OpEds

Praying for our dear son

It has been a harrowing week for my family and me. Our beloved son, Noam, sustained serious injuries while serving in Lebanon, courageously defending our people and our land. As I write these words, he remains intubated and sedated, but stable. We, along with countless others, continue to pray for his complete recovery.

We are suffering deeply for our son – the anguish of his pain, the weight of his medical struggle, and the daunting path that lies ahead. This week has been soaked in tears, a cascade of sorrow and heartache that seems unrelenting. Yet, amidst this sea of sadness, we optimistically cling to hope and faith that the same strength that carried him will guide us through this turbulent storm. I’m deeply grateful to everyone who has held our son in their hearts and prayers.

This painful week has been a stark reminder of the intricate emotional challenges life places before us, testing our resilience and faith. Life often challenges us to carry a mixture of conflicting emotions, holding joy and sorrow side by side in a delicate and painful tension.

The midrash portrays Avraham’s emotional state during the Akeida (binding of Isaac) as a profound paradox. He sheds tears of sorrow at the prospect of sacrificing his son, yet his heart brims with joy at the opportunity to fulfil divine will and shape the destiny of Jewish history. Avraham was called upon to embody two opposing emotions simultaneously. Perhaps for this reason, Hashem designed the heart as a multi-chambered organ, capable of holding feelings that seem to contradict one another.

Similarly, the Gemara in Bava Batra teaches that upon the passing of a close relative, one recites the beracha of dayan ha’emet, humbly accepting the divine decree. Yet, upon receiving the inheritance from the deceased, the very same individual is instructed to recite the beracha of hatov ve’hameitiv, expressing gratitude to Hashem. This delicate juxtaposition reflects the profound challenge faced by Avraham at har haMoriah: the ability to hold contrasting emotions in tension, balancing grief and gratitude, while maintaining unwavering faith in moments of profound complexity.

I have wrestled deeply with the delicate balance between joy and sorrow. Despite the severity of his injury, my heart overflows with gratitude that Noam’s life was spared and that he has a positive prognosis. He endured the impact of a direct drone attack, yet Hashem, in His infinite kindness, shielded my precious son. I thank Hashem for this miraculous gift of life, and continue to pray that He will watch over my dear Noam, granting him strength and guiding him toward a complete and lasting recovery.

Yet, my heart remains heavy. My son’s condition is still precarious, and b’ezrat Hashem, when he recovers, the path forward will be long and arduous. I’m overwhelmed with grief for the suffering he must endure.

Beyond the struggle of toggling between sadness and grief, this week I found myself grappling with the complexity of each emotion, as each carried charged secondary responses. My gratitude that my son’s life was spared felt tinged with guilt when I thought of the soldier who was killed in the same attack, and certainly when I considered the immense pain and suffering that so many have endured over the past year. Am I allowed to feel even this small trace of joy and gratitude? It also felt wrong to feel even minimal gratification while my son still suffers and while we continue to live in a state of constant and uncertain stress.

Yet, not feeling gratitude toward Hashem felt like a denial of the protection He granted my son. How can I not thank Hashem deeply for protecting my beautiful Noam from this deadly attack?

It’s one thing to reconcile two opposing emotions; it’s much harder when each emotion is layered with secondary feelings of guilt and concern about being insensitive or imbalanced. I hope that I will find a way to remain grateful for the miracle while not overlooking our suffering nor the immense suffering of others.

This trauma opened my heart in a new and visceral way to the immense suffering our people have endured. As much as we try to empathise with others’ pain, as much as we shed tears for their suffering, it’s difficult to understand the depth of their anguish until we ourselves experience something that begins to approximate it.

It was important to us to learn about every step of my son’s journey to the hospital. It brought me great reassurance to hear from the soldiers who saved his life how quickly they responded, and how they acted with such precision to keep him alive. Similarly, speaking to the doctors and hospital staff who admitted him, knowing that my child was under the care of people who were doing everything they could to alleviate his suffering, was a source of comfort. Though I cannot speak to him, I take solace in knowing he has been cared for every step of the way.

But my mind cannot escape the unimaginable suffering of the families of the hostages. To not know anything about your child’s fate, and to live with the knowledge that they are in the hands of brutal terrorists who have no respect for human life and are consumed by hate, must be an unbearable burden, one that requires immense strength just to wake up each day. I apologise to them if I haven’t felt this grief as deeply as I should have. I will try harder.

Likewise, it brought me immense comfort to hear that my son’s unit operated exactly as it should have. Having been attacked by a drone, they feared a terrorist infiltration, and my son immediately ran from his tent to guard the perimeter. After being attacked by mortars and taking shelter, he rushed to a lookout post, following protocol, at which point the second drone fell directly on the guard post. His friends quickly rushed to provide medical care for him and for the other wounded. Within little more than an hour, he was in the operating room. This rapid response undoubtedly saved his life.

I have been haunted all week, thinking about situations where soldiers are injured or killed in accidents, friendly fire, or, chas v’shalom, other malfunctions. It’s agonisingly painful to suffer a loss without a storyline to hold onto, without the clarity of a defined sequence that can offer some sense of peace or understanding.

The war persists, and our sacred struggle to safeguard our land and protect our people remains unwavering. While the headlines have shifted to politics, diplomacy, and elections, it’s crucial to remember, especially for those far away where the echoes of war may seem distant, that pain and hardship endure.

Please keep our pain and suffering front and centre as you continue your daily routine. Please continue praying for my dear son, Noam Avraham ben Atara Shlomit.

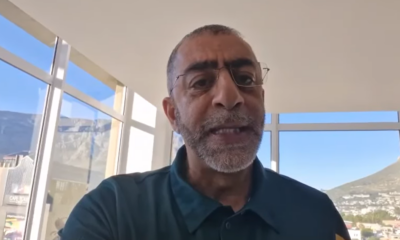

- Moshe Taragin is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has smicha and a Bachelor of Arts in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a Master’s degree in English literature from the City University of New York.