Featured Item

Did the Exodus really happen, and does it matter?

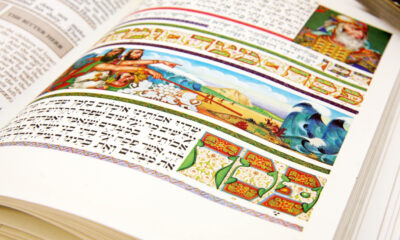

Every year on Pesach, Jewish families around the world faithfully gather to tell the story of the Exodus, when Moses led the Israelite slaves out of Egypt. The haggadah is rich in experiential learning, recounting this foundational legend of Jewish liberation through food, stories, and songs. We recall the Exodus each Shabbat, and every Jew is commanded to see himself or herself as having personally left Egypt. We’re commanded to pass the tale on to future generations. But how historically accurate is the Exodus story? Is there corroborating archaeological evidence? And does it really matter?

If one considers the Torah to be the unchanging, unchallengeable word of G-d, there’s no debate. The Exodus is a central article of faith, and is taken as being literally true. But if one sees the Tanach as a series of books written by different people over time, does the Exodus stand up to scrutiny?

Sceptics argue that there’s no hard evidence that the Israelites were enslaved in Egypt in the first place. They point to the fact that the Egyptians – meticulous chroniclers of their leaders’ lives – make no reference to the enslavement or the Exodus in writing. They also note that there’s nothing to show a dramatic population loss that would have been experienced if large numbers of Israelites suddenly left Egypt, as the Torah claims.

Rabbi Ramon Widmonte, the dean of the Academy of Jewish Thought and Learning, said, “The question is what type of archaeological evidence is there for anything at all in history, and what would one expect there to be for an event like this?” Officials always seek to promote their own narratives. “Egyptian kings aren’t going to record a defeat – they never record defeats. You’re never going to get Egyptian records of their big defeat – it doesn’t exist. What do you expect to get, and where would you get it from? What type of evidence is likely to have survived from that time period? Who would have recorded it?”

Archaeological evidence is, indeed, rather thin. Supporters of the Exodus story point to the Merneptah Stele, a victory monument built in the 13th century BCE by Pharoah Merneptah. It references “Israel” as a group defeated by the Pharaoh. Archaeological digs at Tell-el-Dabah and Kadesh Barnea reveal evidence of Semitic languages being spoken in Egypt at around the period of the Exodus, but this doesn’t mean that substantial numbers quit Egypt at that time. The Ipuwer Papyrus, which describes disaster befalling Egypt around 1 250 BCE, hasn’t received scholarly support as reliable evidence of the Exodus.

Rabbi Gabi Bookatz from Waverley Shul said there was no clear collaboration of the Exodus story, “But that’s not surprising. History is recorded by the victors, and the Egyptians weren’t going to record that. Even in the Six-Day War of 1967, the Egyptians denied the military disaster to their own people. We shouldn’t really expect to see much evidence.” He noted that Kenneth Kitchen, an esteemed British professor of Egyptology and archaeology, argued that as we move closer in the historical record to contemporary times, the more physical evidence there is for biblical events.

“Every year before Pesach,” said Rabbi Greg Alexander of the Cape Town Progressive Jewish Congregation, “someone sends out a photo of an Egyptian chariot wheel found on the floor of the Red Sea, or a thesis about how the ten plagues were really a result of extreme weather conditions, and I feel like they missed the point. When we read the Exodus, we get to see through the lens of our ancestors 3 500 years ago, how they transitioned from the complex family/tribe of Genesis to the nation that walked out of Egypt via Sinai to the promised land. It’s the greatest story ever told, of the oppressed being freed, the founding of a society based on morality, respect, and justice and it’s one that resonates in all cultures today.”

Alexander said that those publicly questioning the veracity of the Exodus often have a political motive, such as anti-Zionism.

“With the 21st century tools of post-modernism, we know that the text is created by the reader and reflects their interests and prejudices as much as the writer’s. Today, we find meaning in the message that has come to us from Sinai via a chain of tradition. This is moving, inspirational Torah teaching, and not a history or archaeology lesson. What matters isn’t whether it’s Rameses I or II, but how the study of Torah impacts us,” Alexander said.

And that’s the important thing to remember as we remember the Exodus.