OpEds

I got to leave Poland

Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz wrote, “The living owe it to those who no longer can speak to tell their story for them.” At the time of writing, I have just returned from a week-long journey through Poland and Lithuania.

We travelled through cities and concentration camps, forests, and ghettos. We laughed, sang, cried, screamed, talked, and sat in silence. We expressed shock and anger, gratitude, and love. I’m almost grateful to be in quarantine on my return to Israel as it has given me the opportunity to rest, process, and reflect.

The first thing I noticed about Poland was the greenery. As our bus zoomed past field and countryside, my vision was a blur of green – trees, bushes, and tall grass. It was easy to be deceived by the foliage, and our tour guide was quick to remind us, “Every leaf, every blade of grass, and every patch of soil is splattered with Jewish blood.”

The death camps didn’t allow us to forget. Treblinka laid bare contrasted starkly with the materiality of Majdanek, but I struggled to conceptualise the reality of both.

Auschwitz, arguably the greatest symbol of the Holocaust, felt like a falsity. How was any of this real? How did the Nazis get away with massacring six million Jews in camps like these, camps that span acres of land, sometimes in plain sight, not even ashamedly hidden behind the tall trees of the Polish forests?

And yet, as I walked through these mass graveyards, I felt thousands of souls walking with me. I heard their cries and their pleas as we stood in a gas chamber singing, “Shema Yisrael”, and as we said the memorial prayer in front of the destroyed crematoria.

The forests’ tall, spiky trees bore witness to the millions that lay buried beneath their soil. Our feet trod lightly on soft earth, the blood of our people having brought life to the dense moss and underbrush.

Each city was filled with people giving us dirty looks as we sang our Chassidic niggunim loudly, standing outside old shuls that have been converted into a myriad of things – supermarkets, libraries, piles of rubble.

I was shocked as we walked through the old ghettos of Vilna and Krakow, the streets now filled with picturesque cafés and pumping bars, the only remnant of the atrocities that occurred there a few old street signs and some Yiddish writing on the walls. When I closed my eyes, I could almost imagine that the hundreds of voices were Jews and not tourists.

As our plane touched down in Israel, I felt an avalanche of emotions – exhaustion, relief, sadness, and gratitude – mostly gratitude.

I got to leave Poland. I got to come back to my beautiful homeland, and I have a future. I have life, and I intend to live it to the fullest, for my ancestors, for those Jewish souls that never got to leave.

Am Yisrael Chai!

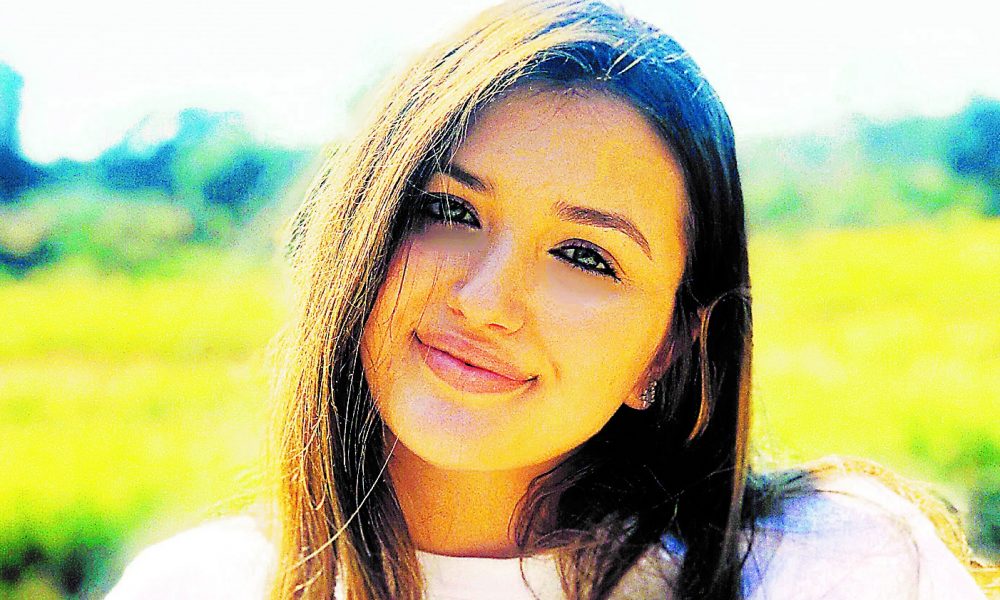

- Dani Sack is on Bnei Akiva’s MTA gap year programme, studying at Midreshet Harova seminary in Jerusalem.