World

Fighting Jewish stereotypes in China TikTok for this rabbi

JTA – With two degrees in Asian studies and 15 years of his life spent living and working in China – everything “from acting to the diamond business to real estate” – Rabbi Matt Trusch has a lot of experience with China.

But antisemitism wasn’t one of those experiences until he began posting on Douyin, China’s TikTok, from his home back in Texas in 2021.

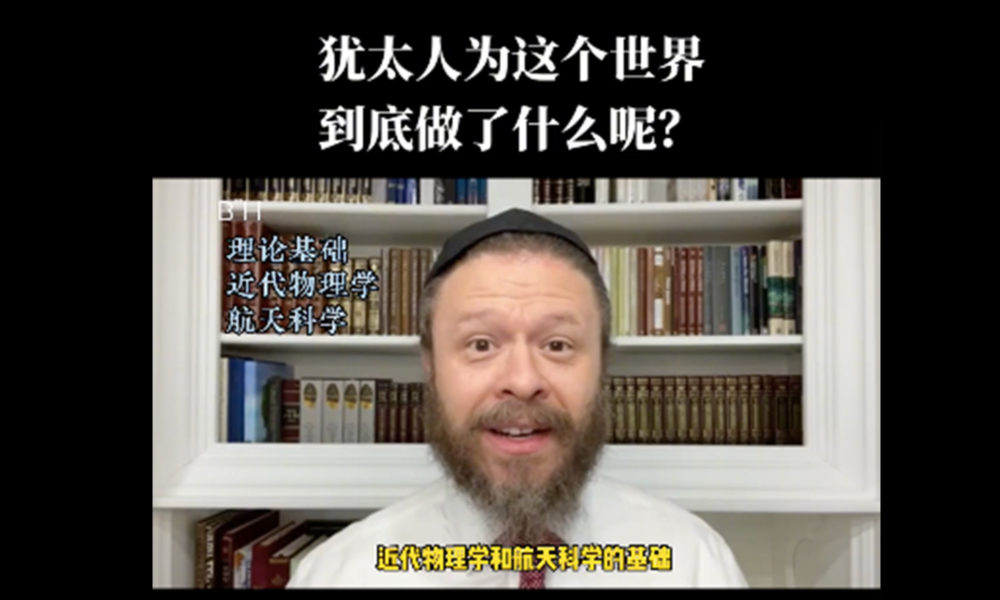

Speaking in fluent Mandarin peppered with Chinese idioms and filmed in front of a bookshelf lined with Jewish texts, Trusch passionately shares Jewish parables from the Talmud and the Tanya – a book of Hasidic commentary by the rabbi who founded the Chabad Orthodox movement – and the life and business lessons they may offer Chinese viewers. With nearly 180 000 followers, his videos have accumulated nearly 700 000 likes.

But the comment section under Trusch’s videos is revealing. In China, the line between loving Jews and hating them for the same stereotypical traits can be thin. On his most viral video, which has more than seven million views and explains how China helped give refuge to Jews escaping Europe during World War II, comments laced with antisemitic tropes seem to outnumber the ones thanking Trusch for sharing Jewish culture and wisdom.

“You don’t want to take my money, do you?” reads one top comment. “Wall Street elites are all Jews,” another comment says; others call Jews “oily people”, a play on the Chinese characters that spell out the word for “Jew”. Many blame Jews for the mid-19th century Opium Wars between China and foreign powers, or for inflation in pre-World War II Germany. Other commenters repeatedly ask Trusch to address Palestine on videos that have nothing to do with Israel.

The comments reflect the fact that in the minds of many in China, the Talmud isn’t a Jewish religious text but a guide to getting rich. The belief has spawned an entire industry of self-help books and private schools that claim to reveal the so-called money-making secrets of the Jews.

In his Douyin bio, Trusch appeals to this belief, describing himself as a rabbi who shares “wisdom of the Talmud”, “interesting facts about the Jewish people”, “business thought”, and “money-making tips”. Trusch told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that appealing to Chinese stereotypes about Jews was a strategic decision meant to expose more Chinese people to Jewish precepts.

Appealing to Chinese interest in the Talmud as a business guide is strategic for another reason: religious activity is complicated in China, where Judaism isn’t one of the five recognised religions, and proselytising by foreigners is forbidden.

“Pirkei Avot and the Talmud don’t mean religion in China, even though those are Jewish texts that we learn Torah from,” Trusch said. “If I were to say, ‘I’m going to teach Torah concepts in China’, that would probably be forbidden. But if I talk about things from the Talmud, then it’s not threatening.”

Trusch always had an interest in China. After getting an undergraduate degree in Asian studies at Dartmouth College and a master’s degree at Harvard University, he spent 12 years in Shanghai doing business in a range of industries. While he was there, he grew closer to Judaism and began flying to Israel every two weeks to study at a yeshiva there.

In 2009, Trusch moved back to the United States with his family and settled in Houston, where he’s active at two Chabad centres. Still, he made frequent visits to China on business (including starting his own Chinese “white liquor” company called ByeJoe) until the pandemic struck in 2020. With no way to visit China in person, Trusch and his partner began making videos about Judaism on Douyin as a way to connect with people there.

“When I was in China, I very rarely felt anything but a fond appreciation of Jews” from Chinese people, Trusch said. He was aware of the stereotypical way Chinese people think about Jews: as intelligent and business-savvy, paragons of worldwide wealth and power, with control over Wall Street and the media. Much of the time, these traits are viewed with admiration.

And yet, some of the most popular antisemitic comments on Trusch’s videos reference the so-called “Fugu Plan”, a 1930s proposal by several Japanese officials to settle 50 000 German Jews in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. Some in the Japanese leadership were inspired by the antisemitic forgery Protocols of the Elders of Zion, believing that resettling Jews in occupied China would attract great wealth and the favour of world powers like Britain and America.

The Fugu Plan never came to fruition, but the antisemitic and ultranationalist political blogger, Yu Li, (who blogs under the name Sima Nan) has shared the story with his nearly three million followers. In a 20-minute-long antisemitic rant, he said the Fugu Plan was evidence that the Jews colluded with the Japanese to establish a Jewish homeland on Chinese territory – a conspiracy that fits a nationalist narrative that China is constantly under attack by foreign powers.

Sima Nan isn’t the only prominent figure known for antisemitism. Even in a country with as few as 2 500 Jews – mostly foreign nationals – among 1.4 billion Chinese, antisemitic conspiracy theories appear to be alive and well, at least among online commenters, anti-Israel leftists, and some prominent Chinese nationalists.

Jews living in China are likely to tell you that they’ve rarely experienced what they would consider antisemitism. As in any other country, young people on social media are being introduced to antisemitic ideas and conspiracy theories – such as a correlation between Jews and COVID-19 – that they would be unlikely to encounter elsewhere, said Simon K Li, the executive director of Hong Kong’s Holocaust and Tolerance Centre.

One recent study of China’s online “alt-right” community didn’t find signs of significant antisemitism, but Kecheng Fang, a co-author of the study, said it’s no surprise that “sensationalist nationalist” figures are spewing antisemitism online.

Chinese authorities are aware of hate speech online. In June, a BBC investigation into an industry of racist videos popular in China prompted a response from the Chinese government. China’s embassy in Malawi, where one racist video was shot, said it “strongly condemn[s] racism in any form, by anyone or happening anywhere”.

Later that month, China released a set of draft rules instructing content platforms to review social-media comments before they are published and to report “illegal and bad information” to authorities. But these developments haven’t seemed to have made much impact, at least on Trusch’s videos, which receive a fresh set of antisemitic comments each time he posts daily.