Holocaust

Grandfather’s Nazi past raises more questions than answers

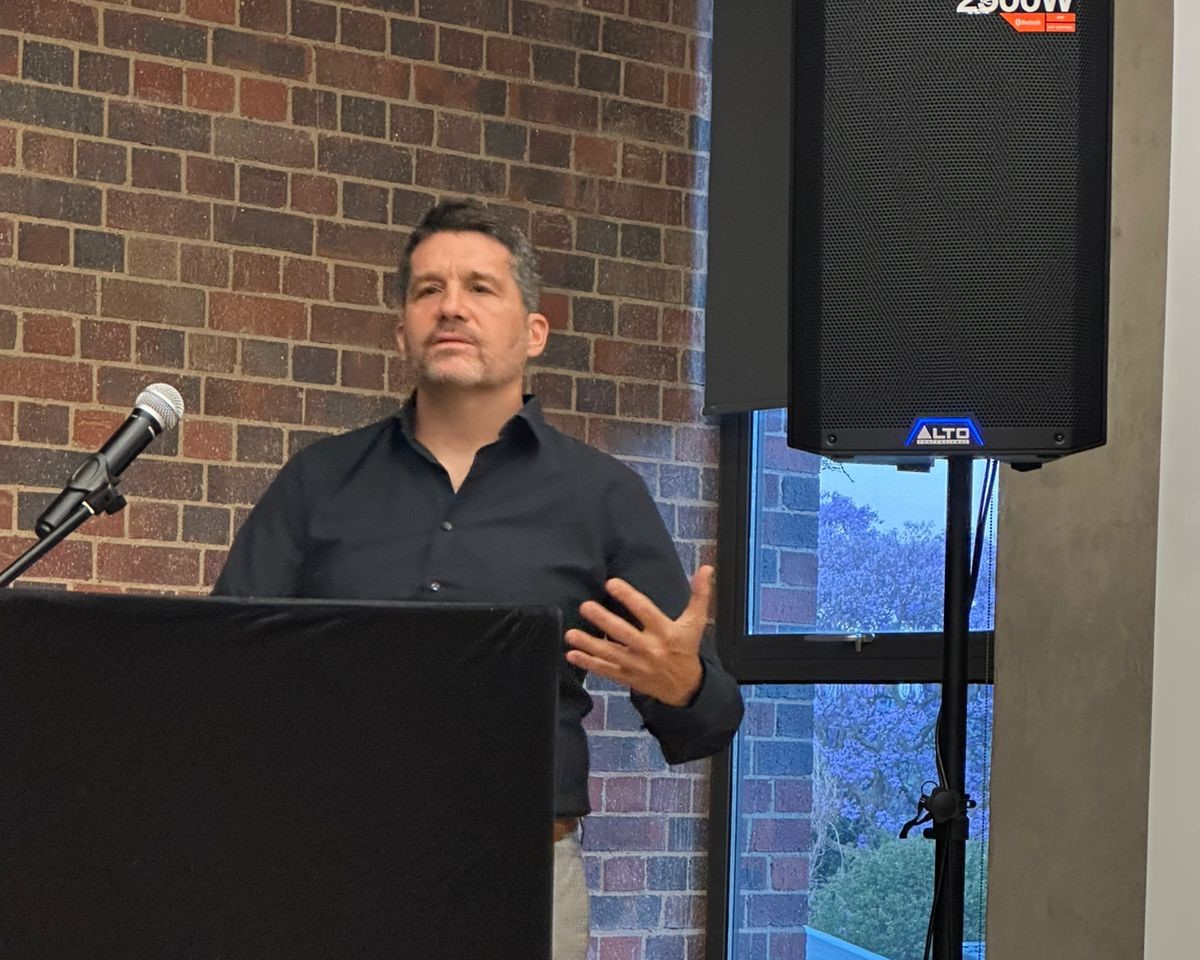

It’s never easy for young Germans to confront their family’s World War II past, but German author Lorenz Völker decided 20 years after his grandfather had passed away that he needed to know if he was a Nazi.

Völker, speaking at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre on 6 November, said that when he was growing up in the 1970s and asked questions about the war, the responses he got were inadequate. “That was when children [in Germany] were questioning their parents for the first time, and those answers were unsatisfactory,” he said.

Völker embarked on a six-year journey of researching his grandfather’s past, knowing that with no information to start with, it would be an arduous task. He battled for answers to what his grandparents did during the war, particularly in the light of the fact that three out of four grandparents were members of the Nazi Party and the war years hadn’t been discussed.

After all his research, he knew that the man he loved and saw as a warm and caring grandfather had been a card-carrying Nazi, but he couldn’t determine whether he actually believed in Hitler’s ideology or used it as a means to improve his career.

Völker’s maternal grandfather, Johannes Adolf Wilhelm Dombois, was a state prosecutor from 1935 to 1947 in Potsdam, Germany. “Like many other law officials working with the National Socialist state, he was a member of the National Socialists, but he was someone who could disengage from the system of justice,” said Völker.

He said his grandfather voluntarily joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP or Nazis) in 1937. That same year, he was given a permanent prosecutorial position.

Völker said he felt angry to find out that his grandfather was an NSDAP member. However, his personnel records, his denazification papers, and a report detailing his experiences didn’t make his beliefs about Nazi ideology any clearer.

“He was trying to build a career,” said Völker. “He started in 1933, finding himself in that different political situation.”

In photographs, Völker saw his grandfather wearing his Nazi membership badge as well as being the loving grandfather that he remembered him to be.

In his personnel records held by the State of Hesse, a German province, there is a quote from the chief public prosecutor saying, “Dombois [his grandfather] has fully grasped the essence of the new era,” and he found out that his grandfather had participated in a one-week training course on new anti-Jewish laws for prosecutors.

Among his papers, Völker found court documents of one of the 33 cases his grandfather prosecuted in which he took on a prominent Nazi, Max Schettler. In 1935, a 17-year-old Jewish girl named Susanne Busse and her boyfriend were looking for some private space in a park when Schettler caught them being intimate, and threatened them. Schettler then attempted to rape Busse, and was subsequently sentenced by Völker’s grandfather to one and a half years in prison.

The Schutzstaffel (SS) attacked the court and the judgement, saying, “One can hardly imagine that six national socialists can be outwitted by a 17-year-old Jewish girl.” However, Völker explained that the state supported this judgement. Busse was allowed to emigrate to the United States after this ordeal.

In the reasoning for this judgement, Völker said his grandfather was said to have been “defending the law against the party”, which meant a lot to him.

The case gave Völker hope that his grandfather was a good man, a fact he felt was reiterated by his denazification documents that claimed he was a bystander or follower, not a perpetrator.

His role wasn’t so innocent in another of his cases, however. Völker said his grandfather played a significant role in the judgement and sentencing of a young Jewish man, Alfred Lehmann.

Lehmann was the same age as Völker’s grandfather, and they were on a similar path in that they were trained in the same court in Potsdam. Though Völker’s grandfather was able to become a prosecutor for the state, Lehmann wasn’t able to practice at all because he was Jewish.

In 1938, Lehmann was caught in “violation of the racial laws in a particularly serious case”, meaning that he had a love affair with a non-Jewish woman.

Lehmann was sentenced to two and a half years in prison by Völker’s grandfather for this. After his imprisonment, he was sent directly to Sachsenhausen concentration camp without further trial and from there to Gross-Rosen concentration camp, where he died on 9 September 1941, at the age of just 32.

After all his work, Völker found it difficult to picture the man that he saw as a warm, cosy lovable man at 63, to be what he was raised to believe a Nazi was – a cruel person wearing the brown shirt and going about the destruction of others.

He said when he tried to bring it up with his mother, she was reluctant to dig too deep as she didn’t want to believe that he was a Nazi.

“Yes he was a Nazi, he was a member of the NSDAP, and had the badge,” said Völker, “but did he have the ideology? I still don’t know.”