OpEds

Anyone can get the emoji picture

Last Sunday was World Emoji Day, but don’t panic: there’s still time to join in the fun. In fact, you probably already are, every hour of every day. It is estimated that 92% of internet users have used emojis, and up to 10 billion of these pictograms are sent every day in instant messaging, email and across social media.

No surprise there: they allow users to add instant emotion, tone and nuance to short messages. They represent a convenient shorthand, especially for those who often find themselves at a loss for words.

But emojis also represent serious business. Or, at least, serious impact on business. Various studies have shown that their use in marketing increases user engagement. Brands using emojis in their email subject lines achieve a higher email opening rate – and people process visuals dramatically faster than they do text.

According to Hubspot, emojis in a tweet can increase engagement by 25.4%, and in a Facebook post can increase the number of likes by 57% and the number of comments and shares by 33%.

The Unicode Consortium, the not-for-profit organisation responsible for digitising the world’s languages, says the most popular emoji last year was Tears of Joy (or 😂), which accounts for over 5% of all emoji use. The heart emoji (❤️) is a close second, then 🤣, with the rest of the top 10, following distantly behind, comprised of 👍 😭 🙏 😘 🥰 😍 and 😊.

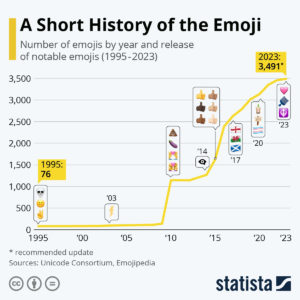

The original Unicode Standard comprised text and symbols that could be created by computers. Emojis formally became part of its ambit in 2009, but it had long embraced equivalents. Who remembers the wonderfully named Zapf Dingbats family of symbols? That was part of Unicode 1.0 in 1991.

Next year, the consortium will add to the existing 3 663 approved emojis another 31 new entrants, including the pink heart, the hair pick and the khanda, symbol of Sikh faith. That’s well down on last year’s 217 and this year’s 100 or so newcomers.

Ironically, while the number of objects that could be “emojified” may be infinite, the introduction of new entrants is fraught with cultural peril.

Says Jennifer Daniel, chair of the Unicode Emoji Subcommittee, “When there are as many foods as there are ingredients in the world, as many genders as there are people on the planet, and a variety of objects limited only by your imagination, every addition to the emoji palette is at risk of creating zones of exclusion without consciously trying.”

She makes the startling point that in some ways emojis were not intended to be for everyone. They were, in fact, a Japanese innovation, for people in Japan and exclusive to Japanese phone carriers.

“Reconciling emojis’ origins with where they are now — a worldwide phenomenon with a life of its own — is delicate. Everyone wants an emoji to be ‘mine’ when the truth is, they’re not. They’re everyone’s but also no one’s. Some 92% of the world’s online population uses emojis but what percentage of the world feels their identity is completely reflected in emojis?

“Should emojis be globally relevant or culturally specific? If they are for everyone, they should be as broad as possible. If they are intended for a specific group of people, then perhaps emojis shouldn’t be deployed on everyone’s keyboards.”

The challenge is even more delicate for keyboards that use non-Western alphabets.

“Like, what if the emoji selection for Hebrew keyboards were different than the emojis for Portuguese speakers, which would be different than the emojis found on Chinese keyboards? Nearly every culture has some form of dumpling but they all look radically different. As we lay the technical groundwork and strategy, these kinds of questions merit consideration. For now emojis are intended to be for everyone, which means encoding concepts that are as flexible as possible.”

Possibly the least known fact about emojis is that anyone can propose new ones. The 2023 roster, under the banner of Emoji 15.0, is done and dusted, and will be released in September this year. It can be expected to roll out on Android phones from October to December, followed by iPhones and social networks early next year. Cue a flood of the new shaking-head and high-five pictograms.

Submissions for the 2024 edition are still open, but you have only a week to get yours in – the closing date is 31 July. The Unicode Consortium provides extensive guidelines for proposed additions, in particular distinctiveness, frequency of expected use and “breaking new ground”.

Religious symbols are acceptable, but deities are not. The Star of David was approved as part of one of the early versions of Unicode, in 1993, and added to Emoji Version 1.0 in 2015. The menorah was approved as part of Unicode 8.0 in 2015 under the name “Menorah with Nine Branches”, and also added to Emoji 1.0 in 2015.

Marketers are out of luck here. Specific exclusions include logos, brands, signage, specific people, specific buildings and landmarks.

And even if your emoji concept is a winner, it won’t arrive on your neighbour’s phone tomorrow.

“It can take up to two years from conception and proposal to landing on your phone,” says Daniel.

Arthur Goldstuck is founder of World Wide Worx and editor-in-chief of Gadget.co.za. Follow him on Twitter on @art2gee