OpEds

From exodus to endurance: a story still being written

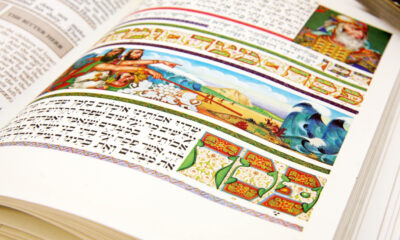

Passover has always been a story of defiance and deliverance. A saga of struggle, confrontation, bravery, identity, and ultimately freedom. It’s a story of a people who, through fire and flood, slavery and salvation, found not just escape but meaning. Who understood that survival isn’t merely about getting through, it’s about what you build in the aftermath.

This year, as we sit around our seder tables, we find ourselves not just recalling history but staring directly into its repetition. Once again, we’re pleading, not “Let my people go!” but “Let our hostages go!” Once again, we find ourselves cast as the eternal antagonist in a world that should know better. And once again, we wrestle with what it means to be Jewish in a time of darkness.

But Judaism has never been a faith of despair. We don’t dwell just in lamentation; we live in transformation. Every symbol on our seder plate is an act of defiant optimism. The salt water of our tears becomes the vessel in which we dip our greens, representing renewal.

The mortar of our oppression, our forced labour under Pharaoh, is repurposed into charoset – sweet, rich, spiced with cinnamon and wine, a reminder that we will take what has broken us and turn it into something that sustains us.

And then, of course, there’s matzah. The bread of affliction. The simplest of foods, born out of urgency, yet celebrated as the centrepiece of our Passover meal. A stark reminder that freedom rarely comes in comfort. It comes in haste. It comes in hardship. It comes when there’s no time to let the bread rise. And still, we make it a feast.

This is the Jewish way. We don’t just survive. We build.

Echoes of then and now

But this year, as we ask, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” perhaps the more pressing question is, “Why is this time no different from all other times?”

Because we’ve been here before.

The attacks against our people – whether in ancient Egypt, medieval Europe, pogrom-ridden Russia, Nazi Germany, or on the streets or university campuses of today’s world – aren’t new. The accusations may change slightly, the logos on the banners may differ, the excuses evolve, but the underlying hatred remains constant.

And yet, so does something else.

The unwelcome resilience of the Jewish spirit.

We’re here because we endured. Because when the world cast us out, we created. When our temples were destroyed, we built synagogues. When we were expelled, we carried our traditions in our suitcases, only to lay down new roots wherever we landed. We took the world’s attempts to erase us and turned them into stories of renewal, of learning, of triumph.

But it’s not just endurance that defines us. It’s vision. It’s action. The exodus wasn’t just a tale of miraculous escape; it was the foundation of a people who, in the depths of the barren wilderness, received the ten commandments, a moral code as powerful today as it was then. It wasn’t just about leaving Egypt; it was about what came next. About who we would become.

And today, in an era when the Jewish people once again find themselves besieged, maligned, and fighting for the simple right to exist in peace, this question remains: who will we become?

The afikomen and the inner search

When I was a child, one of the highlights of our seder was the great afikomen hunt. I hardly ever found it first, but that never stopped me from trying. The real joy wasn’t just in winning, it was in the search itself. The excitement of discovery. The possibility that it could be hidden anywhere. The thrill of looking under cushions, behind bookshelves, inside the folds of a napkin.

This year, as the children at our tables dash around in pursuit of the afikomen, pause for a moment and ask yourself: what’s the afikomen I need to find?

Not the one wrapped in a napkin, but the one buried within myself.

What part of me have I lost in the chaos of today’s world? What do I need to rediscover, not just for survival, but for growth, for acceptance, for gratitude, for joy?

Maybe it’s hope; maybe it’s faith; maybe it’s a sense of belonging; maybe it’s the simple ability to laugh freely again.

The afikomen isn’t just a game. It’s a metaphor. For what has been hidden. For what must be found. For what we as a people must reclaim, not just from others, but from within ourselves.

The burden and blessing of being Jewish

There’s a weight to being Jewish. A double-edged sword that comes with being part of a people who have survived empires, crusades, genocides, and exiles, only to thrive time and time again. Our existence is both a blessing and a burden.

The burden is that we must constantly defend ourselves, explain ourselves, justify our right to security, to nationhood, to life. We’re asked to hold ourselves to moral standards no other people are required to meet, while those who demonise us refuse to hold themselves to any.

The blessing, however, is far greater.

It’s that we’ve endured. That we have taken the pain of every era and turned it into wisdom. That we continue to teach our children not just how to fight, but how to heal. And how to live and love.

That in a world that so often chooses destruction, we choose creation. That in times of darkness, we light candles. That we are a people of doctors, engineers, artists, and thinkers. A people who take broken tools and broken times and build.

That’s why, in spite of everything, we don’t give up.

Hope is a Jewish imperative

The Torah tells us that when the Israelites were trapped between Pharaoh’s advancing army and the sea, Moses lifted his staff, and the waters didn’t part immediately. Instead, it was Nachshon ben Aminadav, a prince from the tribe of Judah, who stepped forward first, walking into the waves, deeper and deeper, until the sea reached his mouth. Only then did the waters split.

This is what it means to be Jewish. To walk into the unknown. To step forward in faith. To understand that miracles come, but first, we must act.

So this year, at our seders, we don’t sit in despair. We sit in defiance, in remembrance, in faith, and in action.

We will not stop fighting for our hostages.

We will not stop standing up for Israel, for Jewish life, for our right to be a people free from persecution.

We will not be silent when we see injustice – not just against Jews, but against anyone suffering under oppression, because we know that pain.

And we will not give in to hatred. Because that isn’t our way. Because our legacy isn’t destruction, it’s creation.

So, as we dip our bitter herbs and ask our four questions, let us ask a fifth:

What will we do with this moment?

The answer, as always, is to build; to educate; to protect; to create; to continue.

Because this is our exodus, but it’s also our becoming.

A final thought

The afikomen is always hidden, but never lost.

Neither are we.

This Passover, may we find what we’re searching for.

And may we, as always, emerge stronger, wiser, and ready to build again.

Chag Pesach sameach. Am Yisrael Chai.

- Mike Abel is the founding partner and executive chairman of M&C Saatchi Abel and The Up&Up Group, South Africa.