Featured Item

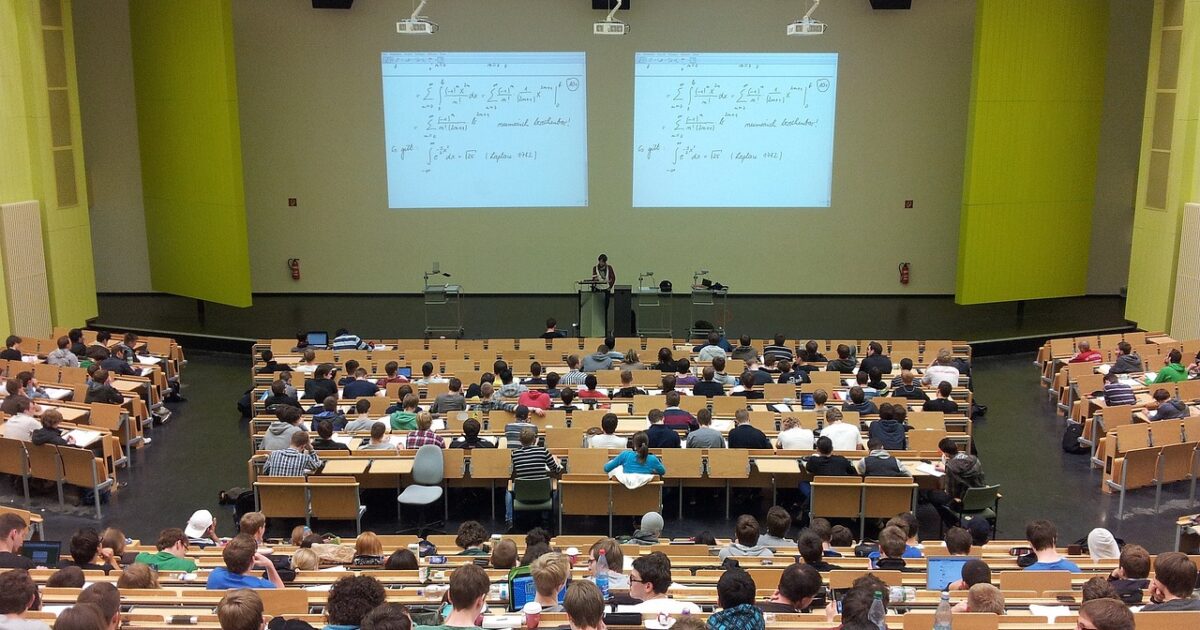

Disability units break learning barriers at university

Students facing learning, visual, or hearing challenges once felt ill-equipped to meet university requirements, but this is no longer the case because of the disability services offered by South African tertiary institutions.

Born profoundly hearing impaired, Dr Carolyn Fedler, didn’t have any learning support when she completed her BSc degree cum laude majoring in genetics and microbiology, or when she was later accepted to medical school. As a child, she was under the care of a speech therapist, who taught her to speak over many years of intensive therapy after school.

03/09/2023

Jewish Achievers Award 2023

“She didn’t want hearing-impaired children to depend only on sign language as she felt it would prevent them from having the same opportunities as any other hearing person,” Fedler says. As such, she encouraged Fedler’s parents to enrol her in mainstream schooling, which she received at King David Linksfield, then the only school allowing the integration of hearing-impaired children with normal hearing children. With hard work, minimal play, and extra lessons, Fedler matriculated with two distinctions.

On applying for a medical degree after matric, Fedler was told first to prove her ability to cope with university studies in general, so she began her BSc degree in 1983. After graduating and working in medical research for two years, she reapplied for medicine, and was immediately accepted. She graduated in 1994.

“There was absolutely no support available for students with disabilities, so I had to become resourceful,” she says. “I got help from my fellow students. I’d copy their notes and ask them to explain what the lecturer was saying if I couldn’t understand it. I made it work, but I had to work much harder than most people, and I did a lot of extra reading to catch up.”

Encountering a professor who constantly questioned her abilities, she proved him wrong by picking up a clinical sign in a patient that more senior doctors had missed. Her impairment in fact heightened her deductive thinking skills, setting her apart.

“Looking back, I can’t believe how I put up with such resistance,” says Fedler. “I don’t know where that perseverance came from, I just knew I wanted to do medicine, and there was no reason why I couldn’t.” Today a senior pathologist at Ampath, Fedler says that had there been more support for students like her, her journey would probably have been a lot easier. Yet perhaps she wouldn’t have learned to be so resourceful.

Today, South Africa’s university landscape has changed. In meeting transformation goals, tertiary institutions have a fairly uniform offering when it comes to disability services. Such services not only cater to students with physical disabilities but also to those with hearing and visual disabilities, learning disorders, and mental health conditions.

“Many universities tend to specialise in the disabilities their surrounding feeder schools focus on,” says Juan Erwee, senior disability officer and acting head of the University of Pretoria’s (UP’s) Disability Unit. For example, in Pretoria there are many schools for students with visual disabilities.

“Across universities, there’s an even spread of students with learning or neurodevelopmental disabilities,” he says. “This constitutes more than half of the students that we support. We take every student on a case-by-case basis, and offer tailored support.”

Criteria for disability support include a report from the therapist treating the student, fairly standard across institutions. With learning impairments, a battery of tests are also required. “If the student is taking medication or has any other treatment that mitigates the impact of the disability, they wouldn’t necessarily qualify because that would offer them an unfair advantage,” Erwee says.

“Students shouldn’t think of a disability as something that defines them,” says Erwee, who is blind himself. “You might need to do things a bit more creatively or find a slightly different path to reaching your goals, but it’s by no means impossible.”

Third year Bachelor of Arts in Psychology student Tamir Lipschitz, who heads up the South African Union of Jewish Students at UP, benefits from the university’s Disability Unit. “I have Tourette’s Syndrome, which means I can’t really write properly because of certain tics in my hands that cause twitches every few seconds,” he says. “Interestingly, typing isn’t affected as much.”

“I also sometimes struggle to compute words when I’m reading them. The Disability Unit has accommodated me by giving me a typing concession and granting me 10 minutes of extra time per hour in tests and exams – double what they granted me in school under the Independent Examinations Board.”

Lipschitz was called in by teachers at school to read out his tests, something universities won’t do, and he says lecturers cannot read his writing. “I don’t think I would have even made it through first year without this typing concession,” he says. “Maybe it’s a bit hyperbolic, but in a way, my future depends on it.”

Through its Disability Service, the University of Cape Town (UCT), also offers well-rounded support. This includes real-time text transcription; sign language interpretation; material for visually-impaired students; audio transcripts; scribes; practical laboratory assistants; and exam and test writing support.

“UCT is committed to working towards the creation of a discrimination free and inclusive environment which encourages disabled students’ full, independent, and effective participation in the mainstream of university life,” says UCT spokesperson Elijah Moholola. “Support for students with a wide variety of disabilities has continued to increase.”

Any student with any disability can approach the Disability Service for support, he says. “Disability encompasses persons who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

At the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), the Disability Rights Unit (DRU) aims to provide such students with the best learning experience possible by offering services such as sign language interpreting; real-time captioning; conversion of course material into accessible formats; IT training in various assistive technology; as well as access to dedicated computer centres. “The DRU also offers support with regards to neurodiversity and specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia,” says Duncan Yates, neurodiversity and mental health co-ordinator at the DRU.

“DRU’s focus is to help integrate students with disabilities into the academic sector, ultimately giving them the necessary skills to be successful in the working world. Each year brings a new intake of students with varying needs which are assessed on an individual basis.”

At Stellenbosch University, the Disability Unit forms part of the Centre for Student Counselling and Development, which offers a range of services such as counselling for personal challenges, and academic support workshops in time management, stress management, and study skills.

The Disability Unit has been in place since 2007. With inclusive education in South Africa, and more and more students furthering their studies post matric, the need for disability support services has grown.

Students need to be underperforming in order to access academic assistance. Ultimately, the unit aims to create an enabling environment that empowers students with disabilities to achieve their full potential by creating awareness and enabling effective integration into campus life and the student community.