News

A new way of looking at Holocaust resistance

TALI FEINBERG

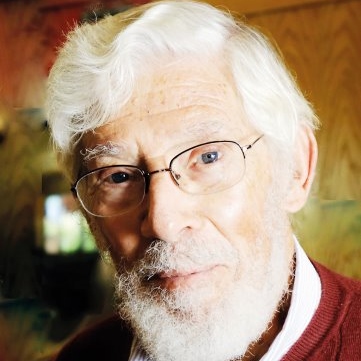

“Stealth altruism is a new concept I have developed to highlight non-militant acts of sustained, secret care given by victims to other victims, both strangers and kin alike, knowingly undertaken at risk of limb and life,” he said following talks at the Cape Town and Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centres.

“Another new concept of mine is the ‘help story’, of which stealth altruism is a prime component. I contrast it with the ‘horror story’ which tells what perpetrators did to victims. The ‘help story’ tells what victims did for one another.”

Examples of acts of stealth altruism include the high-risk sharing of scarce clothing and food among starving camp prisoners, the taking on by stronger prisoners of some of the workload of weaker prisoners, and the “adoption” by women prisoners of the suddenly orphaned children whose parents had been sent to the gas chambers.

The professor began researching this issue after 43 years as an applied sociologist. Having recently retired, he asked himself what his next project would be. “In short order, I discovered a costly deficiency in the conventional Holocaust narrative, one I have since devoted my life to correcting.”

He noticed that in most Holocaust education and museums there was nothing that adequately captured what he read as stealth altruism in survivor memoirs. “So, as I had done in 33 earlier books of mine, I developed new concepts. Once I started my research, I became engrossed with bringing overdue attention to the matter.”

Professor Shostak says that stealth altruism and “the help story” applied both to Jews and non-Jews during the Holocaust. “They apply to all human beings, and have over history significantly aided the survival and ascendency of our species. In my book, I devote an all-too-brief chapter to non-Jews who dared to provide stealth altruistic help to captive Jews.”

One survivor Shostak interviewed said that she thought most survivors had moments or turning points when someone helped them in this way. If not, they wouldn’t have survived. According to the professor, “in more than 200 survivor memoirs I’ve read, the writer tells of giving or getting secret high-risk altruistic care. According to the field of positive psychology, we are hard-wired to help one another, even in concentration and slave-labour camps operated by deniers of this humanistic truth.”

So why has this aspect of resistance been left out of many Holocaust narratives? “Since the war’s end in 1945, the focus in Holocaust memorialisation has been on the horrific criminality of the Third Reich and its collaborators in 24 captive countries. Holocaust centres have been ‘horror-focused’ as they thought this the best way to assure ‘never again,’” he says.

“All such horrific events, however, contain both the perpetrators’ behaviour, and the victim’s fierce struggle to retain their humanity and improve their chances of survival. Captivity in a Nazi concentration or slave labour camp included both a ‘horror story’ and a ‘help story’ – even if 43 of 48 Holocaust centres studied by me for my 2017 book do not honour this.”

The professor notes, however, that the South African Holocaust & Genocide centres do have this narrative. “The centres admirably salute Jewish [and gentile] upstanders who risked all to help others survive. The centres are compact, and yet thorough; selective, and yet authoritative; unsparing, and yet not ghoulish; artful, and yet also realistic.

“Staff at the centres show a deep understanding of and keen appreciation of the ‘help story’. They cover the components of compassion, militant resistance, and collaboration under death threats, and model how to achieve a still finer Holocaust narrative,” he says. “The Cape Town Centre, in particular, pioneers a creative approach in how it uses volunteer docents that merits close attention in all such institutions.”

For parents and educators who want to incorporate stealth altruism into teaching about the Holocaust, he suggests looking at his website or his 2017 book on the topic [the royalties of which go to the Children’s Holocaust Museum in Israel]. This has about 100 specific examples to draw on.

“An unlimited number are still to be extracted and employed from over 10 000 memoirs in English. Likewise, almost every day’s news media has accounts of stealth altruism and other components of the ‘help story’ in various forms, and they can and ought to gain employ. Upstanders are far more common than the mass media conveys, and social media can assist in bringing this forward.”.

Ultimately, stealth altruism is a “major challenge to the conventional narrative, which neglects the life-risking heroism and altruistic nobility of certain Jewish [and gentile] victims of Nazism.”

The professor’s research has had a negative response in some quarters. “Certain Holocaust educators insist my approach ‘muddies the water,’ diminishes the significance of the ‘horror story’, and exaggerates the significance of the ‘help story’. They champion instead time-honoured ‘horror centrism’. Certain Holocaust centre administrators and curators concur, as do also some elderly wealthy benefactors, or so I am told.”

But, he has also received a positive response “from certain young Holocaust scholars, progressive Holocaust centre administrators, and open-minded members of audiences I have addressed, along with many survivors long ago exasperated with horror centrism. I get particular encouragement from young adult Jews who want a view of the Holocaust that goes beyond the horror to note the inspiring care-sharing aspect.”