OpEds

Reflections of an Afrikaner at Auschwitz

One of the great Afrikaner philosophers of the previous century, NP van Wyk Louw, remarked that the love and respect we develop for a nation isn’t primarily based on its achievements, but on its hardships.

This is the type of observation that seems strange at first, but it becomes more obvious the more you think about it. I would add only that it’s the combination of hardship and accomplishment that serves as a source of appreciation.

My great-grandfather was only a toddler when he was taken captive with his mother during the (second) Anglo Boer War and taken to a concentration camp. Through his mother’s resolve, they were able to escape en route to the camp, after which they had to survive in the veld for several weeks. Had they not escaped, I cannot say with certainty that I would have been here today. That was the first war in which concentration camps were used on a large scale. Tens of thousands of Boer women and children died in those camps. The same goes for black Africans.

Once the atrocities of that war became known, the Afrikaner people fostered the hope that such atrocities would never repeat themselves. Within decades, that hope was dashed.

During a recent trip to central Europe, I made sure to fulfil my longstanding wish to visit Auschwitz. It’s difficult to express the emotions that gripped me upon walking through the camp and seeing what remains of this place where unspeakable horror occurred on a scale that’s unimaginable.

In scale, the atrocities of the Anglo Boer Wars are by no means comparable to those of the Holocaust. However, being a descendant of the survivors of our own historical atrocities, and having an emotional connection with my own history, made the hardship suffered by the Jews so much more relatable on an emotional level.

What’s even more remarkable is the extent to which the Jewish people were able to rise from the ashes to become an immensely successful people again. Herein, too, lies a certain comparison with the Afrikaner people, considering the rapid industrialisation of South Africa after the Anglo Boer War.

This happened largely as a result of the Helpmekaar movement – a mutual aid movement which, literally translated, means helping each other – when in the aftermath of the war of 1899 to 1902 and the Afrikaner Rebellion of 1914, the Afrikaners declared that “’n volk red homself” (a nation saves itself).

I published a video on YouTube with some impromptu thoughts and observations on my Auschwitz experience. Most of the responses were supportive, however there were also a few negative responses, some even highly derogatory and antisemitic.

What concerns me most is the growing sense of frustration pertaining to the mere topic of the Holocaust.

Douglas Murray recently remarked that our generation would probably be remembered for its inability to make sense of World War II. It’s obvious that we should learn some extremely important lessons from that war, but what exactly those lessons are seem not be to be quite as obvious.

And so, many on the ideological left would like us to believe that we can learn from the Nazis that the very notion of cultural, national, or communal identity provides the foundation for evil. If this is true, it would imply that communal matters such as heritage and tradition, cultural diversity, and a particular perspective on history and religion are inherently bad and have to be destroyed in order to achieve “progress”. Not only that but, according to this perspective, those who cherish these things should be regarded as part of the problem.

Unfortunately, we seem to be seeing more of this as time progresses and “wokeness” has taken over the political discourse in the Western world. To accuse people of racism for expressing opinions that one disagrees with has become commonplace. So common, in fact, that the accusation has lost its value. Even though racism is an abhorrent thing, a growing number of people have lost all concern about being labelled racist – and I might add, for good reason. Bizarrely, some even regard such accusations as a token of honour.

Instead of rethinking this approach, wokeness has doubled down. All of a sudden, people who say things they disagree with aren’t racists anymore, but Nazis. This was especially evident during the recent American election, with some in the mainstream describing Trump as Hitler and his supporters as Nazis.

This has had a double negative impact. First, likening people who say offensive things with Hitler and the Nazis is a form of Holocaust denialism, as it not only suggests that such people are the same as the Nazis, but that the Nazis were in fact the same as these people. Regardless of what you may think of someone like Donald Trump, equating him to Hitler necessarily implies equating Hitler to Trump. I have had my own flabbergasting experience of this sort of rhetoric when a news anchor of a mainstream TV network in South Africa confronted me during a live interview, saying that to be a black person living in a township in South Africa today is just as bad – or perhaps worse – than being a Jew in a Nazi concentration camp. This is a glaring expression of Holocaust denialism.

Second, continued superficial accusations of Nazism necessarily lead to a situation where the accusation loses its value. Accusing people of Nazism is the ideological equivalent of quantitative easing – of printing more money to grow the economy. And so, as with accusations of racism, the accusation loses its value. Imagine for a moment how much damage ought to be done for people to start wearing accusations of Nazism like a badge of honour. Yet, somehow, the idea doesn’t sound that far-fetched anymore.

The way I see it, there is only one way forward. It implies fostering mutual recognition and respect, not just between individuals, but also between nations and communities, appreciating that having different opinions about contemporary politics is often the result of differing historical experiences. The way forward isn’t to reduce humankind to the lowest common denominator, which necessarily implies the destruction of culture and tradition, but to recognise diversity as it ought to be recognised.

This brings me back to NP van Wyk Louw, who added, with reference to Evelyn Beatrice Hall, that the fundamental principle of liberalism is that we may differ from what others say, but should fight to the death for their right to say it, and the same principle should be applied to nations. Nations and communities may have different views on current affairs, but attempting to force them from the outside to change on the inside isn’t just futile, but dangerous.

As to what the most important lessons of World War II are, I’m sad to say that this conversation is far from over.

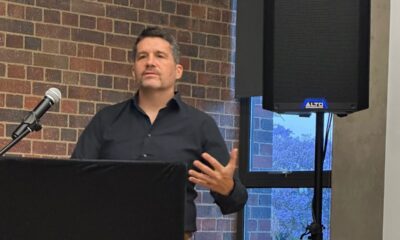

- Dr Ernst Roets is a South African attorney, author, and documentary film maker. He’s the executive director of The Afrikaner Foundation, and head of policy at the Solidarity Movement. The foundation was established as part of the Solidarity Movement with the goal of encouraging international co-operation and support.