Tributes

Farewell to a mensch of the struggle

Norman Levy, a mensch of South Africa’s struggle for liberation, has died. He was 91. Norman and his identical twin brother, Leon, began their political activity as school boys and campaigned for freedom and equality all their lives.

The brothers stood in the dock with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Joe Slovo, Helen Joseph, and 150 other leaders of the liberation movement in South Africa’s “trial of the century” – the 1956 Treason Trial.

In an interview with the Levy brothers in 2020, I asked them if they were the last living Treason Trial defendants.

“Could be,” Norman said, and the twins rattled off names of fellow activists who were on trial with them. All the people they named had died.

“I’m not sure about the last, but I think it’s safe to say that we are one of the few left,” said Leon.

“I think you mean we are two of the few left,” corrected Norman.

The brothers were born on 7 August 1929 in Johannesburg. Their parents, Mary and Marc Levy, were immigrants from Lithuania.

The boys had just turned six when their father died. It was a difficult time for their mother, who had four children to look after, and the twins spent a lot of time on their own.

The brothers had similar ideologies but took different paths to becoming radicals. Leon joined the socialist-Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, but Norman rode headfirst into leftist politics when he was 14.

He had gone on a bicycle ride around the streets of Hillbrow and turned a corner into a gathering that was being addressed by Hilda Watts, the Communist Party candidate for the Johannesburg Municipal Council. He was enthralled by what he heard, and the next week, joined the Young Communist League.

When he was 17, Norman joined the Communist Party of South Africa, and the South African Congress of Democrats.

Norman, who became a teacher, was involved in the Defiance Campaign of the early 1950s to protest against unjust laws, and later campaigned against the National Party’s evil Bantu Education system.

He was also involved in the area committee of the Communist Party, which was operating underground. A month after Mandela and company were sentenced in the Rivonia Trial, the state cracked down on anti-apartheid activists.

Norman was arrested on 3 July 1964, and placed in solitary confinement where he endured endless interrogation sessions at the hands of the notorious Special Branch. The state eventually charged him and 13 other activists, including the lead counsel in the Rivonia Trial, Bram Fischer, under the Suppression of Communism Act.

Norman, who was married with two small children, was found guilty and handed a three-year prison term.

He knew what the risks of being involved in the struggle entailed, and resigned himself to serving his sentence at Pretoria Central.

He could write only one letter every six months, he had no newspapers or magazines, and was allowed very few visits, but he used his time to study for an honours degree in history.

When Norman was released in 1968, he arrived home from prison to find his five-year-old son, Simon, upset. Simon had found a dead bird which he held in his hand.

Norman looked at the bird and saw that the family was frozen, realising it would take them time to thaw.

Although he was free, Norman was prevented from working in his profession and restricted in his movements, so two months after his release, Norman and his family went to England. Leon, who had been detained under the 90-day detention laws, and his wife, Lorna, had already left the country.

In exile, Norman worked for a gentleman’s clothing shop and then won a fellowship to complete a PhD at the London School of Economics. He became a professor at Middlesex University.

Norman returned to South Africa after the African National Congress was unbanned, and helped design affirmative-action frameworks for the labour relations forum of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa. Mandela appointed him to the Presidential Review Commission, which looked at reforming the public service.

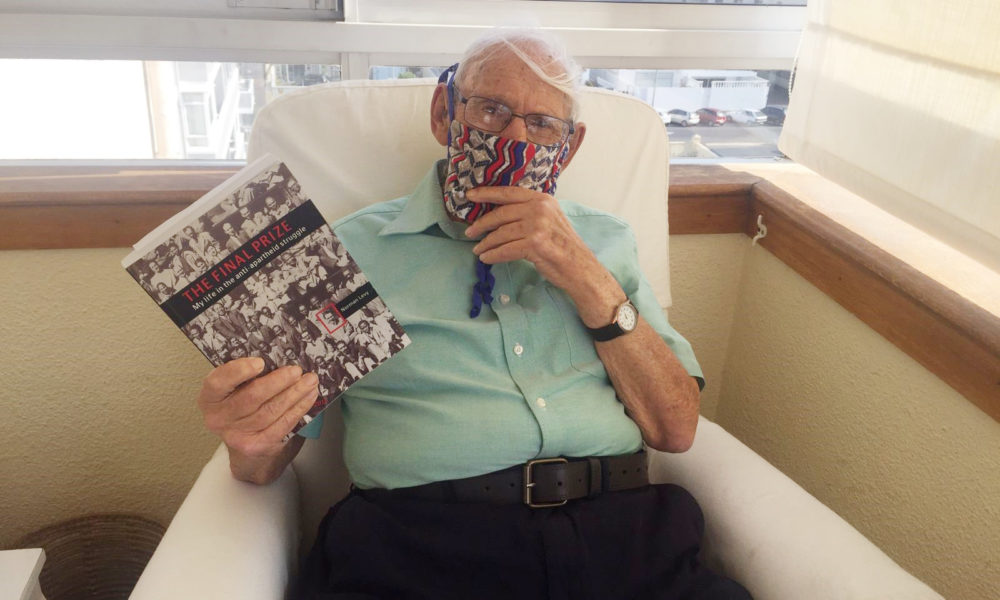

He eventually retired in 2011, and wrote his memoir, The Final Prize, in which he reflected on his involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle.

Patric Tariq Mellet, an activist who was in a communist cell with Norman in the 1980s, described him as “a great comrade, friend, and mentor … and a real gentleman”.

“It’s very sad as one by one, this generation of amazing human beings passes on,” he said.

Norman was diagnosed with lung cancer eight weeks ago, and died peacefully at his Cape Town home surrounded by his family.

Principled, humble, good-humoured, and selfless, Norman remained steadfast in his commitment to building a just South Africa. In spite of his enormous contribution to the fight against apartheid, he never considered himself a “struggle icon”.

Norman is survived by his children, Deborah, Simon, and Jessica, and his identical twin brother, Leon, the last living member of the 1956 Treason Trial.