Parshot/Festivals

An unusual invitation to experiencing liberty

One of the better known, but on reflection, more unusual statements that we make at the Seder must be the opening paragraph of the Maggid section. In it we declare “Ha Lachma Anya – This is the bread of affliction which our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.” We then proceed to extend an invitation: “Let all who are hungry come and eat it.”

Rabbi Pini Hecht

Assistant Rabbi Green and Seapoint Hebrew Congregation.

What an unusual invitation! Is this the type of warmth and hospitality we are asked to extend? Inviting the hungry for a piece of dry cracker, the food of slaves?

Unusual as it may seem, this just might be the key to understanding the secret to freedom and liberty in our own lives. You see the Matzah at the Seder takes on another identity later on in the Haggadah. Whereas here we describe it as bread of affliction, we will later tell how this is the food our ancestors ate upon fleeing Egypt, thus becoming the bread of our freedom.

What transforms this ‘slave bread’ into the liberating substance it is later credited as? The secret I believe is in this unusual invitation: Nothing in life is more restrictive than living selfishly absorbed in one’s own pursuits and nothing is more liberating than opening oneself up to share with others. I can have little but live large by inviting others to share in what I have. This is the declaration we make at the beginning of our Seder, at the beginning of our own journey to personal freedom.

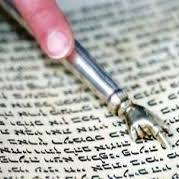

A look at the Hebrew letters that spell Matzah and Chometz reflect this same message. Just like the basic ingredients are virtually identical in each, so are the letters that make up the words. Both have the letters ‘mem’ and ‘tzadik’, they differ only in that Matzah is spelled with a hei, and Chametz, with a ches. Both these letters are shaped out of three lines; a horizontal line above and two vertical lines on either side. The only difference is that the ‘hei’ has a gap between the top of the left vertical line and the horizontal line above it and the ‘ches’ is closed completely on all three sides. Chametz is symbolic of a life lived closed to those around us, an individual selfishly absorbed in their own pursuits. Matzah with its open ‘hei’ represents a life of sharing, the opening through which we extend ourselves to help others and liberate our own consciousness.

Viktor Frankl said it best in his classic work ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’. In it he describes how sharing bread transformed individuals suffering in the worst of circumstances.

Frankl writes: “We who lived in concentration camps remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the freedom to choose one’s attitude in any circumstance.” Sharing the last of their food, these individuals expressed the inner freedom that no one can take away. It’s this same freedom we are expressing in our unusual invitation at the beginning of our Seder.