News

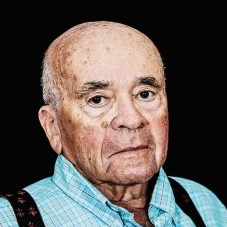

From Gulag to Gauteng: Celebrating the life of Stalin survivor

JORDAN MOSHE

These words, uttered by the late Mordechai “Mord” Perlov from his bed in intensive care at the end of last year, shows much more than inimitable perspective about what would ultimately lead to his passing. It captures the tenacity of a 93-year-old marvel who not only endured the unspeakable, but whose wit and warmth transcended circumstances until the last.

A survivor of Stalin’s brutal oppression, Perlov passed away on Monday after spending three weeks in hospital in December. His admission was the result of eating a spoiled cheese blintze, causing subsequent food poisoning, kidney failure, and death. He died at home in Melrose Arch this week.

His passing brings to a close a saga of note. Born in 1926 in the shtetl of Rasein in Lithuania, Perlov and his family were part of a community of about 5 000 Jewish residents. His family owned a timber and flour mill, and lacked nothing. All this would change when Stalin occupied Lithuania in 1939. In June 1941, one week before Hitler attacked Russia, about 20 000 so-called “enemies of the state”, were deported and sent to remote locations, facing harsh labour and unspeakably dire living conditions. Perlov, his brother Yaakov, sister Tova, and his parents were among them.

In spite of losing his parents (burying them with his own bare hands), Perlov would survive the ordeal against all odds, and escape Soviet territory. His journey took him through northern Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Italy, Cyprus, Israel (where he fought in the War of Independence), and eventually to South Africa, where he became a successful businessman, married, and had three children.

Along the way, Perlov touched countless lives, and although he opened up about his ordeal only a few years ago, people knew he was remarkable after first meeting him.

“This was a man who suffered terrible persecution but refused to be a victim,” says financial specialist Michael Kransdorff. “He escaped from a Soviet gulag, got a university degree in spite of not having a formal education, built a successful business, and raised a family. He was my hero, and my friend.”

To those who didn’t know him, Perlov seemed a taciturn man of few words. “When you got to him, he opened up,” says businessman Rob Katz, whose connection with Perlov went back more than 30 years when he befriended Perlov’s son, Roni, at university. “I knew so little of his background that I thought he was Russian.

“When I realised he was Lithuanian and had survived the Gulag, it didn’t really change anything. He was still Mord, but there was more to him.”

Marketing communications specialist Michelle Blumenau recounts a similar experience. “There was this old guy who always sat in the front row at Chabad of Melrose who never spoke,” she says. “I’d heard he’d had an interesting life, but I never engaged with him until his wife, Milly, died and I went to her funeral. We then struck up a friendship.

“Because his three children and grandchildren lived overseas, my parents and I ‘adopted’ him,” says Blumenau. “Every Monday night, he’d go out to dinner with my parents. He used to come to our Pesach Seder every year. The one year, my dad began the seder by saying that the story of the seder is one of slavery and freedom, and tonight we have amongst us someone who was a slave. Mord looked blank, and didn’t register that my dad was talking about him. He never saw himself as a victim.”

It’s perhaps for this reason that he began sharing his story publicly only in the past decade. When Blumenau suggested that he speak at a Limmud conference, she had no idea that he had never spoken publicly before.

“He gave a presentation to a packed room the following year with Kransdorff,” she recounts. “He got a standing ovation, and it unleashed something in him. He didn’t stop telling his story from then on. He wanted to expose the evils of Stalin and communism.

As soon as he opened up to people, Perlov became a relatable personality who could get along with virtually anyone. “Mord had an amazing ability to transcend intergenerational and cultural barriers,” says Kransdorff.

“Everyone loved him, from the waiters in every restaurant in the Melrose area where he ate almost every meal; to the school children he spoke to about his experience in the war and the horrors of soviet communism; to the numerous gym goers he befriended.”

Although they had met previously, Margaret Hoffmann, a close friend and confidante, developed a bond with Perlov after inviting him to participate in the Holocaust Survivor Group (HSG) at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre at which she volunteered.

“Mord had an amazing intellect, clarity of mind, and an ability to socialise and make friends with a diverse group,” she says. “Once at an HSG meeting with Achim L’Chaim, a group of injured Israeli soldiers, Mord shouted, ‘Anyone from my unit?’ Three soldiers pounced on Mord, hugging him and crying. He always joked about being given five bullets to fight in the War of Independence.”

Perlov’s sharpness of mind was paired with astonishing physical resilience until late in life. Blumenau recounts how Perlov joined her family annually to break the fast after Yom Kippur. “At the age of 91, I asked him how his day had been,” she says. “He told me that he had gone to gym at Melrose Arch, to shul, and had fasted all day. It’s hard to understand that level of resilience.”

Perlov was particularly proud of the publication of Once Were Slaves, an account of his harrowing journey written by his cousin, Rose Zwi, which he promoted often. He was even involved in producing a documentary about his life, Because of Stalin, which was recently released, and is due to be screened in cinemas later this year.

“He gave 250 signed book copies away at Tisha B’Av last year,” says Katz. “He never wanted payment for them, but asked instead that a donation be given to Hatzolah, an organisation close to his heart.

“That was the man. He always recognised what others had done for him. It was never about him, but about his message and helping others.”

Katz concludes that beyond suffering, Perlov’s life teaches us a lesson in endurance and living for what matters most. “Mord survived hell,” he says. “What he endured is not, however, the lesson here, but that he did endure and built a better reality. In him, we had a living testament of European Jewry of the 20th century, an embodiment of its highs and lows. Mord represented the triumph of spirit. He endured and built.”

Perlov is survived by his sister, Tova; his children, Ari, Roni, and Carmella; and his five grandchildren.