OpEds

Freedom: the pangs of birth

I’m told that the moment of birth is painful, bloody, and messy. So, too, was the birth of our democracy in South Africa. More than 300 years of colonial and minority rule, violence, resistance, bloodshed, and oppression ended on a single day, on 27 April 1994, 28 years ago this week.

On that day, South Africans stood in endless meandering lines, maids and madams, bosses and workers, the impoverished and rich, Jew, Christian, Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, Buddhist and Jain, all standing together in queues to decide the fate of our nation.

Not through the barrel of a gun, but miraculously, through the slot of a ballot box, the Rainbow Nation was born.

The date of 27 April 1994 to hold the country’s first democratic elections was set in stone by the multiparty Transitional Executive Council that governed the transition. The date was an unmovable milestone on the road to democracy and liberation. But those who set the date had little inkling of what it would take to pull off the largest logistical operation in South African history.

In December 1993, on a crackly almost inaudible conference-call line, FW de Klerk and Nelson Mandela phoned Judge Johann Kriegler in Plettenberg Bay to tell him that he had been appointed chairperson of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), the independent government-funded body that would run South Africa’s first and subsequent elections.

The line was so poor, Kriegler misheard the two presidents and didn’t realise that he had been appointed chairperson – the one with whom the buck stopped – until he returned to Pretoria at the end of his summer vacation.

How does one put together an election in less than four months, with no voters’ roll, no understanding of how many people are eligible to vote, or even where they live? No census of black people had been done in decades, and no maps existed of townships, rural areas, and squatter camps. We were, in essence, meandering in the dark.

With the help of South African Breweries (SAB now SAB Miller), beer-distribution was used to try predict where populations resided. But this methodology was far from foolproof as SAB didn’t deliver beer to shebeens in many of the townships. In the Johannesburg City Hall where the late Dennis Fox ministered as presiding officer, six concurrent streams of voting remained almost unused as no-one lived in that area in spite of significant alcohol sales in that vicinity.

In areas such as Daveyton and Katlehong, queues stretched more than 16km as we battled to ship enough ballot papers and voting equipment to accommodate hundreds of thousands of voters we just didn’t know were there. The presiding officer in one such location told me the story of a 93-year-old lady who stood in the sun all day, waiting for ballot papers to arrive. He begged her to go home, promising that he would call her the moment additional ballot papers arrived. She replied, “I’ve waited 93 years for this, I can wait a little longer.”

Voting papers were running short, and Kriegler gave the instruction to print tens of millions of ballots overnight. The bottles of indelible ink used to mark a voter’s thumb were used up well before the election ended, and Dr Wouter Basson, better known as “Dr Death”, the head of the country’s chemical and biological-warfare programme, brewed a new batch of the indelible ink overnight, helping to save the election.

Advocate Anthony Stein, then a law student working for me, got covered in indelible ink when a palette broke while loading a Casper police vehicle to deliver additional ink to one of the struggling communities. Stein was covered head to toe in ink, visible, however, only under ultraviolet light. As he hadn’t yet voted, I escorted him to the polling station myself to convince the presiding officer who refused him a vote, as he was already marked with indelible ink, that no-one who voted was marked with indelible ink on their legs, arms, head, and shoulders.

Five hundred thousand election staff recruited, trained, and deployed by Maxine Hart delivered the election in 25 000 locations around the country. Selma Browde, who was Johannesburg electoral officer, used her grandchildren to mark the Nasrec showgrounds with signs to bring ballot boxes for counting because no staff were available, and because no-one had told her that she was responsible for the counting as well.

The election came at a time of chaos and violence. The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement), led by Eugene Terre’Blanche, conspired with the leaders of the “independent” Bantustan homelands, to scupper the elections. Right-wing elements set off bombs at the African National Congress (ANC) officers in Johannesburg and detonated explosives at Jan Smuts Airport (now OR Tambo International Airport). Helen Suzman spent a long while screaming at me because she was forced to hide in a police vehicle while visiting what was generally referred to as an election “no go area”. The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) had turned many of the townships and hostels into war zones as it attempted to protect its privileged position and the status of the Zulu king prior to any election. The IFP march on Johannesburg with at least 20 000 Impis armed with assegais and knobkerries resulted in the Shell House massacre which alone left 19 people dead in its wake. That morning, when I arrived at my office, dead bodies littered the pavement outside our building.

Ultimately, Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the IFP were brought into the election with the help of Colin Coleman and Kenyan diplomat Washington Okumu, after Henry Kissinger had left in despair. As part of the deal, De Klerk quietly signed the Ingonyama Trust Act into law, giving the Zulu king much of rural KwaZulu-Natal as a fiefdom.

With the IFP now entering into the elections and the ballot papers already printed overseas and flown in, tens of millions of IFP stickers were printed and affixed to the bottom of each ballot paper.

The election results were magically balanced. The ANC failed to achieve a two-thirds majority, the National Party secured enough votes to justify De Klerk a deputy presidency, and the IFP would have Prince Buthelezi in cabinet as minister of home affairs. It was, in fact, a national unity government.

On 9 May 1994, I lay on the lawns of the Union Building in Pretoria and amongst the throng of hundreds of thousands of people, I fell asleep. I had not slept in weeks.

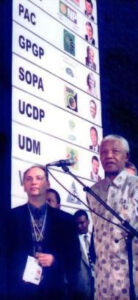

Blessed by Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris, Mandela took the oath of office on the stairs of the Union Building, as the first democratically elected president of South Africa.

And so, 27 April became the birthday of our nation. Every five years we return to the ballot box and are given the opportunity to overthrow our government, in an ordered and peaceful manner, should we choose to do so.

No matter what I do in life, the sheer exhilaration of helping to deliver peace, freedom, and democracy to the people of South Africa will always be my proudest moment.

- Howard Sackstein is former executive director of the IEC, and is chairperson of the SA Jewish Report.