OpEds

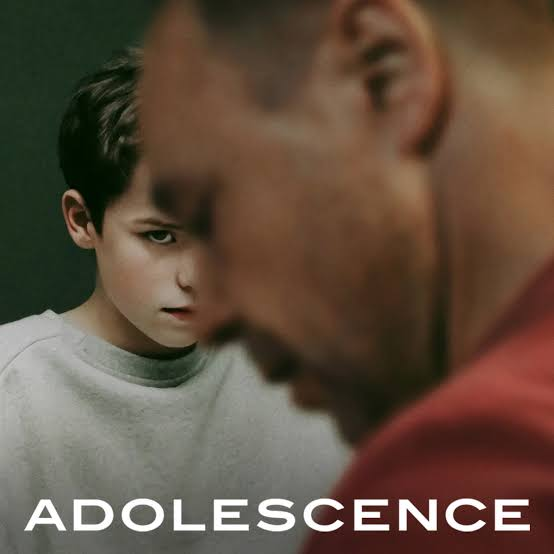

Adolescence brings teens’ plight to the attention of adults

Everyone is talking about Adolescence, the latest Netflix miniseries created by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham. And so they should be. This gripping four-part drama has sparked a widespread wake-up call by confronting an uncomfortable truth: do we really know what our children are being exposed to online? Are they really safely tucked up in their beds at night, or are they inviting in virtual guests who are dangerously shaping their identities, belief systems, and moral code?

The series opens with a shocking scene: on a quiet morning in West Yorkshire, 13-year-old Jamie Miller, played by Owen Cooper, is arrested for the murder of his classmate, Katie. The series turns the classic crime drama structure on its head by revealing the perpetrator in the first scene, forcing us to confront the unsettling question why. What unfolds is a chilling yet deeply human story of a boy failed by society, and a girl whose life is brutally cut short.

Adolescence shines a spotlight on the toxic expectation of masculinity being disseminated through social media. Online misogyny, bullying, and overstretched institutions emerge as the main culprits in a story that portrays abuse as a complex web of personal and systemic failures that entrap victims, perpetrators, their families, and entire communities.

Jamie is portrayed not as a monster, but as a lonely, bullied boy shaped by rejection, ridicule, and the toxic influence of online spaces. Labelled an “incel” (involuntary celibate) and humiliated by peers, his emotional wounds fester into rage. Adolescence exposes how emojis, slang, and private messages conceal a world of cruelty, desperation, and distorted perceptions of masculinity that are being spread in plain sight on our children’s social media feeds.

Jamie is also exposed to online misogynistic content and toxic forums that validate his anger. In an agonising scene, after being shoved by Katie during a confrontation, Jamie’s inner turmoil reaches boiling point, and he reacts with fatal force, leaving the viewer with no doubt as to his guilt while giving them a glimpse of his inner torment.

The series evokes an unsettling tension throughout, made more disturbing by the fact that Jamie’s parents aren’t monsters, but ordinary, caring people. This fact denies viewers the comfort of an easy answer, forcing them to sit with the more uncomfortable truth. Even in this caring household, Jamie’s silent suffering went unseen. At school, overwhelmed teachers miss the signs, while detectives and psychiatrists slowly realise how adults have misread the coded, emoji-laden world of teen communication, belatedly realising that Katie had been bullying Jamie by publicly insinuating on Instagram that he was an “incel”. Katie’s bullying, veiled in social media code, goes unrecognised until it’s too late. Online, Jamie absorbs toxic, misogynistic ideologies that equate respect with fear, turning a lonely, ignored boy into a killer.

The series brilliantly captures the storm of adolescence: the fluctuation between rage and vulnerability, arrogance and fragility. In scenes with child psychiatrist Briony, played by Erin Doherty, Jamie sheds his bravado and reveals a boy who just wants to be seen. When he screams, “Do you even like me?” it’s not a demand for affection, but a deep and sincere cry for validation.

Crucially, Adolescence refuses to excuse Jamie’s actions. Katie’s life, and the unthinkable grief left in her wake, are never minimised. Her parents, friends, and community are devastated, and the show holds space for their pain, refusing to let Jamie’s trauma negate the impact of his violence.

Still, the series highlights a painful truth: abuse is often a cycle. Jamie wasn’t born broken, he was shaped by ridicule, rejection, online toxicity, and a society that looked away. The Miller family’s heartbreak is clear in Jamie’s father’s stunned collapse into his son’s arms after seeing the video confirming Jamie’s guilt – a moment of shattered understanding and enduring love. Jamie’s sister, Lisa, offers a quiet contrast. Emotionally grounded and kind, she shows the family wasn’t inherently dysfunctional. It’s a stark reminder that violence can’t always be reduced to simplistic ideas of “bad homes” or “evil children”.

Yet, Adolescence offers glimmers of hope. Jamie begins to open up in therapy. Briony’s gentle persistence hints that healing, while slow and painful, is possible. The Miller family evaluate their new reality. They don’t abandon Jamie, but they do confront the hard truths of his actions.

The series has resonated beyond the screen. Legislators in the United Kingdom have referenced it in debates on online safety and violence against women. Advocacy groups are using it to push for stronger revenge porn legislation, echoing Katie’s experience of having a private image shared without consent. Schools are screening the series to start conversations about abuse, misogyny, and the silent suffering many teens endure.

For parents, Adolescence offers a sobering reminder that open dialogue isn’t optional, it’s essential. The message that “nothing is too terrible to tell me” and “no matter what” could be the difference between intervention and tragedy. For educators and policymakers, the series emphasises the need for awareness and intervention to prevent the escalation of online harassment into real-world violence.

As an anti-abuse organisation, this series offers us a springboard to engage our community about recognising early signs of abuse, the need for education on the dangers of the online world, and the addressing of toxic gender attitudes.

Ultimately, Adolescence is more than a drama. It’s a mirror held up to the failures of society today. It’s also a plea for empathy, responsibility, and action. The issues raised in this series are real, they are now, and they are costing us our children.

Unfortunately, Adolescence doesn’t give us the “sigh” of a happy ending. A child has been lost. Another has been ruined. And all around them are adults who are finally – too late – paying attention. But maybe, just maybe, someone will listen in time next time.

Because Adolescence doesn’t ask us to choose between victim and perpetrator, it begs us to protect both before it’s too late.

- Rozanne Sack is a co-founder of Koleinu SA, a helpline and advocacy organisation for victims of gender-based violence and child abuse in the Jewish and wider community.

Raoul

April 10, 2025 at 3:03 pm

I have not watched the series, but if ever there was a spoiler, this was it. Maybe next time, consider writing “Spoiler Alert” at the head of your article.

Alfreda Frantzen

April 10, 2025 at 7:24 pm

I’m sure this was not a “review” of a tv series – it was written to bring home the facts of teenage angst

Jessica

April 11, 2025 at 12:46 pm

Nope – “Adolescence” is just so typical of hidden antisemitic, anti-Israel and pro-Islamist propaganda perpetrated by auntie Beeb-like radical-leftist propagandists.

Making the antagonist a white boy is a dismal attempt to cover up the fact that the vast majority of rapes, torture and murders of white teen girls so far were and are still committed by Islamist grooming gangs.

No wonder Starmer and the rest of the pro-Islamist cabal love it so avidly. They’ve themselves been trying to cover up the Muslim rape gang scandal since it became news.