Featured Item

Jewish doctor played a key role in miners’ silicosis settlement

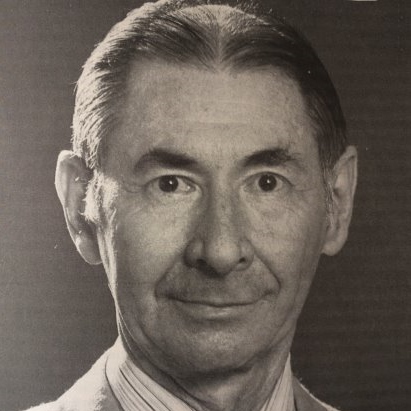

Pathologist and doctor Bertie Goldstein would have celebrated the fact that the Gauteng High Court finally approved a R5 billion settlement between miners and six large mining companies last Friday. It was a huge recognition of his life’s work as one of the earliest researchers into silicosis in miners in South Africa.

TALI FEINBERG

Goldstein, usually known as Bobby, passed away on 23 June in Johannesburg at the age of 94.

The agreement, on behalf of thousands of mineworkers and their dependents, affects people who contracted silicosis or pulmonary tuberculosis during or after being employed as gold miners from March 1965, according to Fin24.

According to the American Lung Association, “Silicosis is a lung disease caused by breathing in tiny bits of silica, a mineral that is part of sand, rock, and mineral ores such as quartz. It mostly affects workers exposed to silica dust in occupations such as mining, glass manufacturing, and foundry work. Over time, exposure to silica particles causes scarring in the lungs, which can harm your ability to breathe.”

“[Bobby] authored and co-authored a myriad papers on miners’ silicosis in South Africa,” says Eli Goldstein, his first cousin once removed. “The recent decision by the courts, which occurred a month after he passed away, would have been a culminating achievement for him in terms of his part in this saga as the hearings made use of academic findings.

“As a very humble man who was always loath to sing his own praises, I believe his work in the field of lung disease in South African miners went a long way toward the eventual settlement of R5 billion to mineworkers and their families this month.”

“He spent his working career conducting research into asbestosis in miners. My uncle is quoted as part of the team that ‘made valuable diagnostic and research contributions’ working with the Miners’ Medical Bureau and the SAIMR [South African Institute for Medical Research],” said associate professor Chyrisse Heine, the doctor’s niece, who thinks of her uncle like a second father. “He was part of a team that carried out about 2 500 routine heart and lung examinations a year for the bureau.

“He travelled all over the world, presenting his work at conferences and publishing his research, which is well-cited even today. One such citation is his work to demonstrate that coal miners have elevated risks of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, developing coronary obstructive pulmonary disease, deficits in ventilatory function, bronchitis symptoms, and silicosis.”

She says her uncle spoke four languages – English, Afrikaans, Zulu, and Yiddish. He started his medical career at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in 1943. An illness contracted in 1948 forced him to interrupt his studies for a few years, and he subsequently completed his medical degree in 1951.

Goldstein joined the SAIMR in Braamfontein in December 1955, where he worked in the unit dealing with pathology of the lungs and heart, and did research on the dust-related diseases contracted in asbestos coal and gold mines.

He was also later involved in research into occupational diseases, and this unit eventually became known as the National Centre for Occupational Health. He was admitted as a Fellow of the College of Pathologists in South Africa in 1966, and in 1967, during a long sabbatical, toured Europe, where he visited a number of medical laboratories that were doing similar work.

In subsequent years, Goldstein often attended and presented papers at local and international conferences dealing with dust-related diseases in miners. As a member of the South African Society of Pathologists, he was also affiliated to the International Society of Pathologists, and regularly attended and participated in their congresses.

Well-known for his work in lung pathology, Goldstein for many years demonstrated in practical sessions for undergraduate pathology students at the adjacent medical school. Later, when SAIMR and Wits Medical School amalgamated their pathology departments, he became a lecturer on the staff of the university’s medical school, where he gave an annual course of lectures on lung pathology to third-year students.

“Bobby officially retired at 63 in 1988, but continued to assist in and publish research work on a voluntary basis until he moved to the Rand Aid Elphin Lodge Retirement Village near Sandringham, Johannesburg,” says his cousin. “Besides his broad intellect, he was an amazingly curious person, always wanting to know more about subjects that were sometimes beyond his scope of focus on lung disease. He mastered the use of a computer at 87, and used it do research in various areas.

“One of his hobbies was photography. He left behind a huge collection of slides that he had taken in his lifetime on various trips locally and abroad while lecturing at conferences. He had a clear mind, and still drove his car up to two weeks before his death,” Goldstein says.

“Being the unassuming person he was, I doubt whether he would have wanted to be seen as the hero of the story, but I do believe he is owed immense recognition for the part he played in the large body of research used among other evidence to get the mining houses to settle.”

Beverley Price

August 1, 2019 at 3:50 pm

‘If you are reading this please see the documentary made by Catherine Myburgh and Richard Pakleppa "Dying for Gold" at any opportunity. During Jewellery Week in Johannesburg it will be screened in October. Otherwise be in touch with Catherine to arrange a screening.’