Religion

Israel a democracy, but seder shows we’re family

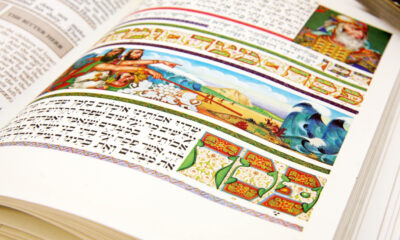

The seder isn’t merely a retelling of history, but a re-experiencing of yetziat Mitzrayim, a journey best undertaken through active dialogue. This question-and-answer format, generally characteristic of Talmud Torah, unfolds not in a Beit Midrash but around the seder table, woven into the fabric of family life. For thousands of years, across countless lands and cultures, we have transmitted our common story around the family seder table.

The very first seder marked the emergence of our identity not just as a nation, but as a family. On the night of yetziat Mitzrayim, we were commanded to offer the korban Pesach. The time frame for eating this korban is the most limited of any korban; it had to be consumed by midnight. Additionally, the meat couldn’t be removed beyond its original building. Hence, the most natural and logical arrangement for korban Pesach was for each household to bring its own korban offering, thereby assuring that the meat would remain at home and that it would be finished on time. As the Torah writes, “A lamb for each household, a lamb for each family.” Korban Pesach was an intimate, family-centred experience.

Centuries of slavery threatened to eradicate Jewish family life. Slaves, crammed into squalid quarters, rarely sustain stable family structures. They have little control over their children, who can be sold or bartered like mere possessions. Worse Pharaoh, who couldn’t bear the sight of a Jew, unleashed his fury upon our infants, decreeing that they be cast into the Nile. Tragically, history has repeated itself, and this gruesome crime continues to be inflicted upon our people.

That we still managed to preserve our families and gather for the seder, even under the crushing weight of slavery, was a testament to our resilient spirit and unbreakable faith.

Additionally, that first Pesach night, we coalesced into one family by realising that we shared a common father. We are all familiar with Moshe’s famous demand to Pharaoh: “Let my people go!” But this phrase, so often quoted, isn’t entirely accurate. The actual first message Hashem commanded Moshe to deliver was far more personal: “Let my firstborn child go, or I will take your firstborn.”

On the night of the first seder, as we gathered around our family korban and heard makkat bechorot (the plague of the firstborn) strike, we realised that Hashem wasn’t only our creator and redeemer, he was our father. If we all shared a common father who defended his children, then we weren’t merely a people, we were a family.

Family identity as the backbone of Jewish identity didn’t begin on the night of yetziat Mitzrayim. The entire story of Bereishit is the story of a family, one that wrestled with the classic struggles of family life: tensions between spouses and siblings; disputes over inheritance and legacy; the challenge of preserving unity; and the responsibility to protect one another. Our national history, long before slavery and redemption in Egypt, began not with a kingdom or a formal structure, but with a family taking shape.

Every year, the seder rebuilds our family identity. We gather with our families, ask our children questions, and pass down our story, reminding ourselves that the Jewish nation is, at its heart, a Jewish family.

We’ve always seen ourselves as a family, even when we lived far apart. When we lost the outward signs of nationhood – sovereignty, land, an army, a flag – we held fast to a shared family identity that bridged the continents that divided us.

Though we’ve lived as a family for centuries, something about life in Israel makes us feel even more like a family. We hear it often: one of the joys of living in Israel is the sense of being part of a family and treating one another as such. We feel more willing to step out of our comfort zones for each other, whether it means offering help to “strangers”, opening our homes, or simply engaging in heartfelt conversations with people we hardly know but with whom we share so much.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why living in Israel strengthens our family identity, but part of it may be that most Israelis are relatively recent immigrants. Very few can trace their presence in Israel beyond three or four generations. In place of the natural family history we left behind, we found ourselves forming a new, collective family identity in this land.

The war has intensified the already tangible sense of family in Israel, forcing us to live, grieve, and stand together as one extended household. We’ve operated beyond the usual boundaries of nationhood, helping one another and ensuring that families survive under the crushing strain of war.

Two years have passed, and even after a war for survival, we still haven’t found the recipe for national unity. Much of the strife revolves around the question of how democracy should be wielded. Can a slim majority impose its will upon the rest of society? How do we navigate opposing policies without descending into toxic discourse and corrosive dialogue? Ironically, democracy is pulling us apart from within.

Perhaps the path to unity begins with redefining our terminology. Perhaps we shouldn’t define Israeli society as a democracy. Democracy is merely the political system through which we conduct government and decide common policies. As the fairest form of governance, democracy should guide Israel, but our deeper identity must be that of a family, not merely a political system.

Family members have greater tolerance for one another and don’t focus solely on their own needs. They don’t impose solutions upon each other but instead seek to build consensus. Democracy is a contest; family is a compromise. The Pesach seder should instil in us a more acute sense of family, guiding us toward a softer discourse and a more tolerant and understanding vision of what it means to be a family living jointly in Israel.

- Moshe Taragin is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva. He has smicha and a Bachelor of Arts in computer science from Yeshiva University as well as a Master’s degree in English literature from the City University of New York.