News

Cutting edge brain surgery may help make you ‘un-sad’

JORDAN MOSHE

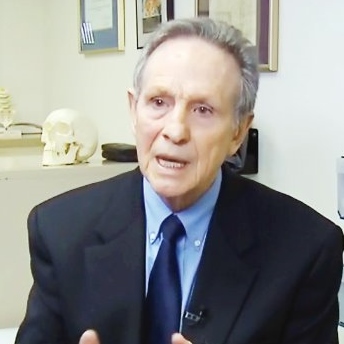

This South African expat believes he has identified the centre of sadness in the human brain, and, using a specialised surgical technique, is helping to solve debilitating biological depression.

Through an operation he pioneered, Hurwitz believes he can make people “un-sad”. “Basically, the surgeon cuts through the cabling system in the brain and interrupts the transmission,” he says. “We intercept the circuits responsible for emotion. The assumption is that these pathways carry the circuits that are causing disabling depression.”

In the past 20 years, Hurwitz has seen 17 patients undergo the procedure, 12 of them suffering from depression, and has had incredibly positive results.

His findings are nothing short of miraculous. “They have told me they aren’t sad nor suicidal,” he recounts. “I’ve seen this in 12 cases. Their sadness vanishes. These were patients I’d known for many years – they’d overdosed, been suicidal, gone through shock therapy, and yet in an interview after surgery, described a different feeling altogether.”

But before it can be seen as a solution, it has to be validated 100% by medical science. Until then, it remains experimental. “Neuroscience is going to take this idea and take it apart – that’s its job. If it’s validated, we will have found out a new truth about the human brain, Hurwitz says.

“Depressive illness is the second most prominent psychiatric illness there is, second only to anxiety. At any time, 5% of people around you are depressed. In a single lifetime, 10% of people will have a depressive episode.”

Hurwitz is the founder of the neuropsychiatry programme in Vancouver, Canada, which he has run for the past 30 years. He is the medical director of the programme, operating out of the University of British Columbia and specialising in bringing together neurology and psychiatry.

“The principle is to bring the [physical] brain back into the mind,” he says. “They are not separate entities. Everything in the mind is part of the brain structure, and they need to be treated together.

“Psychiatry deals with the fact that you cannot treat a patient as if they are just a brain. That would be a mistake. But equally, you cannot miss the brain when you focus on the mind. The mind is a component of the brain.”

He likens groups of brain cells to computer chips, each of them responsible for controlling a certain part of our everyday function. “From the cell group, you can trace the wiring that goes through the brain into the stem, the spinal cord, connects to certain nerves and muscles, and makes you move. Equally, when you think, feel, get angry, or cry – neurology is responsible for it.”

Medical science knows where the centres of various emotions are in the brain, including anxiety, anger and pleasure, according to Hurwitz. However, nobody has been able to identify the centre of sadness. “It has been very difficult to study,” he says. “The paradigm of sadness is major depression, and it can be used to attempt to locate the seat of sadness.

“When people see someone who is depressed, they think he can snap out of it. They tell him about all the good things he has in life, that he needs to get it together. The truth is that it’s a disease. Once you get depression, you have it for life. The pain of depression is so great for some that their only escape is death.”

Hurwitz says that the first port of call in such cases is typically drug therapy, partnered with intensive psychotherapy. “A good psychiatrist doesn’t treat a brain, he treats a person,” Hurwitz says. “Drug therapy can help, but it needs to be paired with therapy. You cannot treat a person as a brain. There’s a human there.”

However, some people don’t respond to antidepressants, and the next step is electric convulsive therapy involving anaesthesia and an induced seizure. In certain cases, not even this alleviates the symptoms. This has led to the option of surgery.

“In the old days, this was the frontal lobotomy,” he says. “There was no alternative. A lobotomy solved a problem, but created zombified people by separating the front of the brain from the back, the mind from motor control. It helped, but it was catastrophic.

“However, in the modern era, people have realised that there are circuits and wiring in the brain. If we interrupt these, we can change something.”

Starting in 2000, he devised surgery known as an anterior capsulotomy, a form of brain surgery far more sophisticated than the chilling procedures of the lobotomy days.

The procedure itself involves the screwing of a frame to the skull while one is awake, and using an MRI, X and Y co-ordinates are plotted and a very specific point identified. Two holes the size of 50 cent pieces are made in the skull, and metal probes are inserted through brain tissue. The tips of the probes are heated to 60 degrees for 60 seconds, burning a rectangular lesion and killing the tissue.

The low number of patients who have undergone this operation is explained by the fact that the surgery is a last resort, used only in cases of people who are going to end their lives, and after intensive medical and legal processes are carried out.

Says Hurwitz: “Patients see me for a first opinion, then a colleague for a second opinion. They then see two other psychiatrists for consent, and then a neurosurgeon. All five send through reports to a lawyer, who meets with the patient to make sure he is aware of what he is going to undergo. A committee then convenes to review the process and accept a patient. In 20 years, only 17 people have been approved. You can’t just cut through the brain.”

Hurwitz himself sees patients immediately after surgery as a psychiatrist, not a surgeon. “From a neurosurgeon’s perspective, if you can stand up and walk after surgery, you’re doing well,” he says. “I need to see how you’re feeling post-surgery. For the first two weeks, a person thinks they’re on Mars. After the swelling recedes, I can ask how they feel. They can then tell me how they feel inside.

“This surgery makes them instantly un-sad. There’s no term in psychiatry for it.”