SA

Canings and chaos at first Jewish hostel

The boys of Herber House refused to have their football confiscated without a fight. They grabbed makeshift drums and chanted slogans as they marched to protest this gross injustice and deprivation of liberty.

JORDAN MOSHE

Turns out, their ball, seized out of the overenthusiastic enforcement of Shabbat, was promptly returned, and the aspiring revolutionaries resumed their game.

This is a snapshot of life in the 1940s at Herber House, the first ever Johannesburg Jewish hostel for primary school children from country communities. It was the precursor to the King David Linksfield hostel.

The ball scenario is one of many meticulously collected by Stuart Buxbaum, himself a former boarder, who is researching the institution.

“I’ve never stopped being a Herber House boy,” says Buxbaum. “By researching the hostel’s history, I’m telling a story that needs to be told. It’s the story of rural Jewry of South Africa and its life experiences.”

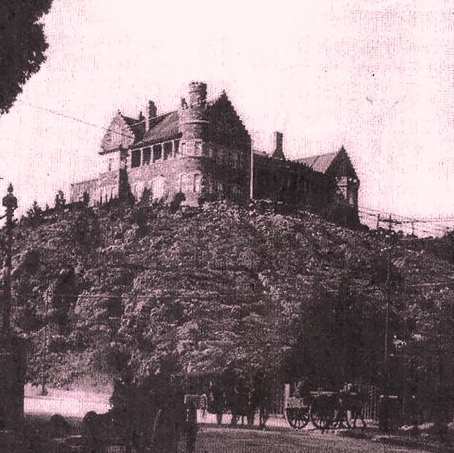

Herber House was originally Eastington Castle in Doornfontein, with cavernous interiors, soaring turrets, and stained-glass windows. The experiences of the then very young residents that Buxbaum collected were at times comical, at others horrendous.

Buxbaum, 71, was born and raised in Leslie, Mpumalanga. He arrived at Herber House in 1958 with his two sisters and spent seven years at the hostel until matriculating from King David school in 1965.

He consulted extensively with the former headmaster of King David Linksfield, Elliot Wolf, who arranged access to minutes of the South African Board of Jewish Education (SABJE) which was responsible for the hostel’s inception. He also got hold of the unpublished memoirs of Rabbi Philip Heilbrunn, another former boarder, to create a 45-page document which accounts for the history of the institution from its creation.

Buxbaum wanted to discover what kind of experience the children had at the hostel.

“There’s no doubt that there were good intentions from the beginning,” he says. “They wanted to create a model institution for Jewish youth. The people who planned it were noble, but they were hamstrung by circumstances.”

“The brand was good,” he says. “But it was tarnished by the people and reality on the ground. The committee was too high above everything, and people were unsuitable at lower levels.”

Eastington Castle wasn’t an entirely appropriate choice. The mansion was renamed in honour of Harry Herber, then chairperson of the board, but little else was changed. “It was as if [the board] hadn’t actually planned a hostel. It simply bought a castle, put in furniture, and moved children into it without planning sleeping arrangements.”

A gloomy interior full of nooks and crannies, the edifice was reportedly described as being “only fit for bats, bugs and bonfires”.

Add to the mix a terrifying matron and housemaster ill-suited to care for youngsters, and you can understand what these early years might have been like. Until today, the names of “Mrs Dubin” and “Mr Saltzman” strike fear in the hearts of those who experienced life under their care.

“The former was tyrannical, the latter temperamental,” says Buxbaum. “The mention of Mrs Dubin’s name can still make people turn white. She was strict and scary, and was often the cause of complaints of maltreatment.”

Rabbi Isaac Goss, the then assistant director of the board, said in a report at the time, “Mrs Dubin has done a good job of work, but she has a tendency to let her temper get the better of her. It must be made clear to her that she has to control her temper for the welfare of the institution.”

Equally terrifying was one of her assistants, a Mrs Bernstein, who was described as “a tough disciplinarian who would not stand for cheek from anyone. She could pull your ears in a most excruciating way.”

Two visitors, a Mrs Pollard and Dr M Mendelow, penned what they witnessed when they arrived at the hostel at 07:15 in February 1953. “The ban on conversation created a strained atmosphere. We found a pale little girl dressed, standing aimlessly. She appeared to be ill, and we were informed by the matron that she was still not well enough to attend school. In our opinion, there was no reason why she should have been out of bed.”

Heilbrunn, who attended the hostel between 1959 and 1963, wrote, “The masters were greatly skilled in wielding the cane and lorded it over us, as the Haggadah puts it, “with rigour”. Their great moment was at inspection around 18:00.

“One minute late got you one cut, two minutes, two cuts, and so on. Then, if your shoes were dirty, it was one extra cut, and if your hair was not neat or you were … guilty of some other infringement, it was again an extra lash with the cane. The next day on the bus to school we would compare our ‘war wounds’ and rank ourselves.”

Experiences varied, however. One boarder who arrived in the late 1940s told Buxbaum, “I thought I was in heaven when I arrived. To be among so many Jews! Look, I had been at boarding school in Kimberley, among all the gentiles. That wasn’t much fun.”

Buxbaum recalls the mixed emotions food would cause amongst the hostel’s youth. “There was once unhappiness with a particular serving of beef and vegetables at the evening meal. A boycott was called. It was my favourite dish of the week – it dripped with thick, greasy fat. The plates were set in front of us.

“Longingly, I looked at the roast slice, going hungry during those meals until it was removed from the menu. The kitchen supervisor had got the message.”

Over the years, there were numerous investigations into the living conditions of boarders. Facilities, living standards, and disciplinary measures were subjects of debate for years after its establishment.

Buxbaum says the boarders developed, quoting Heilbrunn, “a feral culture”, which manifested by “chutzpah being a trait greatly admired”.

Boarders found ways to stick it to the authorities, by nicknaming their housemaster and matron “Mr and Mrs Oog”. Saltzman would respond in kind by addressing the boarders as menuvels (a grossly insulting Yiddish word meaning vile or base).

The contestation between the parties would reach its height on Saturday evenings in shul. Says Buxbaum, “Tension was heightened. Many and varied had been the transgressions of the boarders all week long. We would be reproached as a group of miscreants.

“Silently the boys sat, a nudge-nudge here, a glance there, and a wink at each other. The dénouement came at the conclusion of the evening service. The new week would be ushered in with song. A blessed week! Shavua Tov! Little could those who generations ago had ushered in the week with this hopeful message imagine it being corrupted by a bunch of lads singing, ‘Shovel it off, shovel it off!’ with appropriate spade work. The housemaster’s reproaches had missed their target.”

A new hostel opened on the grounds of King David High School in 1966, and the sprawling mansion was sold and razed to the ground. Buxbaum matriculated in 1965, but says his experience at the hostel varied.

“It underwent a culture change,” he says. “People revitalised it, new blood came in, and it made for a different experience.”