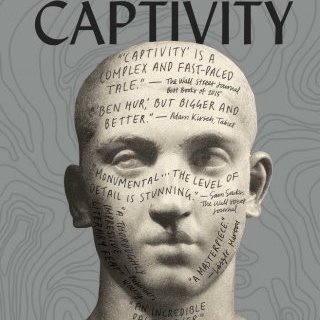

SA

A Captive read, flaws and all

STEVEN KRAWITZ

It tells the story of Uri, a Jewish-Roman citizen who is 17 years old when the novel begins. Uri, whose Roman name is Gauis Lucius, is informed by his father, Joseph, a respected but marginal member of the TransTiberium Jewish community, that he is to accompany the official Jewish delegation to Jerusalem.

The delegation is taking the community’s half-shekel per person’s donation to the Temple and is scheduled to arrive in time for Pesach. What starts out as Uri’s late antiquities road trip, soon develops into both a gripping narrative of imperial political intrigue and a documentary/travelogue around the Mediterranean Basin’s Jewish communities.

Spiro has researched the time period so thoroughly that he is able to describe the minutiae of an almost infinite list of relevant topics. At times the level of research drowns the narrative and Captivity lapses into textbook mode. Some might feel this to be a weakness of the book but, in many ways, it makes the experience of reading Captivity more rewarding.

The period covered by Spiro was one of great change and importance for the Jewish people and Spiro offers an accessible one-volume opportunity for the brave reader to fully immerse themselves in this world.

Politically, Rome was the hegemonic ruler over the Mediterranean and exerted thorough control over all parts of Israel, forcing the Jewish elites to enter into compromises and accommodations with the Romans.

Rome had broken up King Herod’s Jewish empire after his death, appointing prefects and puppet kings over the provinces carved out of the Jewish state. Geographically the diaspora communities of especially Alexandria and to a lesser degree Rome, were important centres of Jewish life, influence and wealth and would become even more so after the second Temple was destroyed, an event covered towards the end of the novel.

Spiritually the learning and practice of Torah and mitzvot in both Israel and the Diaspora, is documented well by Spiro.

Upon arrival in Israel, Uri experiences the tensions between Greeks and Jews in Caesaria, the port on Israel’s coast built by Herod as a miniature version of Alexandria. This creates the tone for the heavy-handed Roman treatment of rebellious Jewish elements in Jerusalem on Pesach, the repercussions of which will result in the beginning of Christianity, covered in the last part of the book.

The tensions also presage the wider tensions between Jews and Greeks that will result in the Bane of Alexandria, a protracted, horrific anti-Semitic attack on the 300 000 strong Jewish community in Egypt, an event Uri is witness to.

In Jerusalem Uri is hit unconscious by the delegation’s leader and wakes up in a jail above the Kohein Gadol’s residence. He is in prison with two thieves and a messianic Jewish preacher. These three prisoners are crucified during Pesach, their identities are obvious.

This leads Captivity to have a Forrest Gump feel and this continues throughout the book. Uri is released from jail and taken to dine with Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor and Antipas Herod, the late emperor’s son and a pretender to the title king of the Jews.

Uri is taken to the Judean countryside and kept in hiding for a few months. The intrigue continues when he is travels to Mount Gerizim, the shrine of the Samaritans and witnesses a massacre carried out by a neighbouring army, but blamed on Pilate.

For a book heavy on research, the absence of the history of the Samaritans is glaring. The strained relationship between the Jews and the Samaritans is expertly conveyed.

Uri travels to Alexandria and stays with Philo, a famous Jewish philosopher and brother to the Alabarch, who holds the monopoly rights to collect all import duties in Alexandria.

Captivity is good on nudging the reader to compare the world it recreates to the Jewish and wider worlds of 2017. In awe of Alexandria, Uri studies in its famed Gymnasium and is present in the city when the month-long pogrom is unleashed on a community who felt more Alexandrian than the Greeks of the city.

Disillusioned, Uri is able to escape a city whose politics are so poisonous they will ultimately destroy it. He returns to Rome after an absence of a few years. His life in Rome, the politics of the Roman empire, the destruction of the Temple, the start of the Nazarene sect and the changing fortunes of Jews throughout the empire, now become the focus of the narrative.

Once again Uri has a front row seat to history, personally knowing Tiberius, Nero and Claudius, depraved, psychotic caesars with strong anti-Semitic attitudes. Uri becomes a conduit to power for the Jewish community.

If there is a flaw in Captivity, it is neither the length of the book nor the amount of research overpowering the story. Rather it is a number of inexcusable mistakes and misrepresentations of Torah laws and concepts.

People were purified after touching a dead human body with the ashes of the Red Heifer, not the red doe. Yibum, levirite marriage, occurs when a man dies without children, leaving his widow to either marry her late husband’s brother or do Chalitzah, thereby severing all links to her late husband’s family.

In Captivity a long convoluted case is presented where the brother-in-law presents evidence that his sister-in-law was divorced, but he insists on doing Yibum as he does not want his nephews to inherit from his dead brother.

There are a number of other halachic inaccuracies which blight an otherwise magnificent read.

For all its flaws, Captivity is still a remarkable work of fiction and an important read for anyone interested in this turbulent and fascinating time.