News

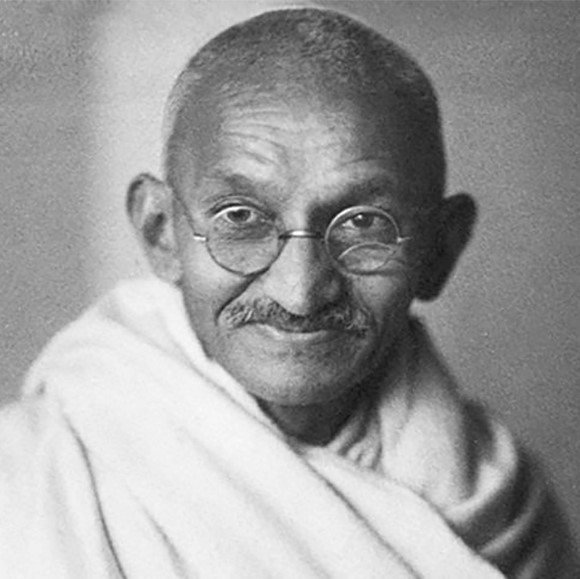

Gandhi’s formative years with SA Jews

MOIRA SCHNEIDER

So said Dr Shimon Lev, speaking about Gandhi and the Jews at the South African Jewish Museum in Cape Town on Sunday evening.

Lev was referring to Gandhi’s 21 “formative years” in this country – 1893 to 1914 – where the civil rights’ activist developed the non-violence (passive resistance) struggle. “Everything he did in India later, one can find the roots in South Africa,” he said, stressing that this period was “therefore very, very important”.

Gandhi, an Indian lawyer, was the leader of India’s non-violent independence movement against British rule, and advocated for the civil rights of Indians in South Africa.

Lev is an Israeli artist, curator, writer, and researcher. He holds a doctoral degree on the mutual influence of Jewish and Indian cultures, with a particular focus on Gandhi and his encounters with the Jewish and Zionist world.

Lev is in South Africa to conduct research on Gandhi for a new publication titled Gandhi and the Jews, The Jews and Gandhi.

He is the author of Soulmates, the story of Mahatma Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach, which is the first comprehensive study of the enigmatic relationship between the two men. Both were immigrants, Kallenbach hailed from Lithuania.

Lev drew attention to an interview Gandhi gave to the London Jewish Chronicle in 1931, during which he said, “I have a world of friends among the Jews. In South Africa I was surrounded by Jews.”

For many years, Gandhi had been “deleted” from the Jewish/Zionist discourse as he had written a “very problematic article” in 1938 which viewed Zionism as a colonialist project, Lev said. “Some even say Gandhi was anti-Semitic. “Of course, that’s not true. He was a universalist who later modified his objection to Zionism and the state of Israel.” When asked who was worse off, the Jews who were discriminated against or the Indian “untouchables”, Gandhi said the former.

On Gandhi’s attitude to the Holocaust, however, Lev said, “His sympathies were with the Jews, but he wasn’t in favour of a national home for the Jews.” When comparing the Jews in Germany with the Indians in South Africa, he had said the latter were worse off.

“This is completely wrong, and shows he didn’t understand what was going on,” said Lev, pointing out that it had resulted in his name being “deleted”.

In Lev’s view, “Gandhi probably modified his view on Israel after the Holocaust.”

Lev’s interest in the man was sparked many years ago when he undertook a trail across Israel and came upon the ashes of Kallenbach buried at Kibbutz Degania’s cemetery near the grave of AD Gordon, the spiritual force behind labour Zionism. Kallenbach was cremated by Reform Rabbi M C Weiler in Johannesburg. His ashes were interred for many years in a crypt on Linksfield Ridge in Johannesburg, before his relatives moved them to Israel.

Ironically in view of Kallenbach’s strong support of Gandhi, Indians were not allowed into the proceedings, and had to stand at the door, Lev said.

Amongst Gandhi’s other Jewish friends in South Africa, Lev mentioned Henry Polak (1882-1959), an English lawyer who Gandhi sent to India to lobby for the Indian cause in South Africa. He had been the first to publish a book about Gandhi and had “put his name out there”.

Kallenbach had been more the “intimate friend”, Lev stated, “but the stories about the relationship they had aren’t true”. Kallenbach was a successful architect who bought the piece of land outside Johannesburg on which Tolstoy Farm, Gandhi’s experiment in communal living, had been established.

The name of the settlement was in fact Kallenbach’s idea. Interestingly, it was established at the same time as Kibbutz Degania. One could view both as Tolstoyan settlements, noted Lev.

Sonja Schlesin became Gandhi’s secretary, having started working for him at the age of 16. Lev described her as “a feminist, ahead of her time”.

Louis Walter Ritch (1868-1952), another Jewish supporter, founded the Theosophical Society. In fact, most of Gandhi’s Jewish supporters came from Theosophical circles, Lev noted. “For many Indians, the fact that so many Western Europeans were interested in their wisdom, gave them confidence.”

Ritch had been sent to England by Gandhi to complete his legal studies and lobby for Indians in England, the colonial power. He later worked as a lawyer in Gandhi’s office.

Then there were the Vogls. “Mrs Vogl was very active in teaching sewing classes and organising the Indian Women’s Bazaar with Schlesin to help the family finances, selling Indian products when the men were arrested,” Lev said.

“Gandhi writes very positively about her.”

Gabriel Isaac was the only non-Indian to sacrifice his life for the Indian struggle. “He came out of jail (after the government’s ‘almost successful’ attempt to crush Indian resistance) totally broken physically and mentally.

“Almost nothing has been written about it which is very strange. There is complete silence about him. Even worse, Gandhi doesn’t even mention him in his autobiography,” Lev said.

“It’s a mystery. I’ve been trying to look for information about him.” Hailing from Leeds in the United Kingdom where his family had a big jewellery business, Isaac, also a jeweller, came here to escape family pressure, according to Lev.

He fought in the Boer War, then become a “very active” theosophist. It was, in fact, Isaac who introduced Polak to Gandhi at a vegetarian restaurant in Johannesburg.

Polak was the only one who wrote about Isaac after his death. When Polak, annoyed, questioned Gandhi about the omission, he had been “very apologetic”, saying that it had been “unintentional”.