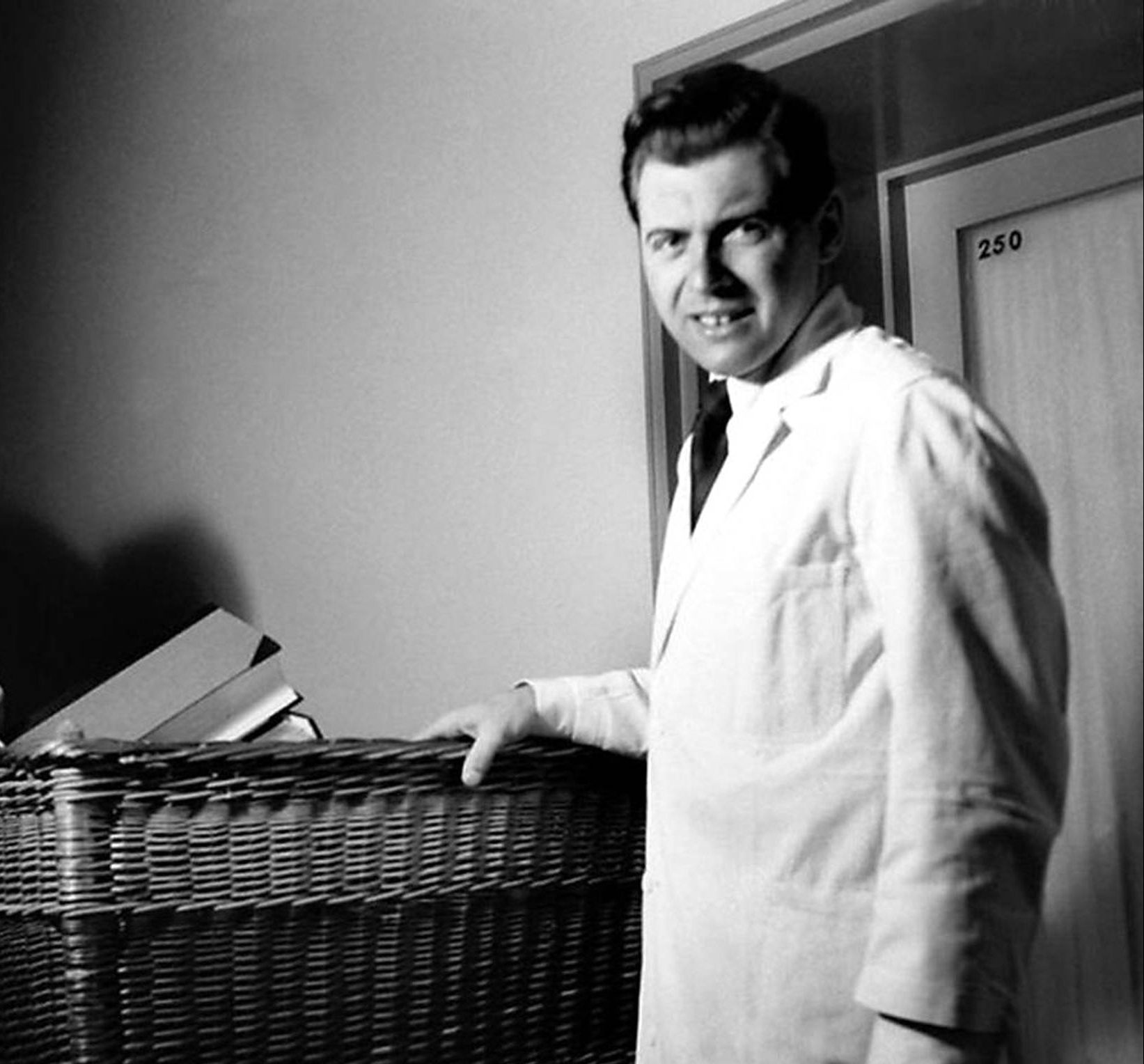

Featured Item

Investigating the Angel of Death’s twin persona

“If Auschwitz as a place stands as a symbol for the Holocaust, then Mengele as a perpetrator has come to serve a similar role for the death camp itself.”

So writes American historian and author David Marwell in Mengele: Unmasking the ‘Angel of Death’. If anyone embodies the evil of Auschwitz, it’s surely Dr Josef Mengele. From horrifying experiments to casual train-platform death selections, Mengele is remembered as the “Angel of Death” by surviving inmates of the camp.

Marwell discussed the infamous figure with Israeli historian, Tamir Hod, in a virtual lecture co-presented by Israel’s Ghetto Fighters’ House and the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre this past Sunday.

“If you look to his childhood for clues of the man he would become, you would be disappointed,” said Marwell. “There’s no evidence in his childhood home or activities as a child of him involved in killing cats in the yard or the like.”

He explained that Mengele grew up as part of a prosperous family in the town of Gunzburg, Bavaria. He was the first of three sons born into a home with wealth and parental support. A middling student, Mengele wasn’t terribly distinguished in his youth, but after enrolling at university in 1930, he began to display his first glimmers of interest in science that was to become his passion.

“He was the recipient of an elite education under Nobel prize winners, and became completely caught up with the science of genetics,” says Marwell. “He earned a PhD in medicine and anthropology, and together with genetics, these subjects became the basis for Nazi ideology.”

Mengele’s interest in these subjects led him to become involved in Nazism, though he didn’t join the party until 1938.

Marwell explained that the sciences he studied were elevated by the Nazi state. “The role of the physician was changed under the Nazi view,” he said. “They became responsible not for the care of the individual, but the racial well-being of a whole community. The individual was substituted with the collective.”

Mengele showed great promise in his field, and had the war not broken out, Marwell said he might have ended up as a lecturing professor at a university. However, the outbreak of hostilities changed his trajectory.

“He was assigned to the Viking division in 1941, then trained and deployed in Operation Barbarossa,” said Marwell. “He remained a combat physician for about 18 months until evacuated during the retreat from Stalingrad, when he was flown out in January 1943.

“In all, he served 18 months of uninterrupted, severe fighting and was exposed to mass shooting and intense combat, leading some to speculate that he suffered from some PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] later.”

Mengele was assigned to Auschwitz at the end of May 1943. “We don’t know whether he was sent or volunteered for it,” explained Marwell. “He really took to Auschwitz – it was something that unlocked him in some way.”

It was here that Mengele could pursue his scientific interests, carrying out research that benefitted not only himself but also his mentors at institutions in Germany. According to Marwell, many of the specimens Mengele took during the course of his work were sent to other researchers, advancing their research at the same time.

This included research into twins, a subject that enjoyed much popularity in scientific communities around the world at the time.

“Research on twins was a kind of standard protocol for genetic research around the world,” Marwell said. “When the war started, it became difficult because the supply of twins became limited. Those used in research tended to be young (as older twins tended to separate as adults), and young people had been sent away to the countryside. The supply of twins dried up.”

When Mengele arrived at Auschwitz, however, he had a nearly unlimited supply of twins coming off the trains, allowing him to engage in his own experiments and others on behalf of his colleagues in Berlin.

Marwell said Mengele also recruited assistants from among the deportees. “Imagine the number of physicians, anthropologists, and pharmacists that came out of rail cars,” he said. “There were tens of thousands. They weren’t willing, but Mengele forced them to conduct his research with him.”

The belief that Mengele experimented on twins in order to better the genes of “pure” Germans is difficult to prove, says Marwell.

“I don’t believe it’s true,” he said. “It ignores the long tradition of twin research so prevalent at the time, and it’s at odds with Mengele’s earlier research interests. It raises the question about what exactly Mengele’s research protocol was, and what he wanted to do at Auschwitz.”

Unfortunately, this can only be speculated about, as few records actually exist which can shed any light on what Mengele really aimed to achieve at the camp.

“There are some reports based on the testimony of people experimented upon, but sensitive though it may be, it’s difficult to rely on them to determine what Mengele’s objectives were,” he said.

“People who were subjected to experimentation can say what was done to them, but it’s difficult to know what Mengele was trying to do.”

For this reason, Marwell maintains that the picture of Mengele at the camp has become distorted. “There are countless testimonies of encounters with him that make it seem that his name became detached from the actual person, that somehow he has stood in for every German physician involved in selection,” he said.

“There were dozens of doctors on the platform, selecting in routine fashion on a schedule. Mengele wasn’t there all the time.”

Nevertheless, popular culture has come to fixate exclusively on the infamous doctor, partly as a result of the war-crime trials after the war.

“Mengele became a major figure in popular culture,” said Marwell. “There’s a whole series of Mengele-like caricatures which have populated culture since the 1960s. I couldn’t find the first use of ‘Angel of Death’, and I’m not sure when it happened, but he is certainly far more notorious and famous at that point than he was in 1945.”

Mengele’s infamy grew in the post-war period, and he came to stand for what had happened at Auschwitz and the evasion of justice by many Nazis.

“He has a twin persona that I think has distorted who he was,” said Marwell. “My book aims to replace the caricature with something far more unsettling – a human being.”