Lifestyle/Community

A lament for South Africa

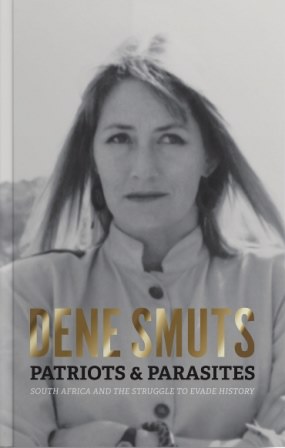

Jeremy Gordin reviews the book, ‘Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History’, by the late Dene Smuts.

JEREMY GORDIN

Jeremy Gordin published his review of:Patriots and Parasites: South Africa and the Struggle to Evade History by Dene Smuts (Quivertree Publications, Cape Town, 344 pages, R295), this week on Politicsweb. It is reprinted here with permission.

1.

I want to start this review of the late Dene Smuts’ Patriots and Parasites, published in November, with a personal note. This is not good journalism and also irritating to some readers. But I’d like to try to show just what a remarkable eye-opener, or rather brain-opener and even heart-opener, reading this book turned out to be.

I haven’t of late, like Hamlet, “lost all my mirth”. But I have lost interest in local politics, politicians, political debate, and related issues. In truth, I find them pretty damn tedious. Why? Well, Smuts provides part of the answer. In 1998, delivering the parliamentary Vote of Thanks to Bill Clinton, Smuts said: “Here at the Cape of Good Hope … the tide of history has turned towards hope … hope into history!” However, she then continues (in 2016, at the end of her book), “Now, our tide has ebbed – economically, socially and politically.”

In short, I guess I have lost interest because I agree with Smuts; like her and many others, I am disappointed about where South Africa is in 2016/17 CE. And so, for one thing, I no longer barrel out of the house to buy the latest political book or to be the first to get hold of the day’s or week’s newspapers.

But I have for many years worked with Smuts’ sister, Helene, on her educational and “art” publications – and she brought me Dene’s book a few days ago, mentioning that for a variety of reasons the book had not received the coverage it deserved.

Smuts’ daughter, Julia Smuts Louw, who did much of the final edit of the book (I understand), and has written one of the excellent Festschriften at the end of the book (the others, all good, are by Tony Leon, Antjie Krog, and Jeremy Gauntlett SC), said she just wished people knew – in the run-up to Christmas – that the book is in the stores.

2.

So I said, yeah, I’d write a review now. But, for the reasons given above, I wasn’t initially as excited as I might have been had I been offered, say, an all-expenses-paid trip to Granada.

The book is Smuts’ account of the so-called transition era, as seen through the lens of her 25-year career as an opposition MP (1989-2014) – though she also writes, I’m pleased to say, about her prior career as editor of Fair Lady.

Smuts focuses on the putting together of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights (“Negotiating the new South Africa”). Then she moves on to what is called “The Unravelling of the non-racial accord” and the entrenchment of cronyism under President Jacob Zuma, and her fight to help protect the freedom of the media and the independence of the judiciary (specifically the JSC, the Judicial Service Commission, and the NPA, National Prosecuting Authority).

As I started reading the book, two points quickly became clear. One was that Smuts did her research. Notwithstanding being a journalist and a politician (both notably philistine-ish pursuits), she was, it seems, reading far and wide all her life – and knows exactly what she is writing about.

Discussing how PW Botha, via Naspers’ management, ramped up the pressure on her, as editor of Fair Lady, over the 1986 publication of a story on Winnie Mandela – and how Naspers management said it was the magazine’s unsatisfactory performance, not the Mandela story, that made them unhappy – she gives us chapter and verse, i.e. the full circulation numbers. Does this seem an obvious thing to do? Yes, of course; but, if you paid attention to the recent parliamentary hearings on the SABC, you might have noticed that, sadly, the journalists who “testified” might have been impressive on a certain level, but their knowledge of hard facts and figures was almost nil.

Another example: Sometimes, you might suspect Smuts is a trifle starry-eyed, such as when she starts explaining that the Constitutie van den Oranje Vrijstaat of 1854 actually contained remarkably enlightened provisions and that therefore “FW de Klerk was less on the Last Trek – the title of his autobiography – [than] on a trek back to first principles.” But beware of calling Smuts starry-eyed, or calling her anything for that matter, because she then gives cogent chapter and verse, supporting her contention.

Second, Patriots and Parasites is one of the most elegantly-written local books that you will come across: clean, lean, and to-the-point. In fact, it’s so lean and to-the-point that, about 85 pages in, I started thinking, “Geez, Louise (or Dene), let your hair down a little – let’s hear some personal stuff, such as about your family and where you come from, spiritually and physically.” Well, right on cue, there it was (p.90) – the story of the Smuts family and death at the hands of the British during the Boer War.

And where did Dene Smuts come from? Or, putting the question differently, what galvanised Smuts, made her what she was?

The answer (or mine, anyway) is quite scary; or I, at any rate, find it so. Smuts was “a believer”. She really believed – certainly for most of her life – that colonialism and apartheid, discrimination and injustice, could be overcome and that, with proper constitutional safeguards, South Africans could live harmoniously and productively together.

3.

So, given that Smuts started and spent most of her life as “a believer,” this book is, I realised as I reached the end, a kind of threnody (“a poem, speech, or song of lamentation, especially for the dead”) for South Africa.

But here’s the thing. This threnody – if that’s what it is (for I’m not sure Smuts and others would agree with me) – is, via the re-telling of Smuts’ own experience, a meticulous and incisive analysis of where it all went wrong during the past 22 years.

Smuts is far too intelligent to say that “It’s all because of Zuma” (or Zuma having many wives, or the Guptas, or the firing of Nhlanhla Nene, or whatever). She touches on nearly all the aspects of the unravelling of the dream, though particularly those in the fields in which she was active – the Constitution, the judiciary, race relations and freedom of the media. And suddenly, in 344 pages, we begin to see a clearer picture of what happened.

Try this for example (p. 169): “True moments of catharsis came with Sharpeville in 1960 and Soweto in 1976, both inspired by African nationalist and Black Consciousness political formations. [Former President Thabo] Mbeki seems, to me, to have tried to trigger a new Africanist catharsis in order to unravel the 1994 accord and create a new African order. By 2016, sections of the student movement were courting anarchy toward the same goal, openly expressed in anti-colonial and anti-white sentiment. Faceless, leaderless, lacking strategy except when they found a concrete focus in the question of university fees, lacking also Mbeki’s subtlety and sophistication, they were – nevertheless – Mbeki’s spiritual children.”

There have been, and will be, other books explaining where things went wrong in the beloved country. But this a spell-binding book, a must-read, especially for students of politics and South Africa, and is enthralling even for those who think they’ve lost interest in politics.

4.

I mentioned that at the end of the book, Smuts wrote: “Now, our tide has ebbed – economically, socially and politically.” What I did not mention is that she continues: “This does not mean that [the tide] will not come washing in again. It will: all we have to defeat this time, however hopeless it may sometimes look, is misrule and the erosion of everything we have achieved. It will be easier, this time.”

Let’s hope Smuts – a believer till the end, despite everything she has set down in this book– was right.

- Note: There has been some suggestion, in the Politicsweb comments section, that it was “strange” that the cause of Smuts’ “unexpected death” on April 21, 2016 was “not made public”. Smuts’ daughter, Julia Smuts Louw, says that the cause of death was a heart attack.