caught up with him soon after his latest memoir was launched.

In your second book, When the Crocodile Eats the Sun, you wrote about your father’s revelation about being a Holocaust survivor and how his family were killed in Treblinka. What impact did that have on you?

Well it didn’t change my lived life up to that point – I was already middle-aged by then – but it changed my perspective on my lived life. And it helped to explain my father, his depression, why he was somewhat distant, and why he never really talked about his family or his background.

At 15 he had been sent to England for the summer holidays to learn English and was supposed to return to high school in Warsaw in early September. But it was 1939. When Hitler invaded Poland on 1 September, my father couldn’t get back, and his family couldn’t get out, and he never saw them again. He eventually joined the Free Polish Army and had a very active war. He stayed on in England and met my mother when they were both students in London. At that point he was still openly Jewish, and she was from a rather posh Church of England family who disapproved of their relationship. After they married, he Anglicised his name, and they emigrated to Africa. He hid his Jewish identity from us, his children, until right at the end of his life, when he, in effect, reintroduced himself to us.

As a journalist, did you do research into what happened to your father’s family? If so, what did you find out? Do you perhaps have any remaining Jewish family who survived the Holocaust? If so, what do you know about them, and have you tried to connect with them?

One of the first things my father asked me to do when he revealed his Jewish background to me, was to do a Red Cross search on his family members who had been killed in Treblinka. But, like for most people killed in Treblinka, there were no records of their deaths. However, we do have a few relatives, in Poland, in France, and in America. I contacted them, and I visited them.

I was eastern European correspondent for The Times in London in the 1980s, covering the rise of Solidarity in Poland – and had no idea at the time that I had any Polish heritage. My father drew up family trees from memory, and told me about his history, but it was obviously hard for him as he had kept it all a secret for 50 years. He knew I would write about it, and I had his permission to do so. And I did, in When a Crocodile Eats the Sun.

What have you told your own children about their Jewish heritage?

They are a quarter Jewish, and they understand that. It is incorporated into their identity, though they grew up in the complex cross-cultural mosaic of New York City.

As for most of us, your parents left scars. How did that impact on you becoming a parent yourself, if at all?

I found that it left me wanting to be a hands-on parent, to have a close relationship with my boys as they grew up, and by and large, I did. Often, you are tempted to try to become the parent you wish you’d had. But a friend of mine, a paediatric psychiatrist, warned me: parent the child you’ve got, not the child you were. Which is good advice, I think.

It took you a long time to return to writing another book. Why?

Stuff happened. My mother died, my marriage collapsed, the COVID-19 pandemic. Life intervened, you could say!

What drew you to writing about “emigres, exiles, and refugees”?

Well, I feel like an exile myself. I have lived in many places, on three continents, Africa, Europe, and America – a double-dipping soutpiel – and the experience made me interested in the themes of identity, family, and home. What it means to “belong”. Almost anywhere I go, people ask me, “Where are you from?”

You give so much of yourself in your books, giving people information about you – with such vulnerability – that one rarely normally finds out about another person. Why did you choose to do that, and has it affected your life?

I think that – counterintuitively – the universal resides in the detail. My challenge in the past, in writing about southern Africa, was to write for two different readerships: southern Africans, who are familiar with what I describe, and those from somewhere like America, many of whom would find it difficult to find Zimbabwe on a map. How to write in a way that doesn’t bore one or bewilder the other? My goal is to write well enough about the detail that afficionados get the thrill of recognition, while painting a detailed enough word picture for strangers to be able to imagine it. While this new book is set mostly in America and the United Kingdom, the spirit and essence of southern Africa infuses every page.

How do you feel about Zimbabwe now?

Just sad, really. Flat. I spent much of my adult life, first as a human rights lawyer, then as a journalist, trying to support democracy activists in Zimbabwe. And we are no nearer to it being a democracy. I don’t think I helped to move the needle at all. That Zimbabwe’s considerable potential has been wasted is tragic.

What drew you to writing Exit Wounds now? What do you hope readers will take from it?

This is my most interior book. It’s a kind of accounting, a reflection. It is, I hope, both funny and sad. But ultimately uplifting, I think. In the end I’m struck by how privileged we are to be alive, by the ecstasy of existence. The book is many things: an extended farewell to my mother, an examination of memory, a celebration of diversity, a love letter to New York. It is full of motifs drawn from natural history: bird migration, plant propagation. And poetry too. My mother in old age was suddenly able to declaim the poems of her childhood.

What inspired the title, Exit Wounds?

It was a training course on hostile environments and battlefield first aid that I was sent on when I worked for the BBC. One of the classes was taught by a Royal Marines combat doctor who described in excruciating detail, with accompanying slides, the way that a bullet kills you. That once it hits you, it tumbles, so that it’s not usually the entry wound that kills you, it’s the exit wound. The book bears an epigraph by Dickens: ‘Life is made of ever so many partings welded together.’

What are you doing now, other than writing books?

I teach at university, and occasionally I still commit to journalism. But writing books is mostly what I concentrate on now.

What can we expect from you next?

I think I’m done with memoirs! I’m planning to write a novel next.

- Exit Wounds: A Story of Love, Loss and Occasional Wars is available at all leading physical and online bookstores.