News

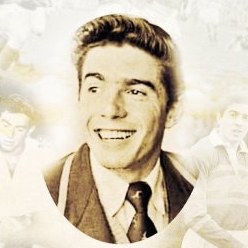

Farewell to ‘the flying dentist’

MOIRA SCHNEIDER

Rosenberg, dubbed “the flying dentist” due to his trademark dive when scoring a try, passed away in Israel on 14 January after a sudden stroke. He made aliyah in 2009 to join his daughter, Nicola Krost, and family, and had been living at Beth Protea, Herzliya.

Rosenberg played rugby for Jeppe High School, then the University of the Witwatersrand while studying medicine, then Transvaal, before becoming a junior Springbok.

Between 1955 and 1958, he played for the Springboks and became a sporting legend in both rugby union and rugby league. He played professional rugby league after relocating to Leeds University to study dentistry, when he changed his position from centre to wing.

While there, he set a club record (that still stands) of scoring the most tries in a season – 48 during 1960/1 – helping his club win its first championship title.

Rosenberg retired from the game and returned to South Africa in 1964 with his wife, Elinor, and baby Nicola, establishing a dental practice on the West Rand. Two more children, Andrea and Adam – who was later to play rugby for Transvaal schools and the under-20 side – were born in this country.

However, tragedy struck in 1970 when a stroke ended Rosenberg’s dental career. Not one to let a setback define him, he turned to boxing promotion and rugby journalism.

The grit and determination that had served him well on the rugby field resulted in him rehabilitating himself. Defying doctors who said he would never walk again, Rosenberg went on to run 10 Comrades Marathons and played first league squash.

He was the third South African to be inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1994.

In spite of his myriad sporting accolades, his “real joy” was his family, says Krost. “He was always very proud of his children and grandchildren.”

Rosenberg’s father, Philip, was an Orthodox rabbi who obtained his ordination at Jews’ College, London, the pre-eminent rabbinical seminary at the time.

In addition to serving as the first rabbi of the Green and Sea Point Hebrew Congregation, Rabbi Rosenberg held positions in Jeppe, Kensington, Bertrams, Middelburg, Witbank, and Windhoek.

In the 1950s, Rabbi Rosenberg travelled to the United States and was impressed with the Reform movement as a “very good alternative”. In fact, he practised as a Reform rabbi in Port Elizabeth from 1958 to 1961, returning to the Orthodox rabbinate in the early 1970s, according to Rosenberg’s sister, Vivienne Kramer.

When asked how as a rabbi he could allow his son to play rugby on Shabbat, Rabbi Rosenberg’s famous reply was, “My son was born with a G-d given talent. Who am I to argue with G-d?”

Rosenberg was one of the so-called “rugby minyan”, the 10 Jewish Springbok rugby players, a painting of whom hangs above the fireplace in Krost’s home.

“My brother said that what really kept him going during the games was the roar of the crowd,” Kramer remembers him saying of his rugby playing days. “He loved to hear it – it gave him a big rush.

“My parents saw him play only once each,” she recalls. “My father kept Shabbat, and my mother was too panic-stricken to watch him.

“I went with my mom on one occasion when we were in Leeds, and she nearly had a heart attack every time anybody even touched him! She was like, ‘Oh my goodness, Wilfred! Wilfred!’ She was beside herself,” recalls Kramer.

“One thing that stood out for me was how humble he was in terms of what a legend he was. I was once walking with him and some stranger came up to him and said, ‘Wilf, how are you?’ and shook his hand.

“My brother chatted to him, laughed and talked. Afterwards, I said, ‘Who’s that?’ He said: ‘I don’t know. People do this to me all the time.’

“Whoever approached him, he would be friendly, he would stop, and give autographs.” She remembers an incident from 1960 when she and Rosenberg were visiting a small town in the Eastern Cape.

Word had somehow got out that Rosenberg was in town. “When we went outside, the street was filled with people standing silently, clutching their autograph books and rugby balls.

“He just moved among them, saying hello, signing autographs, making small talk. It was really very lovely to see.”

Krost agrees. “He was such a great sporting personality, and a hero to so many, but to us he was really just our father,” she says.

“He was an amazing father who, together with my mother, instilled amazing values in his three children. We always knew he was a great sporting personality, but only on his death are we coming to realise how popular and what a legend he was all over the world.”

She speaks of the “positive aura” Rosenberg exuded as a striking feature. “There was never, ever a negative word that came out of his mouth. He was such a happy individual.

“Whenever my children and I asked how he was, he would always say, ‘I’m living in Israel with my children in the most amazing place. What more could I want from life?’”

For daughter Andrea Jayes, it was “very hard” to come to terms with Rosenberg’s sudden death, as he was “a larger than life character. He was always humorous, full of life, friendly to everybody, treated everybody with respect, and was just so humble and so happy with his lot, his life, and his children.”

The “most devastating” thing that happened to Rosenberg was the loss of his wife, Elinor, who died at the age of 51 years in 1989, Jayes says. “He never recovered from that.

“For us children, a large part of him went with our mother. When he took his last breath, my brother-in-law, Alan [Krost], said to him, ‘You can now rest peacefully with your Elinor Jane.’”

Rosenberg never experienced anti-Semitism during his rugby career. “Actually the opposite”, says Nicola. His Springbok coach, Dr Danie Craven, says Alan, “was very happy that he had a ‘Jood’ in the team, something he regarded as good luck”.

Sam Rubin

January 24, 2019 at 12:30 pm

‘A great pity that very little coverage of the passing on of Wilf appears in any English Newspaper in SA.’