News

Cakes and canards: J. Lyons family story makes gripping reading

JORDAN MOSHE

Though this British giant is no more, its 150 year-long history features triumph, trauma, and perhaps almost predictably, a sprawling Jewish family at its heart. This is the story of Legacy, a captivating account of how Prussian Hebrew scholar Lehmann Glückstein and his family escaped the pogroms of Eastern Europe, made their way to London, and found themselves at the centre of one of the most powerful business empires in the world.

Written by acclaimed British author Thomas Harding (himself a descendant of Gluckstein on his mother’s side), it’s a story of tremendous success, shattering loss, and great deal of food in between.

“I grew up knowing my dad’s side of the family,” Harding told the SA Jewish Report last week. “They were German-Jewish refugees who came over in 1936. We spent most holidays with them and that was the family I knew. As for my mom’s side, I knew my grandparents and an uncle, but that was it.

“I have a vague memory of driving past various buildings in London as a child and being told that they were connected to our family.

“When I was about eight, my grandpa took me to one of the most famous spots, The Carvery. I was amazed by the plush red velvet chairs and the white starched linen tablecloths. The dessert trolley captivated me, piled with trifles, cakes, pies, puddings, and ice creams. My grandfather said I could have as much as I wanted. What he didn’t tell me was that he was the chairman of the company that owned the place and several others.”

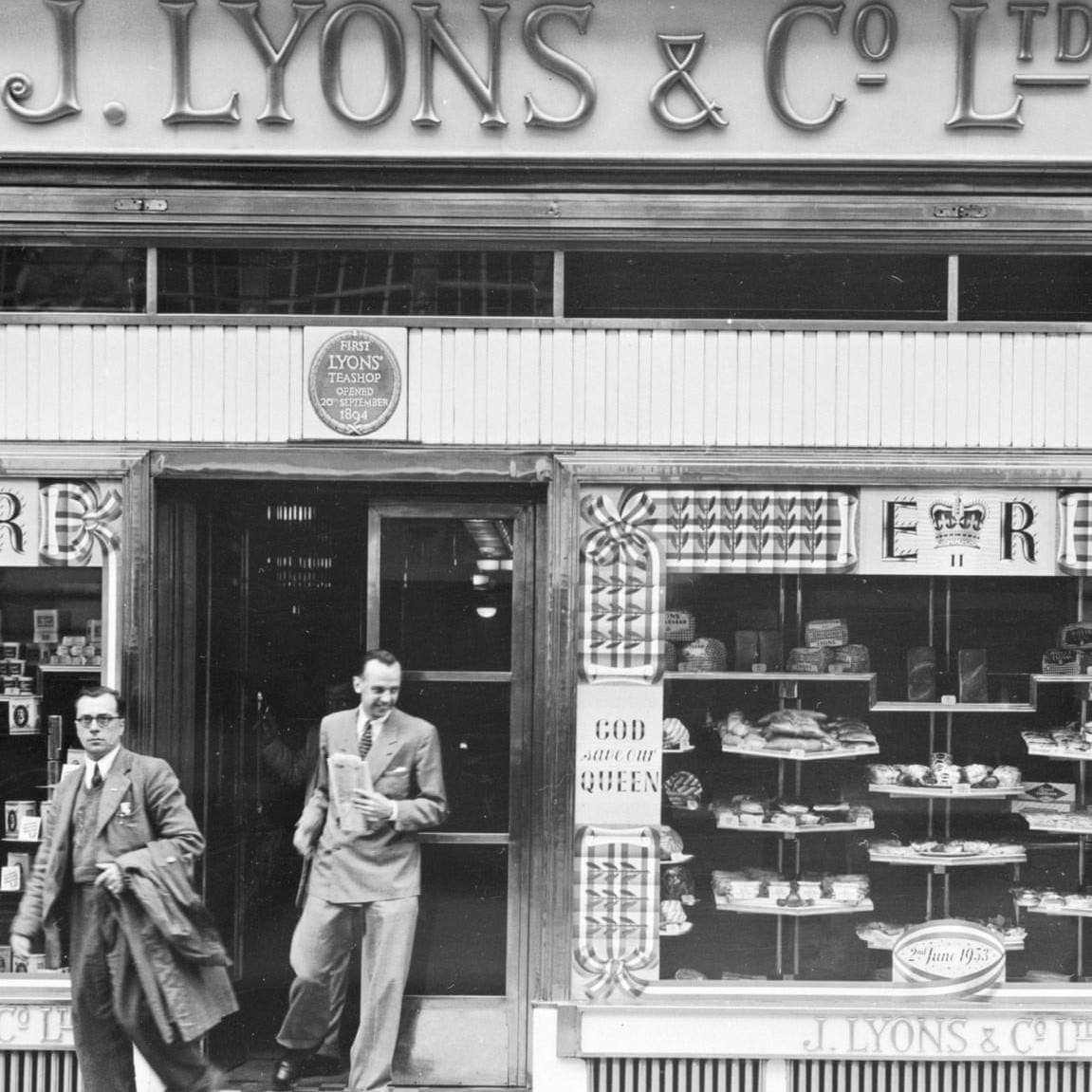

This empire had been forged from nothing. From the moment they arrived, Glückstein’s family took Victorian-era Britain by storm, growing a family tobacco shop into a chain and later partnering with impresario Joseph Lyons to form the iconic catering sensation. A multitude of tea shops, a variety of quality edibles, and a glut of entertainment spectacles characterised their growth across the decades, making Lyons a household name in a very short time.

“J. Lyons was a cultural phenomenon,” says Harding. “It employed millions, and created new work opportunities. It was the first space women could eat safely in public in the 19th century, and millions of people appreciated its products, from coffee to swiss roll.”

Even South Africa felt the impact of Lyons through the arrival of the Wimpy restaurant chain, a dining innovation piloted by the company.

“It had its faults, but it was extraordinary in terms of cost and quality,” says Harding. “This was a place for anyone, offering a good, reliable meal at an affordable price, and so much more.”

As a descendant of the acclaimed family, Harding set out in 2016 to capture this rich history to share it with the world.

“I was curious,” he says. “How did this enormous catering empire come about? Who was behind it? What can we learn about history through it?”

The journey introduced him to unheard of relatives, all of whom agreed that the time was right for such a project after years of anxiety and secrecy. With access to the family and state archives, Harding worked through a mass of letters, memoirs, family trees, and interviews to put his family’s story together.

Rather than feel overwhelmed, however, Harding was in his element. “Put me in an archive and I’m happy as Larry,” he laughs. “I love opening the doors of the past, and there as so many doors I can walk through. I like holding letters, talking to the people who remember what happened. For me, it’s total joy.”

His journey has given him glimpses into the lives of his ancestors, many of them unique personalities who were often all too human. Among these are Lehman’s grandson, Monte, and his sister, Lena.

“Monte was the Steve Jobs of the family,” says Harding. “He moved the family from tobacco into catering.

“Lena was a force of nature. She negotiated all the contracts, found the properties, and was prudent with money. She never bought new clothes for herself, even by the time they were all wealthy.”

Harding recounts an anecdote in which a family member apparently told Lena that she ought to replace the hat she often wore. “When she visited the milliner to replace it, however, he simply tuned it around and told her that she had been wearing it back to front. Seeing that the hat now looked different, Lena decided there was no need to buy another.”

Beyond the joy of watching historically accurate characters develop, Harding says that he also discovered much about his family that he (and even living relatives who had experienced the phenomenon themselves) never thought possible. This includes the fact that Lyons had been involved in making bombs for the British government during World War II.

“I had no idea,” laughs Harding. “They made cakes and Turkish Delight!

“But the fact is that they were experts in manufacturing. They knew how to make in bulk – on time, safely, and on budget. Making bombs isn’t really different from making chocolate cake. You have to follow a recipe. Obviously, there are safety issues involved, but they successfully set up a bomb factory, and by the end of the war, they produced one seventh of all bombs dropped on Germany.”

Central to the narrative is the family’s Jewish identity. Although they assimilated over time, their business success resulted in the recurrence of anti-Semitism throughout the family’s history, Harding says.

“The family was scared to share the story for a long time, and the anti-Semitism they experienced has a lot to do with it. Old canards about slippery Jews in business were common, and in each generation, they were accused of something.”

He continues, “Imagine you’ve been in a country for 100 years, you’ve become part of the establishment, your children are fighting in the army, and yet you’re still seen as an outsider. It’s upsetting and emotionally difficult, even for me.”

Still, the company went from strength to strength for decades, always at the forefront of innovation and service excellence. Sadly, however, Lyons didn’t survive Britain’s economic collapse of 1976, with the last of the tea shops closing in 1981. The loss was significant, says Harding, not just for Britain but for the wider business world.

“We lost a dynamism of innovation when Lyons closed,” he explains. “This was the first food laboratory in Europe, willing to experiment and fail until they succeeded. They were always considerate of the public, took care of their staff and promoted decency and fairness throughout their years of trading.”

The Lyons story can teach us many things, Harding concludes.

“Beyond family commitment, it shows us what we can gain from exploring our own personal histories,” he says. “We all have rocks to turn over, and while we may not always find good things underneath, what we discover can help us understand what makes our families what they are.”