Banner

Wiesel gave Holocaust a face, world a conscience

SARAH WILDMAN

WASHINGTON

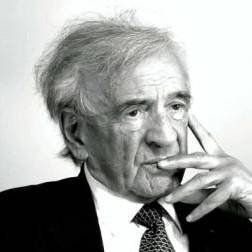

Pictured: President Barack Obama lunches with Elie Wiesel in the Oval Office’s private dining room in this file photo, on May 4, 2010.

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA

A philosopher, professor and author of such seminal works of Holocaust literature as “Night” and “Dawn”, Wiesel, perhaps more than any other figure, came to embody the legacy of the Holocaust and the worldwide community of survivors.

“I have tried to keep memory alive,” Wiesel said at the Nobel peace prize ceremony in 1986. “I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.”

Often, he would say the “opposite of love is not hate, it is indifference”.

The quest to challenge indifference was a driving force in Wiesel’s writing, advocacy and public presence. Though he considered himself primarily a writer, by the end of the 1970s he had settled into the role of moral compass, a touchstone for presidents and a voice that challenged easy complacency about history.

Wiesel spent the majority of his public life speaking of the atrocities he had witnessed and asking the public to consider other acts of cruelty around the world, though he drew the line at direct comparisons with the Holocaust.

“I am always advocating the utmost care and prudence when one uses that word,” he told JTA in 1980.

President Barack Obama, who met frequently with Wiesel and took his counsel, said he had been a “living memorial”.

“Along with his beloved wife Marion and the foundation that bears his name, he raised his voice, not just against anti-Semitism, but against hatred, bigotry and intolerance in all its forms,” Obama said in a statement. “He implored each of us, as nations and as human beings, to do the same, to see ourselves in each other and to make real that pledge of ‘never again’.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Wiesel was “bitterly mourned” by the state of Israel and the Jewish people. “Elie, the wordsmith, expressed through his extraordinary personality and fascinating books the triumph of the human spirit over cruelty and evil,” he said in a statement.

Wiesel won a myriad awards for his work, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal and the National Jewish Book Award. “Night” is now standard reading in high schools across America. In 2006, it was chosen as a book club selection by Oprah Winfrey and, nearly half a century after it was first published, spent more than a year atop the best-seller list.

“There is no way to talk about the last half century of Holocaust consciousness without giving Wiesel a front and centre role,” said Michael Berenbaum, a professor at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles and former director of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s research institute. “What he did, extraordinarily, was to use the Nobel Prize as a tool to call attention to things, and as a vehicle to scream louder, shout more, agitate more.”

Born in the town of Sighet, Transylvania, then and now a part of Romania, in 1928, Wiesel was deported to Auschwitz in 1944 with his family. He was 15. His mother and one of his sisters would disappear forever when the family was forced aboard the cattle cars, murdered immediately. His father, who travelled with him to the camps, died of dysentery and starvation in Buchenwald before liberation. Two sisters would survive the war.

In “Night,” Wiesel describes pinching his face to see if he is dreaming when he sees the murders of infants.

“In those places, in one night one becomes old,” Wiesel told NPR in 2014. “What one saw in one night, generations of men and women had not seen in their own entire lives.”

Wiesel was liberated from Buchenwald in 1945. He went on to study at the Sorbonne and moved to New York at the end of the 1950s, where he lived in relative obscurity. He worked hard to find a publisher for “Night”, which initially sold poorly.

“The truth is in the 1950s and in the early 1960s there was little interest and willingness to listen to survivors,” said Wiesel’s long-time friend Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, who had read a copy of “Night” in Israel in the early 1960s. “In 1963, someone told me this author is alive and well in New York City and I somehow managed to find him and go see him.”

Wiesel was “gaunt” and “working as a freelance reporter, a stringer, for a French newspaper, an Israeli newspaper and a Yiddish newspaper – and for none of the above was he making a living,” Greenberg said.

In the late 1960s Wiesel finally began to emerge as one of the pre-eminent voices in Holocaust literature. By the end of his career, he had written some 50 books.

In 1972, he enthralled Yeshiva University students with his excoriation of the American and American Jewish leadership for its silence during the Holocaust.

How many Jewish leaders “tore their clothes in mourning?”, Wiesel said. “How many marched on Washington? How many weddings took place without music?”

His 1966 book reporting the plight of Soviet Jews, “The Jews of Silence,” made possible the movement that sought their freedom.

In 1978, Wiesel became the chairman of the Presidential Committee on the Holocaust, which would ultimately recommend the building of a Holocaust museum in Washington. As his public presence grew, he began to visit the sites of other genocides.

In 1985, Wiesel’s reputation grew beyond the Jewish world when he challenged President Ronald Reagan on live television over his intention to visit a German cemetery that housed the remains of Nazi soldiers. In the Oval Office to receive the Congressional Medal of Achievement, Wiesel chastised Reagan.

“This is not your place Mr President,” Wiesel famously said. The president visited the cemetery anyway but changed his itinerary to include a visit to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Wiesel challenged the White House again in 1993, when he charged the newly-inaugurated President Bill Clinton to do more to address the atrocities then unfolding in Yugoslavia.

At the inauguration in 1993 of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Wiesel said, clearly: “I don’t believe there are answers. There are no answers. And this museum is not an answer; it is a question mark.” That question mark, he applied to global atrocities, as well as historical ones.

His later years saw him wade into politics. He was friends with Obama but also loudly chastised the president for calling for an end to settlement construction and for brokering the Iran nuclear rollback-for-sanctions-relief deal, positions that led to criticism, even from long-time admirers. His very public support for Netanyahu was also questioned.

The final years of his life also saw financial turmoil. His personal finances and $15,2 million in assets of the Elie Weisel Foundation for Humanity were invested with Bernie Madoff, who was convicted in 2009 of fraud. Wiesel’s fortune and the reserves of his organisation were wiped out.

And yet he did not cease his work. Just months after the scandal broke, in June 2009, he led Obama and German Chancellor Angela Merkel on a trip to Auschwitz.

“Wiesel never pretended that he understood the Holocaust. He spoke of it as a horror beyond explanation, a black hole in history. As the virtual embodiment of the catch phrase ‘never forget’, he did more than anyone else to raise awareness of the Holocaust in American life,” said Ruth Franklin, author of “A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction.”

Wiesel is survived by his wife, Marion, and a son, Shlomo. (JTA)

nat cheiman

July 6, 2016 at 1:40 pm

‘A man among men . A beacon for humanity. B. D. E’

Avner Eliyahu Romm

July 6, 2016 at 7:10 pm

‘I wou;d like to beg to differ: Wiesel was one of those who incited the world, or the West, against Serbia and against the Serbian people, without ever getting confused by facts. And the facts are that Serbia and the Serbian people defended themselves from mercyless enemies (Boer farmers have mercyless enemies too). And how comes it is \”wrong\” to compare the suffer of non-Jews, let’s say Serbs, at the hands of the Nazis and Ustase during WW2, to that of the Jews, while it is \”right to accuse them of doing \”what Nazis did to the Jews\”??? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G8gzDVm2Rxw‘

nat cheiman

July 7, 2016 at 11:03 am

‘I don’t get it.’