Holocaust

Innocence lost: Bak’s art depicts childhood in Holocaust

“Our world is composed of broken things, with bruises, cracks, and missing parts, but we must learn to live with it.” These are the words of Lithuanian Jewish artist Samuel Bak, whose work depicts the horrors of the Holocaust he witnessed in his childhood in Lithuania and at a displaced persons camp.

“His work must also be remembered in the context of the hatred that we can see in the world today, particularly after the attacks Hamas carried out against the people of Israel on 7 October 2023,” said Lithuanian ambassador to South Africa, Rasa Janaukaitė, at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre at an event showcasing the artist’s life on 14 October.

“His thought-provoking pages reflect the deep form of his experience during the Holocaust. He challenges us to remember the past while urging us to keep hope,” Janaukaitė said.

Bak, who has family living in Cape Town and visited the country a few years ago, was born in Vilna in 1933, just as Adolf Hitler came to power. In Lithuania in 1941, there were 41 000 Jews. By the end of the war in 1945, only 2 000 remained in four small labour camps.

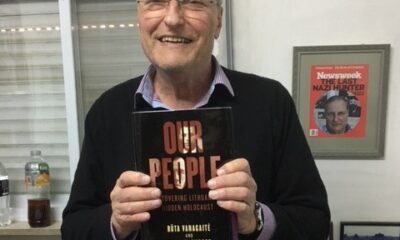

A book detailing his life in the context of his art, Art and Life: The Story of Samuel Bak, was launched at the event. The author, South African art historian Dr Ute Ben Yosef, described Bak as “the greatest contemporary artist of our time”.

Said Ben Yosef, “The Bak family were secular Jews, intellectuals, inventors, artists, realists, and dreamers. Each of them worshipped little Samech, their child prodigy, who twisted them all around his little finger. They sheltered him from the storm clouds that began engulfing the Jewish wilderness, and they all helped nurture his artistic gift.”

Bak was eight years old when his childhood ended. His family was forcibly removed from their home, and sent to the Vilna Ghetto. It was then that his artistic talent was first recognised. A painting of his was displayed in an exhibition in the ghetto when he was nine.

In a painting titled Interruptions, Bak depicts the loss of innocence and childhood with a teddy bear, a soccer ball, and a little hoop.

All of his grandparents were murdered in Ponary Forest outside Vilna.

Bak’s father was taken to a labour camp, where Bak and his mother joined him after being kicked out of a Benedictine convent where they had stayed for eight months.

Said Ben Yosef, “The living conditions in the camp were terrible. Sam witnessed terrible things like the gruesome hanging of a family of three – mother, father, and son – who tried to run away. They were hanged in a sadistic way.

“But life in this camp went on. Children played. They started playing Nazis and Jews, perpetrators and victims. Then, on 27 March 1944, trucks entered the camp. Whistles blew. The inmates were ordered to bring their children to an assembly for vaccination. His mother was about to join the crowd when a friend pulled them into a corridor and they hid him in a storeroom filled with burlap sacks. And then the sound of machine guns exploded. It dispersed with pistol shots. It was a Kinderaktion.”

Ben Yosef said Bak depicts this time in his life through images of teddy bears, showing the loss of innocence and childhood that many like him experienced. “The trauma of these days, filled with the naked fear of death, never left him,” Ben Yosef said.

In many paintings, he depicts bandaged teddy bears representing the murdered children, chess pieces representing the tenuous insecurity of the Jewish pawns whose lives depended on chance, flightless birds and angels, and broken china representing destroyed lives. Bak’s trees are cut away from the ground, unwilling to be rooted in the blood-soaked Ponary Forest. There are crematoria chimneys, broken tablets of the law, with bullet holes through the sixth commandment – “Thou shalt not kill.” There are representations of the yellow star Bak was forced to wear, crumbling shtetl ruins, distorted Magen Davids, Shabbat candles, and shtetl houses on boats of stone unable to sail in the sea of indifference.

Similarly, in many of his paintings, Bak depicts the famous image of a young boy with his hands held up in surrender taken out of the Warsaw Ghetto. “This became Bak’s prototype for all children that lived through the Holocaust,” Ben Yosef said.

Bak and his mother escaped the camp by being smuggled out in potato sacks on his father’s back. They were able to find refuge in the same Benedictine convent.

Three days before Vilna was liberated in 1944, Bak’s father was shot dead.

After liberation, Bak and his mother stayed in a displaced persons camp in Munich. It was in this camp that for the first time, Bak was able to get an art education and further his artistic skills.

Said Ben Yosef, “He received a scholarship to study at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts under professors who had been famous artists. In 1956, he went to Paris to study art at the École des Mosaics. He needed to acquire the visual language of modern art.

“In Paris, he absorbed the zeitgeist of first-world Europe,” Ben Yosef said. “In his art, he was able to release a hidden power, combining the style of old-world Europe and the modern day. In the years since, he has continued to draw inspiration from his childhood and Jewish upbringing.”