News

Cape Town community shrinking – but not due to emigration

TALI FEINBERG

This is according to the newly-released final results of the Cape Town Jewish community survey, which was commissioned by the Cape Town Jewish community and conducted by the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Cape Town. Its methodology included extracting data from communal databases, focus groups, and 770 face-to-face interviews with a random sample.

The Jewish Community Survey of South Africa is another project of the Kaplan Centre. The results of this survey are expected to be released in March 2020.

The Cape Town survey estimated the affiliated Cape Town Jewish community to be about 14 000 members, just over half of which (53%) are female. It’s an ageing community, with a median age of 52.

The results show that between 2008 and 2017, there were 956 births and 2 311 deaths. This signifies a net natural population decline of 1 355 people over the period, or the loss of 136 people a year. A comparison of annual birth and death rates indicates that, excluding emigration and ‘’semigration”, the Cape Town community has entered a phase of net natural population decline, says Kaplan Centre Director Adam Mendelsohn.

Between 2002 and 2006, there was an average of 64 Orthodox marriages a year, declining to about 40 per year for the period 2013 to 2017. Annual birth rates have declined from an average of 111 births a year between 2005 and 2010, to 91 a year between 2012 and 2017. Moreover, the number of births further declined to 77 in 2016 and 75 in 2017.

Compared to that data, emigration appears to be less of a threat. Seventy to eighty percent of Cape Town’s Jewish students have attended Herzlia since the 1960s, and 56% of those graduates still live in South Africa. Only about 44% of all Herzlia graduates have emigrated: 13% are living in the United States, 9% in Australia, 9% in Israel, 8% in the United Kingdom, and only 3% in Canada.

While 71% of people over the age of 70 have at least one child living overseas, only 14% have all their children living overseas, and 43% have all their children living in South Africa.

About 21% respondents of the survey are single, 58% are married, 11% are divorced, and 10% are widowed. Intermarriage remains low – only 11% of those who are currently married have a non-Jewish partner. The majority of respondents (76% overall) consider it to be important that their children are Jewish.

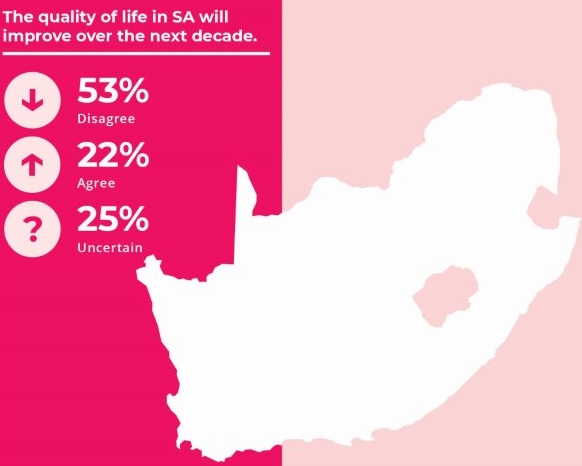

The survey certainly captured a moment of pessimism and uncertainty, says Mendelsohn, with 53% of community members disagreeing that quality of life will improve in South Africa over the next decade, and 25% being uncertain. Within this context, youth are relatively more optimistic about the future, with 38% of the youngest group agreeing that quality of life in South Africa will improve. At the same time, an element of financial vulnerability exists amongst older community members. Of those aged 70 years and older, 34% are just making ends meet, 35% have no retirement savings, and 20% don’t own their home.

“The results underline the community’s strong communal identity, with more than seven out of ten community members feeling connected to Cape Town communal life. The community has a strong emotional attachment to Israel, with about 90% feeling very or slightly attached. Furthermore, a Jewish education is the norm for the Cape Town community,” writes Mendelsohn. “Emblematic of the community’s sense of communal identity, 79% of respondents report that someone in their household has donated to a Jewish cause within the past 12 months.’’

When self-identifying into one of a number of descriptive categories, 65% of respondents described themselves as either “traditional” or “secularly/culturally Jewish’’. This manifests in religious practice, where 9% don’t drive on Shabbat, and 15% eat only kosher meat when outside the home. However, 91% and 96% of respondents regularly participate in Shabbat suppers and Pesach Seders, respectively, and 78% refrain from eating pork.

“While anti-Semitism is perceived to have increased, participants lead an openly Jewish life. Cape Town community members very rarely opt-out of synagogue services or communal events. Specifically, 2% frequently/occasionally avoid synagogue amid safety concerns, while 6% frequently/occasionally miss communal events for the same reason. In contrast, larger proportions don’t want to be publicly recognised as Jewish or Zionist. Specifically, nearly 30% avoid wearing Jewish apparel in public amid safety concerns, and about 40% avoid wearing Zionist apparel,” says Mendelsohn.

In terms of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the majority of respondents (64%) believe that, while there has been fault on all sides, on balance, Israel is in the right. A further 12% believe that Israel is completely in the right in all its actions.

When it comes to criticising Israeli government policy, 84% of respondents agree it’s acceptable to be critical in Jewish communal spaces. By contrast, 43% consider it acceptable to be critical of Israeli policy in public (beyond the community). There is a strong age narrative, with the youngest age group being more accepting of public criticism of Israeli policy. For example, about seven out of ten 16 to 29-year-olds agree that South African Jews should be free to criticise Israeli policy in public, decreasing consistently to a low of 30% for the oldest age group.

The average household unit is small, with 2.6 individuals per household. This is comparable to the 2005 Kaplan Study which found an average number per household of 2.9 nationally and 2.8 for Cape Town.

The community is extremely well educated, in terms of South African and global standards. Of those aged 22+ years, 54% have obtained tertiary-level education, 22% have completed a bachelor’s degree, 19% have a postgraduate degree, and 13% have a professional qualification. This is compared to broader South Africa, where 4.1% of those aged 22+ have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

In terms of employment, of those aged 22 years and above, 36% are self-employed, 30% are in full-time employment, 10% are employed part-time, and 1% are unemployed.

The Cape Town community places great importance on burial in a Jewish cemetery. When asked about the importance of a Jewish burial, 86% indicated that it’s important to be buried in a Jewish cemetery (with 76% considering it to be very important).

Mendelsohn says that the data demonstrates dynamism – a population with a strong sense of connection, nurtured by an abundance of communal organisations – and challenges in the present and future.

“Some of these challenges reflect the particular timing of the study – the buffeting effects of crises at Eskom and with Cape Town’s water supply; and dispiriting revelations from the Zondo Commission’s investigation into corruption,’’ Mendelsohn says. “But others reflect issues internal to the Jewish community including an ageing population and concern about the depleting effects of emigration. This study is intended as a step toward identifying and building on the strengths of the community, as well as preparing to meet these challenges.”