Community

COVID-19 chaos leaves us breathless five years on

Do you remember when you weren’t allowed to leave your home except to buy essentials and you could do so only between certain hours? Do you remember fearing interaction with people one-on-one lest they made you fatally ill? Do you recall waiting for that phone call to hear that someone you love had contracted the killer virus?

It has been just five years since we embarked on the dreaded COVID-19 pandemic journey that brought death and destruction in its wake, killing more than seven million people around the world. The South African Jewish community was hard hit, and for some, those days are easier to forget than others.

Capetonian musician Ryan Lipman, 24, will never forget fighting for his life when he was on a ventilator in the intensive care unit (ICU) in Milnerton Mediclinic Hospital for two weeks.

“I thought COVID-19 would be a temporary setback, a few days of rest, some mild discomfort, maybe a loss of taste and smell,” said Lipman. “Instead, I ended up in ICU, struggling for every breath, surrounded by machines keeping me alive.”

Looking back, he said, “One of the hardest parts is explaining to others what it was really like. When people say, ‘Oh yeah, I had COVID-19 too,’ I don’t always know how to respond. There’s a difference between being sick at home for a week and fighting for your life in an ICU. It’s not about comparing experiences, it’s just that unless you’ve been there, it’s impossible to understand fully. That can feel isolating at times.”

He finds himself aware of behaviour that never bothered him before. “I notice how often people wash their hands, who’s coughing nearby. It’s not fear, just awareness, a quiet but constant voice in the back of my mind reminding me of what I went through,” he told the SA Jewish Report.

“Some days, I still struggle with the weight of what happened. But I choose to move forward with resilience, gratitude, and the knowledge that even in my weakest moments, I fought to keep going.”

Nicola Date, who is in her mid-30s and works in the digital design industry, says she also still feels the effects of having survived three bouts of the virus. “I’m quite a resilient person, but I will say that it had an impact on my relationship with touching other people physically. I’ve created a barrier between myself and other people. There has been a psychological reaction to getting sick from other humans on such a great scale.”

Her health also took a toll as her body fought off the virus three times. Date’s lung capacity hasn’t returned to what it was before, and she has “some damage to her eyes”, potentially related to blood clotting the second time she contracted the virus. “I was fit before COVID-19,” she said. ”I was a regular runner, and since COVID-19, my lungs have definitely taken a knock. I went from a fit runner to struggling with oxygen deprivation.

“I’m on a journey where I focus on my health and life because of the way it was impacted by COVID-19,” she says. The pandemic didn’t only have an impact on her health, her career in the creative arts also suffered from the lockdown.

However, Date, who had been an arts manager, comedian, and costume designer, had to survive, and so found her way to digital design. “It was an interesting journey because I took on a whole new career path because of the pandemic as the arts didn’t exist,” she said.

For those in the medical field whose lives turned into facing death on a daily basis, the nightmares are hard to stem.

“COVID-19 just signifies death to me,” said pulmonologist Dr Anton Meyberg, who believes that though professionals didn’t do what they did for acknowledgement, there was a lack of support and recognition of doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists who worked tirelessly in hospitals to save lives.

At the time, everybody else got to be home with their families. My family was kept at home without their father, without their husband, because I was in the hospital almost 24 hours a day every single day,” Meyberg said.

“We used to shower at work about nine times a day, even with PPE [personal protective equipment] and then come home and take off our clothes before we went inside in the fear that we would, G-d forbid, bring [COVID-19] home to our families, even with all those measures in place,” Meyberg said.

“It was stressful and psychologically draining. Patients never got to say goodbye to their family members. We had 40-year-old people who would write their will on their cellphone before we’d put them on a ventilator, and they never made it,” he says.

When he thinks back to those days, he responds with “PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder],” he said. The trauma experienced by medical staff, who were “the last port of call for the [patients’] families from a spiritual and physical level and witnessed multiple deaths a day” took a devastating toll on their well-being.

For Hatzolah responders, taking people with COVID-19 to hospital and not knowing whether they would see their families again, was heartbreaking. Because of this, said Operational Manager Uriel Rosen, we “had to change Hatzolah protocols that in our wildest dreams we would never think to change”.

They had to allow family members to say goodbye to their loved ones before going to hospital, irrespective of how ill the person was just in case they never returned, and in many cases, they didn’t, he told the SA Jewish Report.

“For critically ill patients, we used to sit in the back of the ambulance and say vidui – the confession prayer before someone dies – with them while they were still able to talk,” Rosen said. In the peak of the virus, “the demand for oxygen concentrators was so high”, Hatzolah had no choice but to ask families still sitting shiva for the oxygen machine their deceased loved one had been using because someone else urgently needed it. “It took a big toll on those calling. No-one wanted to do that. They wanted to let people grieve.

“We used to take COVID-19-positive patients to their families’ funerals isolated in our ambulances and remaining on oxygen,” Rosen said.

Hatzolah managed to retain some positives from the virus era. “A lot of projects have been launched from the COVID-19 wellness programme. We learned that you can do a lot by just calling someone, such as our mom’s programme, which is for postnatal depression.”

Jewish communal leaders jumped into action before COVID-19 had entrenched itself in the country. “We set up a committee – including experts like Professor Barry Schoub and Dr Richard Friedland – that basically saved South African Jewry from a total catastrophe,” said Zev Krengel, the national president of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies.

Krengel said the committee put in place protocols and policies dealing with schools, shuls, communal events, and other gatherings to ensure the community’s safety. In so doing, he said, it managed to prevent “major superspreading events, like what had happened elsewhere in the world, especially over Purim that year”.

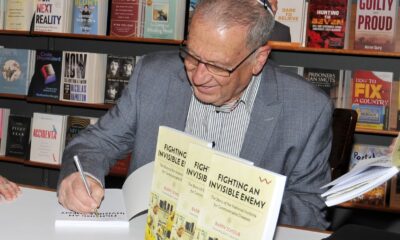

Schoub, who also landed up chairing the South African national ministerial advisory committee on vaccines, said that at the beginning of the chaos, “I’d actually retired, and we were about to go on holiday when I got an urgent call from Zev.” The committee functioned for two years to protect the community.