Holocaust

Chance meeting changes life of Holocaust survivor’s daughter

While award-winning writer Gina Roitman was trying to help other daughters of Holocaust survivors to deal with their trauma, she found solace and understanding in meeting the daughter of a woman from her own mother’s past.

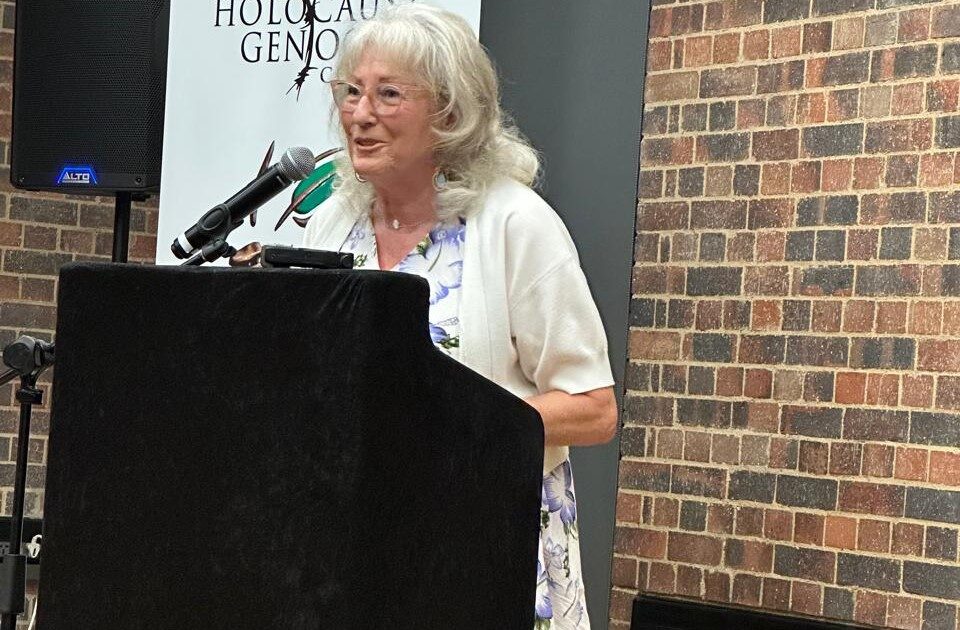

In August 2020, Tammy Lerner approached Roitman, also a biographer, writing coach, and daughter of a Holocaust survivor, after attending a webinar discussing midwives in displaced persons (DP) camps. Lerner realised there were similarities in their histories. Roitman told an audience at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre on 31 October that this interaction with Lerner “would change my life and put a new perspective on the story I now tell”.

Roitman had been holding memoir workshops for daughters of Holocaust survivors where they could share their stories and find catharsis, and it was through this that Lerner heard about her and contacted her. “Tammy’s email delivered the opportunity to uncover a long-lost piece of my history, the incredible trials of my mother’s life,” Roitman said.

She said that she and Lerner had actually met briefly before on a trip to Israel when Roitman was 18, but neither was very interested in finding out more about their parents’ history. “That trip was decades before I realised how many questions I had failed to ask. Tammy’s email delivered the opportunity to uncover a piece of my history.”

Following the email, Roitman and Lerner were able to piece together the parts of their stories they had gleaned throughout their lives, and both emerged with a larger story of how their families had survived the horrors of the Holocaust.

They worked out that their mothers had both been living in Czerniów in southeast Poland, and both were newly married before the war began. Roitman said her mother, her mother’s first husband, and Lerner’s mother and father and another couple had been best friends before the war. When the Nazis invaded Poland, the three couples decided to flee to Soviet-occupied Poland, but weren’t able to settle there.

“The Soviets forced Jews and other undesirables onto trains and transported them east along the route of the Trans-Siberian Railway. The three couples were separated and dropped off at different locations. During those terrible war years, there was no way to maintain contact,” Roitman said.

Her own mother never revealed where she landed up, only that it was somewhere in Central Asia, where the winters were freezing and the summers boiling. “When it was asked where she had been between 1941 and 1944, all she could offer was a question mark,” said Roitman.

Roitman’s mother gave birth to a son, Yitzchak, just after losing her first husband to malaria. Yitzchak died of starvation when he was only three years old.

Lerner’s parents were deported to labour camps, and when the war was over, they went around the camps looking for Polish Jews in the hope of finding their friends from before the war.

“This is where Tammy told me that they found my mother, emaciated,” said Roitman, “They nursed her back to health, and in 1945, took her with them to their home town, Czerniów, 20km northeast of Auschwitz. My mother was hoping to find at least one of her five sisters, only to learn that they and her parents were dead.”

Roitman said that her mother and Lerner’s parents ended up in the Pocking-Waldstadt DP camp governed by the Americans. While there, Roitman’s parents would meet, and she would be born in a hospital near the camp in January 1948.

Both families would separate again, emigrating to different countries – Roitman and her family to Canada, and Lerner’s to Israel.

Roitman told how her childhood had been filled with stories from her mother’s past and her best friends, but up until reconnecting with Lerner, “there were always only stories. There was one more gift Tammy offered me, a photo of the three friends taken in 1933 when my mother was 20 years old. She is smiling and warm, something that no photo of her younger self ever revealed in all those photographs she carried from Poland to Canada.”

Roitman told her mother’s story and the story of her birth in Passau in her 2013 documentary, My Mother, The Nazi Midwife and Me.

“Every year, on my birthday, mama woke me with the account of how she had saved my life by ensuring I wasn’t born in the DP camp but in a proper hospital in the nearby town of Passau, the town, incidentally, where Hitler spent his formative years,” said Roitman. “The reason I was born in Passau was because she had heard rumours about babies dying from a murderous midwife.”

In 2006, Roitman went on a mission to Passau to find out more about the tale her mother had been telling for 28 years. “On this trip, I learned that my mother’s story was true. She wasn’t the paranoid Holocaust survivor I had always thought. There had been too many baby deaths. A murderous midwife who, after the war, was still intent on ridding the world of Jews by killing newborns. She would press on the baby’s fontanelle, that soft spot in the skull, which caused death within a week, and traumatised mothers who blamed themselves. The camp, under the jurisdiction of the American Army, was eventually forced to acknowledge that there was a disproportionate number of deaths. They exhumed the bodies of the 52 babies. All had died in the same way.”

Roitman said being able to tell her and her mother’s story enabled her to connect with many other children of survivors, and made her feel like no-one was alone in this world.

She said, “From Washington DC to Phoenix, Arizona, and on to Johannesburg, South Africa, then to me in Saint-Colombia, Quebec, there are lines stretched around the world and gathered in stories that have been interred for decades.”

Elisa Montecalvo

November 28, 2024 at 3:38 am

Gina, I’m so thrilled for you that you found pieces of your lost history. Seeing a picture of your mom when she was happy and innocent to the tragedies of the Holocaust must be priceless. It’s like winning a trophy. You’ll forever hold on to these cherished memories close to your heart. Be happy and take care ❣️ Your story is so touching, it will bring joy to many daughters who only know about the horrors of the Holocaust. Thanks for sharing your story!