Featured Item

Instead of the Promised Land, Jews landed on an island prison

MIRAH LANGER

The experience of these European Jews, who were deported to Mauritius, represents the closest the Holocaust ever came to the southern tip of Africa.

Vanessa Levaillant, a guide at the Jewish Detainees Memorial Museum and Information Centre in Mauritius, recently detailed the sorrows and strengths of this group when she spoke at the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre in Forest Town.

The refugees who landed up in Mauritius were, in fact, part of a larger group of 3 500 Jews from various parts of Europe who, in 1940, fled the Nazi regime to settle in Palestine.

Travelling on four ships, the refugees endured months of shocking conditions on their journey, including overcrowding and the spread of diseases like typhoid, dysentery and diarrhoea.

There were over 1 800 people travelling on one of the ships, the Atlantic, which had capacity for only 800 people. “It was so overcrowded… that the captain had to give orders to move to the left or right to stabilise the ship,” explained Levaillant.

At one point, the ship ran out of coal, so all the wood on the ship was burned except for one mast. “It was like a ghost ship. Just imagine: they need the ship to move, to carry on the trip, but actually they are destroying the ship.”

As such, when the refugees arrived at the Haifa harbour, their relief was palpable: “The passengers were rejoicing and singing Hatikvah.”

However, continued Levaillant, the refugees soon realised there was something suspicious afoot. Considered illegal immigrants in the British protectorate of Palestine, officials began loading the refugees onto their own ship, the Patria, in Haifa harbour. They planned to send the Jews to Mauritius, considered a safe harbour.

However, the Jewish paramilitary Haganah movement had different plans: “As they were transferring the passengers onto the Patria, there was a big blast. The Patria exploded.”

The Haganah had put explosives on board, intending only to delay the deportation so they could negotiate the right for the refugees to stay. They miscalculated the amount of explosives needed.

A total of 202 people, including British officers and refugees, died. The British kept the survivors for two weeks before sending these refugees to Mauritius.

The refugees tried many desperate ploys to avoid leaving, including stripping naked, thinking that as the British were considered gentlemen, they wouldn’t force naked people onto a ship, said Levaillant.

The 1 580 refugees, including 96 children, were nevertheless deported on December 12 1940 to Mauritius and were “transferred to [the prison in] Beau Bassin and incarcerated”.

“They were shocked,” Levaillant explained. “They had been through so many hardships, and they ended up behind prison walls.”

As families were separated into a men’s and women’s section, the refugees were also exposed to malaria. Dozens of people died in the first year on the island.

Nevertheless, there was also a great spirit of resilience.

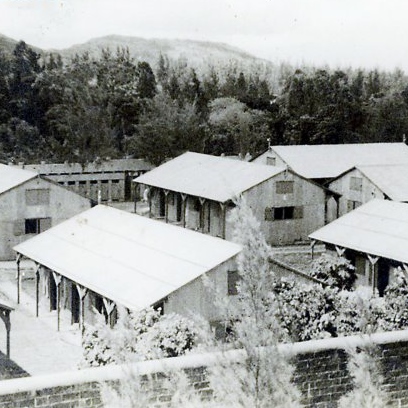

The detention camp housed two schools, two synagogues and bakeries. After some time, marriages were allowed and 60 children were born during the period of incarceration.

Said Levaillant: “The main reason the British detained all the people was a fear that there could be a Nazi spy among them.” Once it was clear that this was not the case, some teachers, doctors and musicians were allowed to work outside the camp.

In fact, a dancing band called Papa’s was established by refugee musicians and it became well known on the island.

Despite the fact that the detainees were from various parts of Europe, “they acted as one community”, explained Levaillant, noting that religious rituals such as Shabbat were observed.

She said the South African Jewish community assisted by liaising with the one Jew who lived in Mauritius at the time in order to send various supplies. Medication, prayer books and musical instruments were sent from South Africa to “ease their daily lives”.

Finally, on August 12 1945, the detainees were given the choice of returning to Europe or going to Palestine: “The majority chose Palestine,” says Levaillant. “Nothing was left after their departure.”

The camp buildings were flattened.“There was only one proof in Mauritius [of their existence]: the cemetery.”

The 128 graves of Jewish refugees who had died during their stay, including that of six children, remained.

In 2014, a memorial, housed in an old chapel in the cemetery garden to commemorate the Jewish detainees, was finally established.

This was the start of a life-changing journey for Levaillant, who had previously worked as a guide at a military museum.“Two days after the opening of the memorial, I witnessed the first tears… A lady came to visit. She saw her husband’s family name and started crying,” said Levaillant.

“I was not used to seeing people crying. I was used to the British Military Museum, of which I was very proud – but now I am seeing the other side of the… British colony.

“After this visit there was something different in me… After the tears, I could no longer assign numbers: there was a name on the graves and I wanted to find out more.”

Levaillant, who is not Jewish and describes herself as previously being “one of those who didn’t know anything about the Holocaust”, said she’d learnt a key lesson working at the memorial: that associating heritage with ethnicity is a “misconception”.“I have learned as a guide that heritage belongs to all of us. This is part of my country’s history and I want to contribute.”

Levaillant told of how her friend originally persuaded her to take the job by telling her that “the opening of this memorial will be just like a light that shines onto the Jewish cemetery – because it has remained in the dark part of Mauritian history”.“But,” added Levaillant’s friend, “this cemetery won’t be able to relate its story on its own. We have to give it a voice to make it alive.”

With her profound sensitivity, Levaillant has become that voice.