Featured Item

Harber dissects the downfall of sensationalist journalism

“We need a return to journalism not as a commercial enterprise but as a sustainable public service. That’s what gives it importance and value in our society.”

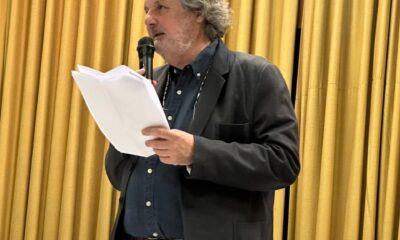

So said veteran journalist Anton Harber in an online interview hosted by the Jewish Literary Festival on Thursday, 12 November. Harber discussed his new book So, For the Record: Behind the Headlines in an Era of State Capture with journalist Sam Sole, the managing partner of the AmaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism.

The book brings the media into the spotlight, and aims to achieve something for journalists and consumers of news, Harber says.

“We need greater media understanding and literacy in this country,” he said. “People need to understand what journalists can and cannot do, the dilemmas they face, their importance as well as their limitations.

“That’s why I try to spell out how the process works, how news comes together, and the decisions made by journalists.”

People think that an editor sits and says, “put this in the paper” or “don’t put that in”, Harber says.

“It’s much more complicated and there are many subtleties. As journalists, we have to be aware of each of the decisions we make. We are taught to make them in an unconscious way, but I think there is a need to be absolutely conscious of the words one uses, the headlines, and the choices one makes.

“It’s not about the stories one does, but how one does each story. There is a great need for journalists and non-journalists to be much more aware of that process.”

Harber illustrated this by differentiating between “leak journalism” and investigative journalism, explaining how leaks have become a dominant force in the South African media.

“Investigative journalism isn’t the same as leak journalism,” he said. “Investigative journalism takes a leak, investigates the context, and verifies the story before using it as a foundation for a piece of journalism.

“In South Africa, because we have a dominant party which has splits within it, the leak has become a major tool of political battle, and journalists are critical to how that leak is received.”

The rise in social media has made this process far more complicated.

Said Harber, “Social media has changed the relationship between a source and a journalist. The source used to badly need a journalist as a gatekeeper who controlled access to the public. Because there are many more outlets and ways to get the information out without journalists, the source has become more powerful.

“That’s one thing that has tempted many journalists to deal with leaks at face value.” This, in spite of knowing that a source may have a nefarious agenda.

“In the Sunday Times story that the book unravels, one of the things that really surprised me was that they knew that the people who were feeding them information had agendas,” he said.

“Sources often do have their agenda and it doesn’t mean the information is necessarily not important, but the journalist’s job is to scrutinise the source and find others to back it up.

“Because of time and financial pressure on the Sunday Times, they were too quick to go with stories of dubious origin. Many people were offered many of the leaks. But why did the Sunday Times fall for it?”

Harber said he traced this phenomenon to a longstanding culture that had developed over many years.

“The Sunday Times was very powerful, wealthy, and a key agenda setter in South African news,” he said. “It developed an arrogance in that time, and a practice that worked. When you came with a story, it went through many editors who saw their jobs not as verifying but as sharpening the story.

“The Sunday Times’ treatment of a story was that it could have no more than 800 words, that it needed people at its centre, and a simple narrative. It took a position that said clearly if it thought people were guilty or not. It proudly called it the ‘Sunday Times’treatment’.”

With time, however, the newspaper began cutting corners.

Said Harber, “It would take out all the qualifiers in a story. It wanted one narrative, a fundamental distortion of journalism which is deeply misplaced.

“Great stories don’t have one narrative but complex, nuanced, conflicting ones. Our job is to provide conflicting narratives. It doesn’t mean we believe one over the other, but we tell readers that there is more than one at play.”

“The Sunday Times chose one, went with it, and would stick to it at all costs.”

Harber said that the rise of the internet undermined this culture, however, and the newspaper didn’t realise that it didn’t have the standing to hold this position when people could challenge it on social media within minutes of publication.

“The Sunday Times didn’t catch up until it was too late,” he said.

Consequently, it has become clear that the traditional newsrooms are under too much pressure.

Said Harber, “They’ve shrunk enormously in recent years, and their capacity, by and large, to do the kind of time consuming, complicated investigative work is much diminished.

“The good news is that what we’ve seen is the rise of independent, non-profit specialist units which often have less pressure of time and money and are producing some of the most important work across the world.

“The real surprise is that non-profit journalism is looking more sustainable than the traditional commercial model.”

Harber’s key message is that, “The Sunday Times mess ups are perfect examples of how when you go too fast, don’t verify properly, and just see yourself as being on a single track under pressure to produce front-page splashes, you’ll get it wrong.

“Accuracy, context, and detail are more important than speed. When journalists take a breath to verify the story, it’s more vital than speed. The speed of social media is causing enormous pressure, and I’m afraid that it’s putting us on very dangerous path.”